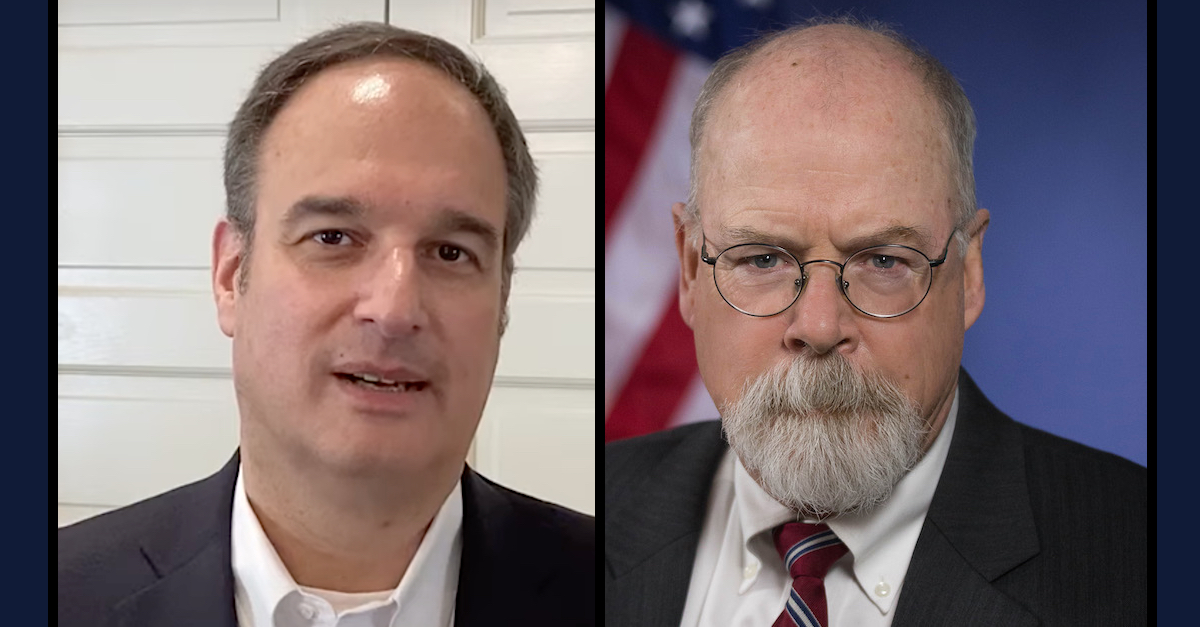

Michael Sussmann and John Durham.

Listen to the show on Apple Podcast, Spotify or wherever else you get your podcasts, and subscribe.

After special prosecutor John Durham filed a document claiming that a tech executive “exploited” internet traffic data to find derogatory information about Donald Trump, the allegation instantly set off a furor on the political right.

“The most striking example I recall hearing was Jesse Watters on Fox saying that Durham had disclosed that Hillary Clinton paid people to hack into Donald Trump’s home and office computers in order to plant evidence of Russian collusion,” the Cato Institute’s senior fellow Julian Sanchez recalled on the latest episode of Law&Crime’s podcast “Objections: with Adam Klasfeld.”

Describing Watters’s assertion as “impressive” in its falsehood, Sanchez added: “Literally no part of that sentence is correct.”

“Supposed to Be a Kind of Scandal Bigger Than Watergate”

That Fox News talking head was hardly alone. According to CNN’s Brian Stelter, Fox invoked Durham’s name more than 600 times on the week the document was filed. Other media outlets on the political right, like the Washington Examiner, the Federalist and Breitbart, followed suit.

“This was supposed to be a kind of scandal bigger than Watergate, and we’ve sort of stopped hearing about it,” Sanchez noted.

Fox’s interest in the scandal quickly dried up after Clinton remarked that the network was getting “awfully close to actual malice,” a remark widely interpreted as hinting at a possible defamation suit. The would-be scandal also dissipated after Durham himself distanced himself from the public fallout, disclaiming responsibility if “members of the media have overstated, understated, or otherwise misinterpreted” what this prosecutors wrote.

Specializing in issues of privacy, technology and civil liberties, Sanchez says that there was an actual story buried beneath the heap of overheated rhetoric, and as he recently laid out in a viral Twitter thread, it is about a thorny problem of privacy in an age of bulk data analysis.

Durham, the special prosecutor tapped by ex-Attorney General Bill Barr to look into the origins of the Russia investigation, has been prosecuting Democratic Party-tied lawyer Michael Sussmann for allegedly lying to the FBI. Sussmann had told authorities about a “secret communications channel” between the Trump campaign and Alfa Bank, a now-sanctioned Russian bank.

There is no allegation that this tip was a lie, but Durham alleges that Sussmann misled authorities by claiming that he was passing on the information as a good citizen, not as a representative of the Clinton campaign.

“The implication Durham is painting here is there seems to be some kind of shady motive here, or maybe there was some political motive,” Sanchez noted.

Sussmann’s lawyers recently moved to dismiss the indictment as an “unprecedented,” “unjust” and “unlawful” prosecution of an “innocent man.” They say that they have found “no case in which an individual has provided a tip to the government and been charged with making a false statement for something other than providing a false tip.”

“Not Super-Well-Protected”

According to Durham, a tech executive—reported to be cybersecurity researcher Rodney Joffe—was working for the Neustar, which had a contract with the Executive Office of the Presidency and was one of Sussmann’s clients.

In July 2016, Joffe worked with researchers, reportedly from the Georgia Institute of Technology, to analyze DNS records and identify possible security breaches. Those records do not include the content of internet traffic, but they do illuminate when one computer is looking for the address of another. Detecting patterns he found unusual, Joffe reportedly passed on the findings with Sussmann, who shared two sets of tips with the FBI and the CIA.

“So one had to do with this suspicious-to-the-researchers traffic between servers at Trump Tower—actually servers probably owned and run by another organization that’s been providing spam marketing mail services to the Trump Organization,” Sanchez noted. “And then a second tip to the CIA concerning the […] apparent presence of rather rare Russian-made cell phones near, among other places, Trump Tower and the and the White House executive offices, as revealed by DNS records.”

Durham has not accused Sussmann with any violations of privacy law, nor has he accused Joffe of any wrongdoing. Sanchez noted that Durham let the statute of limitations expire over such claims, and it is undisputed that Neustar had lawful access to the data.

The New York Times, which reported what the researchers found months before the Durham filing, noted that the data came from the tenure of Barack Obama’s administration.

Underneath the supposed geopolitical intrigue, Sanchez notes that there’s a less dramatic story to be told about the ready availability of large data sets of DNS records by private actors, who can in turn pass that information on to law enforcement.

“DNS records are, as it stands, not especially—if they’re not encrypted—not super-private, not super-well-protected,” Sanchez said.

Though these records may be mined commonly, Sanchez asked: “Look, if I asked you, do you think a list of every website you visit in the course of a day from your home, your phone [to the] internet is public information? Can anyone just go online and look up what websites have you been visiting? I think you would probably say ‘No,’ and I think, rightly, that is not information generally, typically public. Would you perhaps be unhappy if such a list were published? I think for most people, the answer is probably, ‘Yes.'”

“An Interesting Policy Issue”

Due to federal restrictions governing information-sharing with law enforcement, Sanchez noted that it is also “quite common” for tech companies to provide such data through an intermediary like a lawyer, and Capitol Hill is starting to take note of it.

“One effort to try and change this somewhat is Ron Wyden’s Fourth Amendment Is Not for Sale Act, which essentially would would say, ‘Look, the government can no longer obtain by purchase various kinds of telecommunications metadata for which they are otherwise would be required to go and obtain judicial process and also closes this sort of foreign intelligence loophole,’” Sanchez said.

Once memorably described as “the internet’s senator,” Sen. Wyden (D-Ore.) is now the chair of the Senate Finance Committee, and he’s a privacy hawk who has been a prominent critic of bulk metadata collection. The problem, however, is thorny and has received push-back from intelligence services.

“The argument I hear from intelligence people—that I’m not wholly persuaded by, but I understand the perspective here—is, ‘Look, if you have a scenario where this information is being sufficiently widely shared, that reliably, for example, hostile governments may be able to access it, and overseas companies that can be made to turn it over by hostile regimes can access it,” Sanchez noted. “There’s a point at which, is it really rational to say, you know, of all entities on Earth, the U.S. government is uniquely forbidden from accessing this type of information?”

Sanchez, who is a fellow at a libertarian think tank, is ultimately skeptical of this argument, but he believes the challenge should be addressed.

“So that’s why I think there is an interesting policy issue here and interesting tech, policy and privacy issue here,” he said. “It’s just clearly not the issue that that we were getting on Fox, which is, ‘This is a story about spying at the behest of Hillary Clinton, unrivaled in the annals of American history since since the days of Watergate.'”

Listen to the episode, below:

[photo of Sussmann via YouTube screengrab; photo of Durham via U.S. Department of Justice portrait]