California’s Democratic Attorney General Xavier Becerra filed a motion in a case over the “decency” standard for vanity license plates. In it, Becerra’s argument about how the First Amendment works was shockingly incorrect.

The underlying lawsuit was filed by five plaintiffs, all of whom sought personalized license plates from the California Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV). The DMV denied plaintiffs’ requests on the grounds that their requested plates would have contained configurations that are “offensive to good taste and decency” under the relevant California law.

Here were the plates the plaintiffs requested:

“OGWOOLF,” sought by Army veteran Paul “Chris” Ogilvie of Concord, California. Ogilvie says the plate is a tribute to his military nickname, while the DMV said people might misinterpret “OG” as meaning “original gangster.”“DUK N A,” requested by Andrea Campanile, who says it’s an abbreviation for “Andrea” and “Ducati motorcycles,” but which the DMV says sounds like an obscene phrase.

“BO11UX,” meaning “bullocks” as a synonym for “nonsense,” sought by Paul Crawford, a British immigrant whose pub has the motto “real beer, proper food, no bollucks.” The DMV rejected it for having “a discernible sexual connotation or may be construed to be of sexual nature.”

“SLAAYRR,” after the heavy metal band. The DMV rejected it for being “threatening, aggressive or hostile.”

“QUEER,” requested by Amrit Kohli, a gay folk musician with Queer Folks Records. Kohli has argued that he asked for the license plate as part of an ongoing attempt to reclaim what has become a pejorative label. The DMV rejected it for being “insulting, degrading or expressing contempt for a specific group or person.”

U.S. District Judge Jon Tigar, a Barack Obama appointee, denied California’s motion to dismiss last July, finding that California’s statute was sufficiently problematic on its face as to allow the case to continue. California had tried to convince the court that license plates count as “government speech”—and are, therefore, not subject to First Amendment protection. Tigar instead ruled, relying on the holding in Supreme Court decision in Matal v. Tam, that government approval of a trademark does not mean the mark is owned by the government.

Whatever one feels about the limits of proper vanity plates, though, what was really problematic was Becerra’s misstatement of First Amendment law.

As Reason‘s Eugene Volokh pointed out, Becerra included this statement in his pleading:

“There are well-defined and narrowly-limited classes of speech, ‘the prevention and punishment of which have never been thought to raise any Constitutional problem.’ Chaplinsky v. N.H., 315 U.S. 568, 571-572 (1942) (emphasizing that certain types of speech are protected by the First Amendment). Obscenity, vulgarity, profanity, hate speech, and fighting words fall outside the scope of the First Amendment’s protections.”

But Becerra is dead wrong on the issue of “hate speech.”

The First Amendment does protect individual speech; like other rights, free speech is not absolute. Over the years, the Supreme Court has carved out categories of speech that are “unprotected” by the First Amendment—categories that can legally be regulated or prohibited with offending the Constitution. Becerra is right that obscenity and fighting words are two such categories (defamation, and perjury are two more). “Vulgarity” and “profanity” are not categories on their own, but rather, can fall under of “obscenity” if they rise to the legal level.

“Hate speech” is not a legal designation, but rather, a conversational term. Usually, “hate speech” is meant to characterize speech that is overtly offensive, inflammatory, and derogatory. Racist, sexist, homophobic, anti-Semitic slurs are often labeled “hate speech.” The term is useful when generalizing about blatantly offensive speech aimed at a particular person or group.

The term does not have independent legal import, however. SCOTUS has never ruled that “hate speech” constitutes a new category of unprotected (and therefore, regulable) speech. Some “hate speech” is obscene, and some incites violence; on those bases, such speech would be denied First Amendment protection. On its own, though, the fact that speech is hateful does not render it outside the realm of constitutional protection.

While many legal principles have been the subject of erosion courtesy of SCOTUS, this one isn’t budging. In a 2019 opinion, Justice Elena Kagan wrote that the First Amendment “does not allow the government to penalize views just because many people, whether rightly or wrongly, see them as offensive.”

“The most fundamental principle of free speech law is that the government can’t penalize or disfavor or discriminate against expression based on the ideas or viewpoints it conveys,” she continued.

Kagan’s comments echoed Justice Samuel Alito‘s 2017 opinion in Matal v. Tam, in which he wrote that any suggestion that the government can restrict “speech expressing ideas that offend” would “strike[] at the heart of the First Amendment.”

“Speech that demeans on the basis of race, ethnicity, gender, religion, age, disability, or any other similar ground is hateful; but the proudest boast of our free speech jurisprudence is that we protect the freedom to express ‘the thought that we hate,'” Alito continued.

It’s not often that the Supreme Court is so clear or so united on an issue. Hate speech, however, is one of the rare topics on which the justices (at least in a basic sense) agree. The non-judicial world, however, is often confused about the difference between “hate speech” as a stand-alone legal category and hateful rhetoric that incites imminent violence. Legal experts, including my colleague Aaron Keller, have mercilessly pointed out the woeful inaccuracy of the New York Times’s misstatement of hate speech rules.

Still, one would expect the Attorney General of California to get it right. Even though little more than license plates are at stake in this particular case, free speech continues to be an issue of growing national concern.

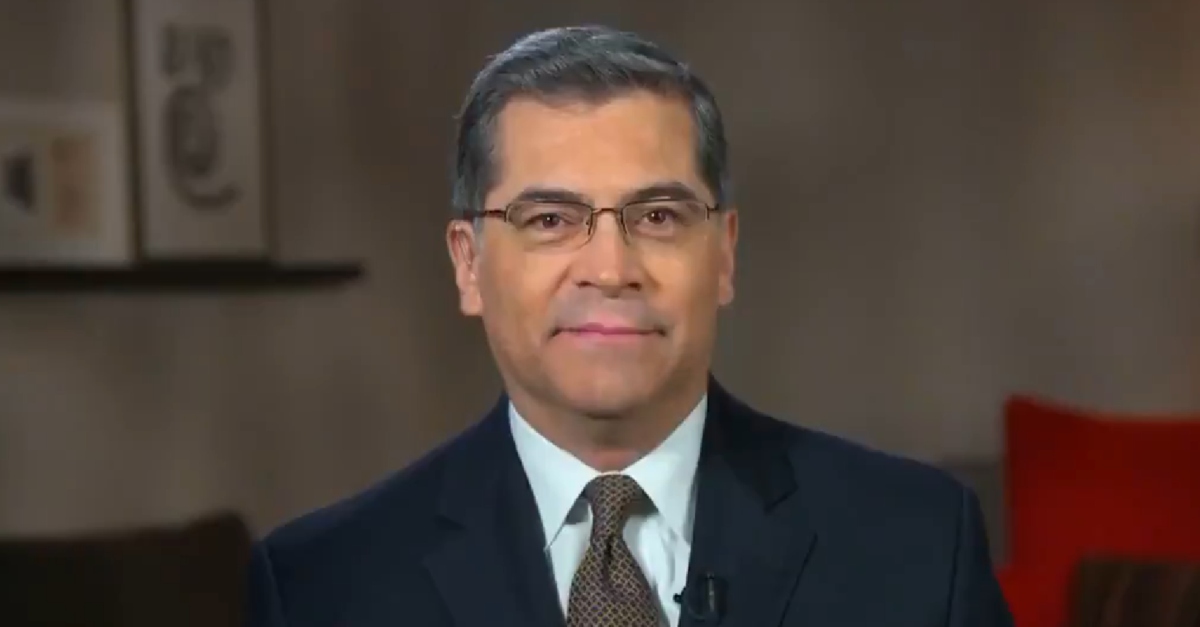

[image via ABC screengrab]