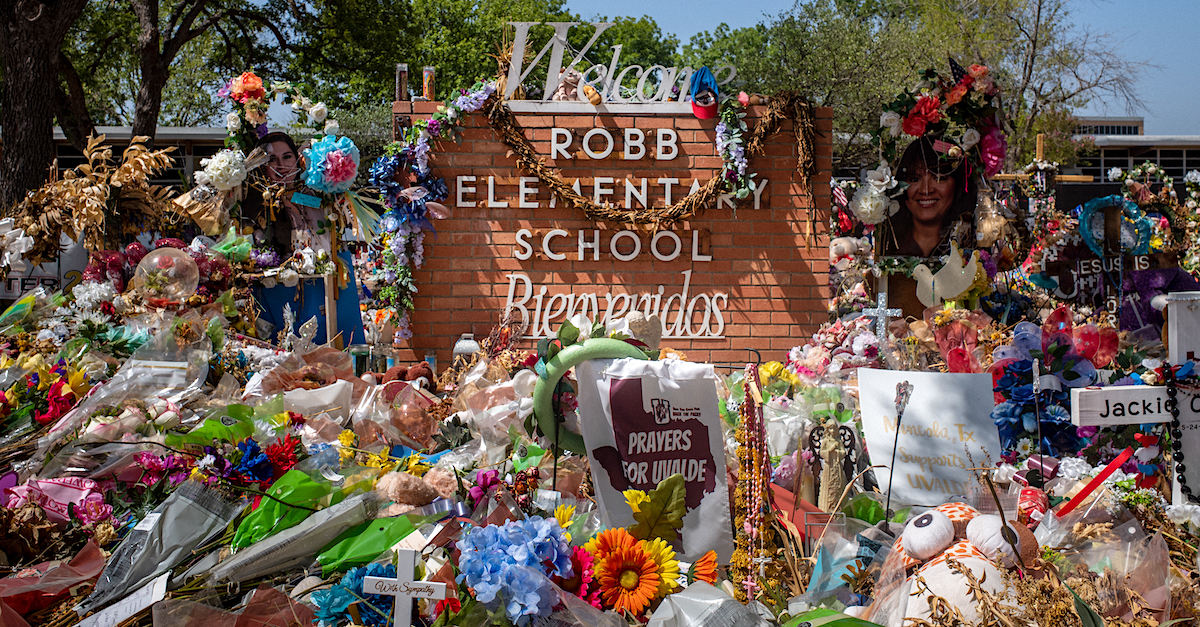

The Robb Elementary School sign is seen covered in flowers and gifts on June 17, 2022 in Uvalde, Texas. (Photo by Brandon Bell/Getty Images.)

At a Tuesday hearing, the Director of the Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) established a harrowing timeline for the law enforcement response to the school shooting in Uvalde that claimed the lives 19 children and two teachers on May 24.

DPS Director Steven McCraw testified before the Senate Special Committee to Protect All Texans that the police response to the massacre was an “abject failure and antithetical to everything we have learned over the past two decades.”

“Within three minutes of the shooter entering the building, nine officers were in the school with pistols and rifles, and the classroom doors to classroom[s] 111 and 112 were unlocked,” remarked Sen. Brandon Creighton (R-Dist. 4) in a recap of the committee’s many recent factual discoveries. “Within five minutes of the shooter entering the building, Chief [Pete] Arredondo is saying he doesn’t have the necessary resources to advance on the shooter.”

Arredondo, the school district’s police chief, was scheduled to appear during a separate closed-door hearing before the House of Representatives on Tuesday. In Texas, school districts are allowed to have their own police departments, which are separate and distinct from municipal, county, and state law enforcement agencies.

The state’s narrative conflicted with previous versions of the events which suggested the classroom in which the shooter was located was locked.

“I don’t believe based on the information we have right now that door was ever secured,” McCraw said.

The DPS point-man said the shooter “didn’t have a key” and “couldn’t lock it [the door] from the inside.”

Indeed, there was “no indication officers tried to open the door while the gunman was inside,” Dallas NBC station KXAS said in a summer of McCraw’s testimony. Still, “police waited around for a key.” The New York Times also reported that it was “not apparent” in school surveillance videos “that anyone had checked the classroom door to see if it was locked.”

The latter appears to be a reference to comments by Arredondo earlier in June. He said he assumed he was dealing with a hostage crisis and waited for keys to be provided to him to enter the room. In an interview with the Texas Tribune, Arredondo generally dismissed claims that he stalled on his response.

“The only thing that was important to me at this time was to save as many teachers and children as possible,” Arredondo said in a report published by the Tribune on June 9.

“Not a single responding officer ever hesitated, even for a moment, to put themselves at risk to save the children,” Arredondo continued, again per the report. “We responded to the information that we had and had to adjust to whatever we faced. Our objective was to save as many lives as we could, and the extraction of the students from the classrooms by all that were involved saved over 500 of our Uvalde students and teachers before we gained access to the shooter and eliminated the threat.”

McCraw’s testimony as a whole disagreed with Arredondo’s assessment of the situation.

Steve McCraw testifies on Tuesday, June 21, 2022. (Image via YouTube screengrab.)

The first law enforcement officer with a protective shield arrived at the school at 11:52 a.m., McCraw’s testimony revealed. That was 19 minutes after Ramos entered the classroom, and yet it took the assembled forces waited “one hour, 14 minutes, and eight seconds” to enter the classroom and kill mass murderer Salvador Ramos, McCraw told the legislative committee on Tuesday.

During that delay, students remained inside the room calling 911 and pleading for a police rescue.

“You don’t wait for a SWAT team,” McCraw said while generally lambasting the response of the local constabulary. “You have one officer, that’s enough.”

McCraw said those on the scene “decided to put the lives of officers ahead of the lives of children.” He also said the commander on the scene “waited for a key that was never needed.”

Elsewhere, McCraw called the delay “intolerable” and said it “set our profession back a decade.”

Arredondo didn’t have a police radio. Some of the officers who did have radios found that they didn’t work well inside the school.

During the hearing, Royce West, a Democrat, asked McCraw about limiting certain gun purchases to individuals under 21. He questioned whether people under 21 were “mature enough” to “operate high-caliber weapons.”

“I think it has less to do with maturity and more to do with about mental capacity, and there are certain people — they may be immature, but they’re not evil,” McCraw said.

McCraw generally demurred on questions which might have suggested various policy changes and said suggested such issues should remain with the legislature.

Watch the testimony below: