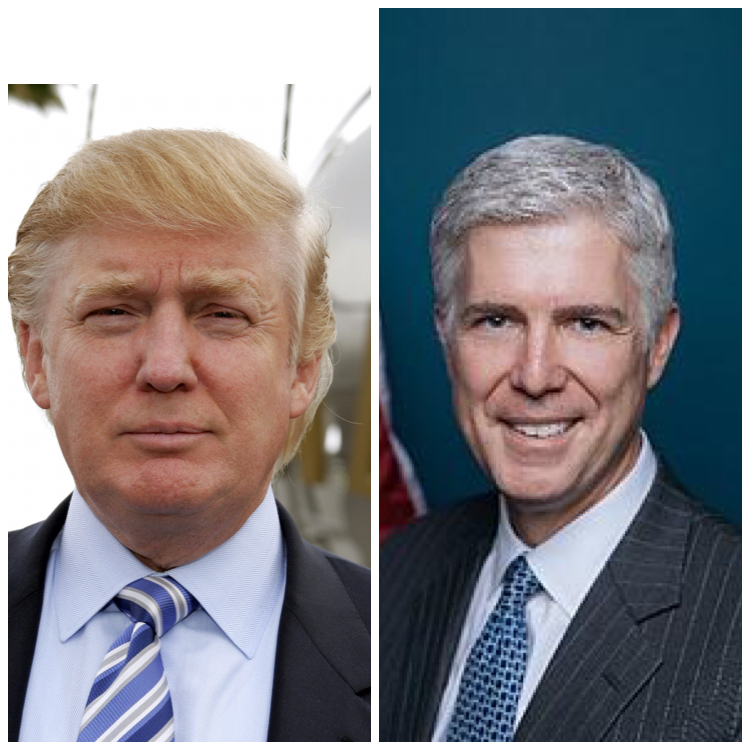

Justice Neil Gorsuch would likely call Trump’s Syria strikes unconstitutional. Gorsuch follows the originalist interpretation of the Constitution. The originalist interpretation relies upon what the people thought at the time of the passing of the Constitutional provision at issue. This reflects a democratic impulse in law: that judges should apply the law, not create it, and defer to the judgment of the people who passed it at the time it was passed. If the people want something different, then the means of remedy is amendment by the people, not reinterpretation by unelected jurists. It also means eschewing results-oriented judging, even if the effect of a ruling hurts one’s own party or goes against the preferred outcome for a person or political interest involved in the case. (Gorsuch was criticized as “heartless” for this reason; his originalist philosophy allows undesirable outcomes on people when that outcome is compelled by an originalist understanding of the text and history. In his defense, advocates of originalism view both the law, and the democratic nature of our government, as judges looking to the law, not to the desired effect of a decision, as the basis for being a true, and honest, jurist. For them, the law is not a place for Platonic Guardians overseeing the Republic, but a place for Constitutional Guardians giving meaning to the democratic desires of the public, as reflected in the Constitution’s text and history at the time the public passed it into law).

Justice Neil Gorsuch would likely call Trump’s Syria strikes unconstitutional. Gorsuch follows the originalist interpretation of the Constitution. The originalist interpretation relies upon what the people thought at the time of the passing of the Constitutional provision at issue. This reflects a democratic impulse in law: that judges should apply the law, not create it, and defer to the judgment of the people who passed it at the time it was passed. If the people want something different, then the means of remedy is amendment by the people, not reinterpretation by unelected jurists. It also means eschewing results-oriented judging, even if the effect of a ruling hurts one’s own party or goes against the preferred outcome for a person or political interest involved in the case. (Gorsuch was criticized as “heartless” for this reason; his originalist philosophy allows undesirable outcomes on people when that outcome is compelled by an originalist understanding of the text and history. In his defense, advocates of originalism view both the law, and the democratic nature of our government, as judges looking to the law, not to the desired effect of a decision, as the basis for being a true, and honest, jurist. For them, the law is not a place for Platonic Guardians overseeing the Republic, but a place for Constitutional Guardians giving meaning to the democratic desires of the public, as reflected in the Constitution’s text and history at the time the public passed it into law).

The President must get Congressional approval before attacking Syria-big mistake if he does not!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 30, 2013

What does an originalist interpretation of the Constitution say about American-initiated military action overseas? From an originalist perspective, the strongest evidence, both from the text itself, and from the historic understanding of the terms in the text at the time of its passage, restrict Presidential use of military power overseas to limited circumstances not met by the Syrian strikes.

First, the Constitution.

Article I of the Constitution vests Congress alone with the decision to “declare war.” Reflective of that power, Article I further exclusively vests Congress with related powers: the power to “raise” an army; the power to “support” an army; the power to “provide” a navy; the power to “maintain” a navy”; the power to seize foreign vessels (called “letters of marque”); the power to seize foreign goods (“reprisal” in the text); the power to make all navigation rules concerning the high seas; the power to “regulate commerce with foreign nations”; the power to “punish” violations of international law; the power to call forth “the militia”; the power to control the spending of monies when “for the common defense”; and all powers of law-making “necessary” to execute those Constitutional powers.

By contrast, Article II treats the President as the executor of wars, not the initiator of wars, more akin to a general’s power. The Constitution gives no power to the President to “declare war,” “raise an army,” or “punish” violations of international law. Instead, the Constitution limits the President to playing the role of “commander in chief of the Army and Navy and militia” only “when called into the actual service of the United States.” Note that provision: the President is not always the “commander in chief” under the Constitution; the President is only the commander in chief “when [the military is] called into the actual service of the United States.” The Constitution assumed the army, navy and militia would not be constantly, continuously, and completely called into “actual service” at all times. Otherwise, the President’s power is limited to taking care that the laws be “faithfully executed,” with the “executive power” needed therefore to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.”

Second, the history.

At the time of the founding, according to the leading legal scholars and historians, and under the originalist interpretation of admissible evidence for assessing founding’ intent, “declaring war” meant initiating any form of hostility by any form of proclamation or attack. In this historical context, the Syrian strikes constitute a declaration of “war.” It is this historical context Gorsuch considers paramount in constructing the Constitution. Notably, the originalist view carves out an exception for emergency defense actions. The Syrian strike, though, would not meet the historic definition of such an emergency defense action, as it initiated action to, in the words of the President and his team, “punish” and “send a message” to Syria. Equally, Trump and Tillerson both cited the Treaty on Chemical Weapons as their legal basis for their course of conduct. Aside from the fact that treaty is not self-enforcing and affords no authorization for immediate, imminent military action, enforcing such a treaty is precisely the kind of “punishing” for violations of international law that the Constitution gave to Congress. This is precisely the kind of “initiation” of military conflict and military action the Constitution exclusively gave to the legislative branches. Why did the Constitution do so?

According to legal historians, the reason was fear of one man making all the decisions of life and death when it came to war. The leading intellectual lights of our founding fathers each demanded Congress alone control the initiation of military action: George Washington (our first “commander in chief”); John Adams (our second commander in chief); Thomas Jefferson (our third commander in chief); and a litany of leaders, future Presidents, and founding advocates amongst them. Historians have been unable to locate a single instance in which a prominent member of the Founders believed the President could Constitutionally initiate a war. The reason for this unanimity? The Founders arose in an era of kings, and they witnessed the horrors war visited upon the populace in the era of kings. They were thus determined no one man would ever hold such power again in America.

A popular meme amongst Trump’s youthful reddit supporters celebrates Trump as “Emperor Trump.” For originalists, the Constitution sought to end emperors, nor empower them. On the Syrian strikes, as an originalist, Gorsuch would agree with the Founders, and not Trump.

Robert Barnes is a California-based trial attorney whose practice focuses on Constitutional, criminal and civil rights law. You can follow him at @Barnes_Law

This is an opinion piece. The views expressed in this article are those of just the author.