Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett, on day two of the Senate Judiciary Committee hearings, was asked some direct questions about important topics and she gave some non-answers, in her view, also for important reasons. The bottom line is that Barrett declined to answer whether she agreed with her former boss Antonin Scalia that Roe v. Wade was wrongly decided; and Barrett declined to say, one way or another, whether she would recuse herself from cases related to Obamacare. Barrett will inevitably be asked the same question about recusing herself from election cases—as liberals style her rushed appointment to the Supreme Court as a last-ditch, desperate effort from a president behind in the polls and looking to seal the deal on yet another quid pro quo. What Barrett did say is that she isn’t a theocrat.

Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) kicked off the questioning by drawing a distinction between Brown v. Board of Education and Roe v. Wade. In the former case, the Supreme Court unanimously rejected and overturned the “separate but equal” doctrine that enabled racial segregation. Graham said no one would seriously consider attempting to reinstitute segregation through the courts. Unlike Brown v. Board of Education, “abortion on demand” is and has been challenged by state and local governments, Graham said. Barrett herself has discussed in her scholarship the differences in the apparent strength of precedents.

One key difference was the idea that because there are challenges of a given case there is still a live controversy. For Barrett, there is a controversy in Roe and Planned Parenthood v. Casey that doesn’t exist in Brown v. Board of Education.

Graham got t0 the point, asking Barrett whether she would be able to set her Catholic beliefs aside if or when she would hear an abortion-related case.

“I can. I have done that on my time on the Seventh Circuit,” Barrett answered, saying that a judge does not simply wake up one day and overturn a precedent she does not like.

Later, Ranking Member Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) asked if Barrett agreed with Scalia (for whom Barrett once clerked) that Roe was wrongly decided. Barrett dodged that by appealing to something Justice Elena Kagan during her confirmation hearings. Barrett said it would be a “violation of the canons to me to [answer] that as a sitting judge.”

Sen. Graham also asked Barrett about the issue of recusal.

Barrett was asked if she thinks that she should recuse herself from deciding a case currently on the Supreme Court’s docket: whether Obamacare will stand without the individual mandate or whether the Trump administration’s effort to eliminate the healthcare law entirely. Barrett, in her time as a law professor, commented publicly in the past on other Obamacare cases. Barrett did not definitely answer the question about recusal as it pertained to Obamacare, and we can presume that her response would be the same with any issue—including election-related cases.

Barrett said that “recusal itself is a legal issue” and cited to 28 USC § 455. That statute simply says that “[a]ny justice, judge, or magistrate judge of the United States shall disqualify himself in any proceeding in which his impartiality might reasonably be questioned.”

The question of recusal, Barrett said, is “not a question I can answer in the abstract.”

“You’ll do what the Supreme Court requires of every justice?” Graham asked.

“I will,” Barrett replied.

The truth is as simple as this: Barrett can recuse herself is she wants to or not. It needn’t be any more complicated than that.

Some legal ethics experts believe Barrett should not decide a potential case of crucial importance to President Donald Trump’s reelection; others believe Barrett has a “duty” to participate fully despite the circumstances of her appointment.

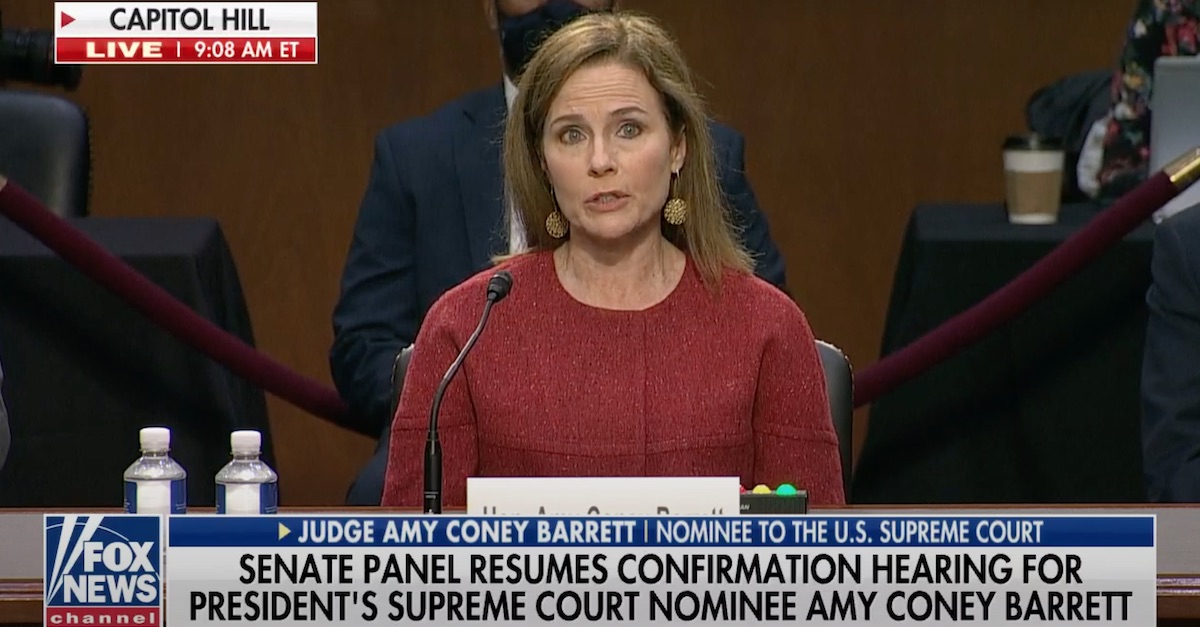

[Image via Fox News screengrab]