Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas took the opportunity Friday to again remind his fellow justices that it’s time to seriously rethink the doctrine of qualified immunity. The court denied certiorari in Hoggard v. Rhodes, leaving in place the Eighth Circuit’s ruling in favor of campus police who forced a college student to leave an area near a student union building.

Ashlyn Hoggard was a student at Arkansas State University who sought to set up a table near the facility to recruit new members for Turning Point USA, a conservative advocacy group founded by Charlie Kirk. Campus police forced Hoggard to remove her table because the designated “Free Expression Area” required advance permission from the school, which Hoggard did not have.

Hoggard brought a § 1983 lawsuit against the university, alleging that the school violated her First Amendment rights. Despite the rather obvious nature of the university’s free speech violation, the university prevailed at the summary judgment phase on the grounds that campus police were entitled to qualified immunity. Specifically, because there were no prior cases that “clearly established” Hoggard’s rights, campus police were immune from liability.

Justice Thomas, though, issued a statement disagreeing with the Court’s refusal to review the case, and calling on the Court to correct injustices created by continued use of the doctrine. Writing that qualified immunity is “on shaky ground,” Thomas centered his dissent around a pragmatic problem with its use.

A “one-size-fits-all doctrine is [] an odd fit for many cases,” remarked Thomas, who went on to argue that the same blanket protection against liability should not apply to law enforcement and to university staff.

As Law&Crime has discussed at length, qualified immunity is a judge-created concept that shields federal and state officials from liability. It requires a plaintiff to show that the right of which they were deprived is either specifically codified by statute or is otherwise “clearly established” by case law at the time of the incident. The doctrine, originally intended to put a manageable limit on post-Civil War lawsuits against police agencies in the South, has been often criticized in modern times for depriving victims of legal recourse even in grossly unfair contexts.

In her petition for certiorari, Hoggard urged SCOTUS to use her case to resolve the mess that has become of qualified immunity jurisprudence.

“The quagmire of lower-court, qualified-immunity rules—particularly on public-university campuses—is in desperate need of this Court’s clarification,” Hoggard’s legal team wrote. “Review is warranted.”

Likely, Hoggard’s lawyers expected a receptive audience in Justice Thomas. In recent cases, Thomas has repeatedly raised concerns about the doctrine of qualified immunity as a general matter.

Although much of the public criticism about qualified immunity has centered around unfairness resulting in cases of excessive force by police, Hoggard v. Rhodes presented the justices an opportunity to reconsider the concept outside the context of police work.

Thomas’s statement highlighted the need for the Court to reconsider the doctrine in light of the practical differences between law enforcement and other public work. He wrote:

But why should university officers, who have time to make calculated choices about enacting or enforcing unconstitutional policies, receive the same protection as a police officer who makes a split-second decision to use force in a dangerous setting? We have never offered a satisfactory explanation to this question.

Qualified immunity is a topic which carries the rare potential to unite Clarence Thomas with more left-leaning individuals. However, as attorney Hannah Mullen pointed out, no other justices joined Thomas’ statement, leaving open the question of where the judges stand on qualified immunity in cases not involving excessive force.

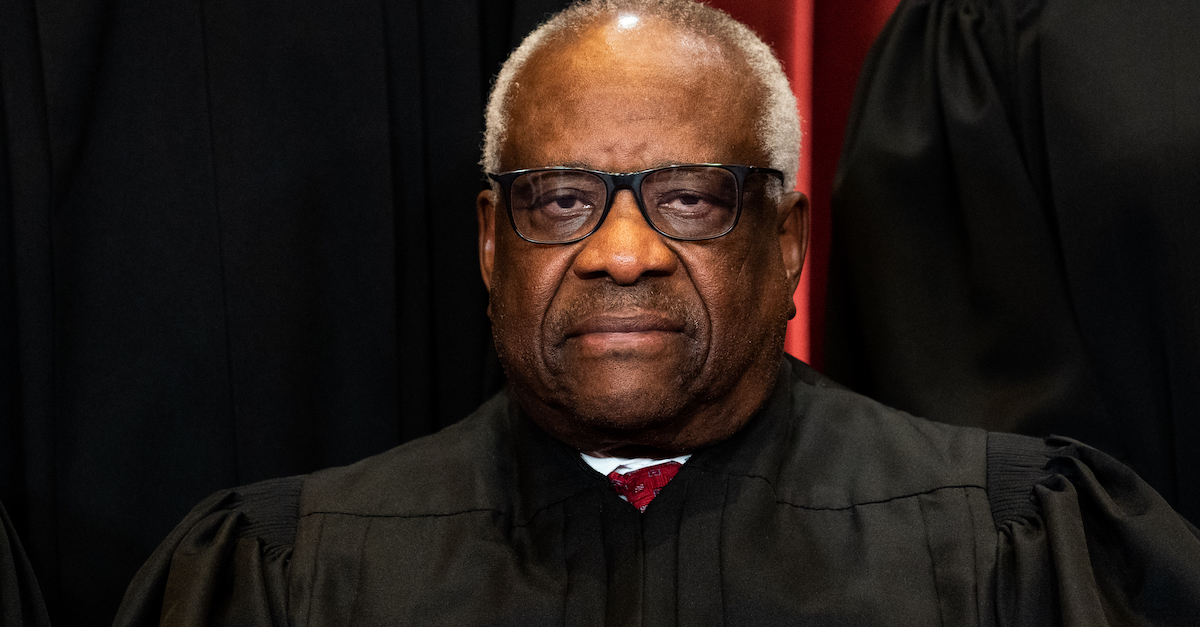

[image via Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images]