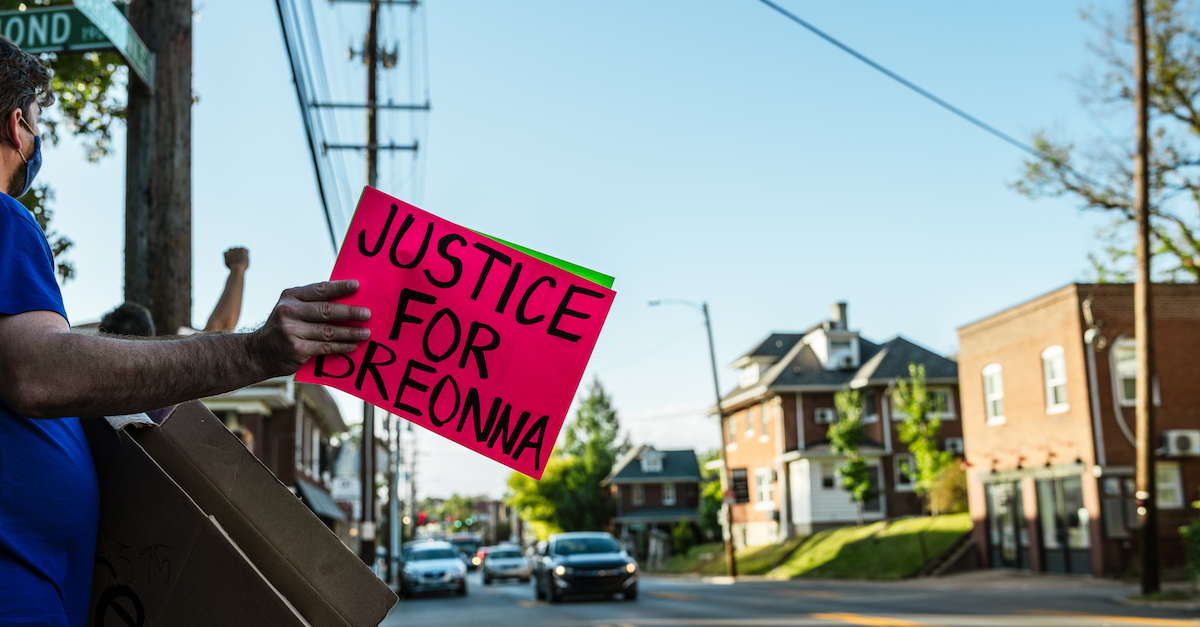

Protesters with signs display them to passing cars the sidewalk on September 30, 2020 in Louisville, Kentucky. The demonstration was organized by local parents and teachers in the Highlands neighborhood to protest the March 13th killing of Breonna Taylor by police during a no-knock warrant at her apartment.

The dust has begun to settle.

It is now totally clear: Breonna Taylor, a totally innocent Black woman, died a senseless death. Louisville Kentucky police mistakenly raided her apartment in search of drugs and shot 6 bullets into her–after firing 32 bullets–thereby killing her. Who, particularly those in her community, wouldn’t think that the police officers should be indicted for her death? And who wouldn’t question the integrity of a secret investigation that largely let the police off the hook?

* * *

Transparency and due process for those under investigation are diametrically competing values–but especially when the time-honored protocol of grand jury secrecy is implicated. Grand jury investigations have, indeed, always been conducted under wraps largely to protect those who are investigated but are never charged because the evidence against them is insufficient or even non-existent. After all, if an accusation turns out to be weak, legally insufficient or maybe even false, why should the accused be subjected to a public obloquy that simply isn’t deserved or warranted?

In most cases, no one challenges this time-honored tradition. Yes, if a defendant is charged, the defendant and his counsel (but not the public) do obtain the witness grand jury statements, often even if the witness doesn’t testify at trial (likely, when his testimony helps exculpate the defendant). Basically, though, it typically all comes out in the wash at trial.

The real “societal” problem regarding grand jury secrecy becomes noteworthy and pronounced, however, when a public figure isn’t indicted and there is a public outcry that he should have been–and, indeed, should still be. Where does this typically arise? Virtually every time it is when there has been police conduct, typically misconduct, that has resulted in a Black individual dying but yet no criminal indictment charging that death is brought by a grand jury – e.g., Michael Brown (Ferguson, Missouri); Eric Garner (Staten Island, New York); and, most newsworthy recently, Breonna Taylor (Louisville, Kentucky).

In each of these instances, members of the community and others concerned about police behavior, or even anonymous sitting grand jurors (as in the Taylor presentation) have demanded release of the entire grand jury record so that the “public” can assess the legitimacy of the presentation. Or, put differently, the public sentiment erupts to challenge either a conscious or unconscious “dive” by the prosecutors in favor of police officers with whom the prosecution office must necessarily interact daily. Remember Judge Sol Wachtler’s famous statement: “a grand jury would indict a ham sandwich” if the prosecutor wanted it to? Why then, can’t prosecutors seem able to indict police officers?

Sometimes, the public face of the police killing is so troubling, like when a chokehold literally killed Eric Garner while a videotape recorded the event, that it is hard to persuade the public that the police didn’t criminally kill the suspect. Some argue that only making public the entire grand jury record can possibly persuade the public that a criminal charge wasn’t warranted (being terminated by the police force being a different question).

Now, traditionalists will argue that grand jury secrecy means grand jury secrecy—period. Once the system allows an “exception” given a hue and cry by the public after which the camel is allowed to stick its nose under the tent, the system risks wholesale rulings by judges determining that the public’s right to know outweighs the need for jury secrecy. It also risks, as in Breonna Taylor’s case, a judge’s willingness to rule that jurors themselves–even an anonymous juror who believed there was enough evidence to indict when the experienced prosecutors thought otherwise–had the right to demand a public disclosure of the grand jury record by publicly commenting on it. Yes, the Kentucky judge who ruled in favor the of juror was able to say that the vast majority of the record was already public anyway, so why not release the rest? Still, doesn’t it set a potentially dangerous precedent?

* * *

As a former state and federal prosecutor I see great value in a grand jury secrecy that prohibits both prosecutors and jurors from disclosing what occurred behind closed doors. I also see value in occasionally assuring the public that things didn’t go awry behind those same doors. The problem, though, is that most of the public will not read a transcript of grand jury proceedings–they often consist of hundreds, even thousands of pages, and contain reams of procedural and administrative gobbledygook. And if the public relies on journalists to tell them what is in the transcript … we all know it will not be interpreted the same way, maybe even skewed, for example, by the New York Post and New York Times.

Why, when a question arises about a particular grand jury presentation, can’t a judge who supervises the grand jury confidentially review the entire record as the public’s surrogate and publicly report, if applicable, that the presentation was fair, and the available evidence was indeed insufficient to indict? Or, the judge can confidentially question the prosecutor in determining whether the presentation was fair. And, if the judge determines it was not, only then order a release of the transcript in the public interest. Judges make weighty decisions like this all the time after an indictment is actually filed. Why can’t they do the same thing here when an indictment isn’t brought, particularly when the public, or even when grand jurors (as in Louisville), suspect the prosecutor’s motives or ability?

Clearly, the skepticism over secret grand jury presentations when police kill suspects or detainees is totally understandable. The public has good reason to be skeptical. That skepticism, however, shouldn’t enable the public to essentially make, or even challenge, prosecutorial decisions–and, to some extent, releasing grand jury testimony enables the public to second—guess prosecutors when independent judges are available to make such decisions.

There are necessarily exceptions. Nonetheless, grand jurors, however well motivated and especially when they don’t put their names on the line to protest what they perceive as an injustice, aren’t in the most reliable position to assess for the public whether an indictment should or should not have been brought.

Breonna Taylor died a horrible death, and needlessly. Still, the justice system should employ judges, not grand jurors nor journalists who editorially report on what they read in grand jury transcripts, to decide for the public if the police–or others who survived a grand jury investigation for a person’s death—got away with murder, either literally or figuratively.

The entire regime of grand jury secrecy may indeed warrant rethinking. But until then, the courts need to be careful when creating exceptions.

Joel Cohen practices white collar criminal defense law as senior counsel at Stroock & Stroock & Lavan in New York. He is the author of “I Swear: The Meaning Of An Oath” (Vandeplas Publishing, 2019) and is an adjunct professor at both Fordham and Cardozo Law Schools.

[Image of Jon Cherry/Getty Images]