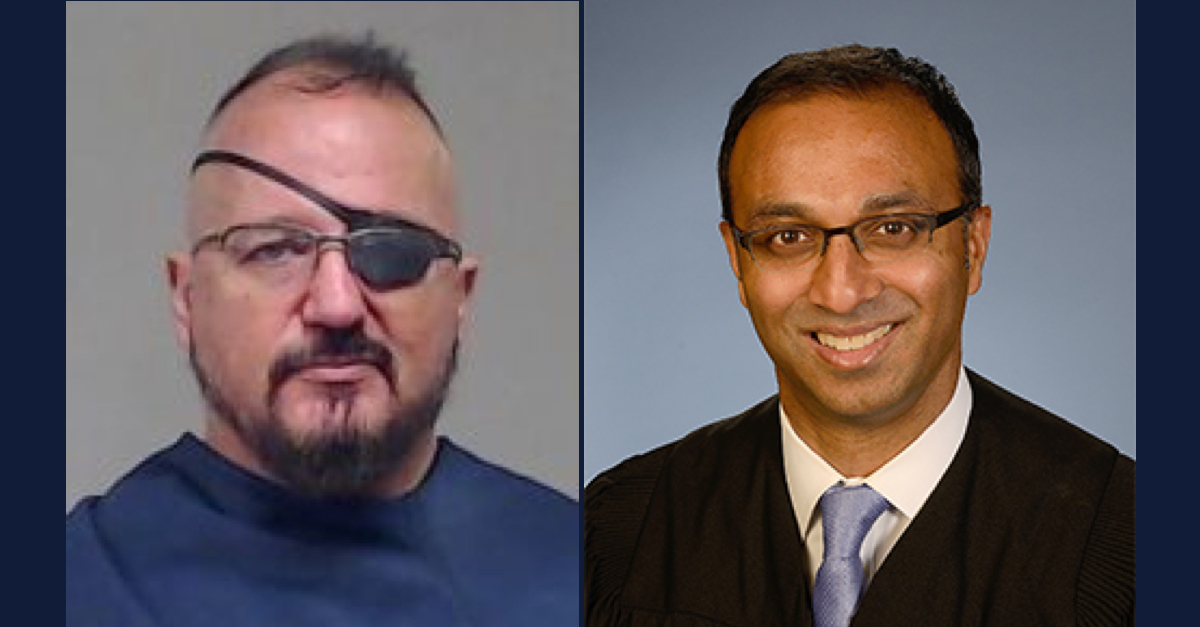

Left: Stewart Rhodes, via Collin County (Tex.) Jail. Right: U.S. District Judge Amit Mehta, via U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia.

The first jury note in the trial of top Oath Keepers leaders and members suggests that the panel has questions about the most serious count that the Justice Department leveled in the Jan. 6th investigation to date: seditious conspiracy.

Sometimes described as a lesser counterpart to treason, seditious conspiracy punishes any attempt to overthrow the government or stop the execution of its laws.

Rarely deployed since its passage in the Civil War era, the seditious conspiracy charges have become the centerpiece of two indictments against leaders of two extremist groups seen at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021: the Oath Keepers and the Proud Boys. The Oath Keepers facing that count are its founder Stewart Rhodes, Florida chapter leader Kelly Meggs, and members Jessica Watkins, Kenneth Harrelson, and Thomas Caldwell.

A handwritten note submitted shortly before noon on Monday, the second full day of deliberations in the case, showed jurors have been grappling with the charge.

It read:

Seditious conspiracy charge:Clarify: “prevent, hinder, or delay the execution of any law of the U.S.[“]vs“governing the transfer of presidential power, including the US Constitution.[“]

Rhodes, who founded the anti-government Oath Keepers militia group following the election of Barack Obama, and his co-defendants are charged with conspiring to use force to stop Joe Biden from taking office after his 2020 electoral win over Donald Trump. They are accused of amassing a cache of weapons as part of a Quick Reaction Force, or QRF, which Rhodes would allegedly have deployed if Trump had invoked the Insurrection Act and “called up” militias such as the Oath Keepers. The weapons were stored in a hotel room in Arlington, Virginia, and evidence suggests that defendant Caldwell had tried to procure a boat to ferry them across the Potomac to the Capitol.

The QRF never deployed, and closing arguments over the largely undisputed evidence circled primarily over whether to interpret these plans as a sincere effort to overthrow the government or inchoate bluster. Prosecutors told jurors that the Oath Keepers’ often-chilling and violent messages showed “real” and “sincere” plans — long before and after the certification of Biden’s victory — to prevent the transfer of power. Defense attorneys argued there was no plan, only a lot of bluster and “locker room talk.”

U.S. District Judge Amit Mehta told the lawyers in the case that it appeared to him that the jury was having trouble connecting some of the legal concepts underlying the seditious conspiracy charge. Assistant U.S. Attorney Jeffrey Nestler requested that the jury be advised that the U.S. Constitution is a law that governs the transfer of presidential power.

Mehta brought the jury back in to the courtroom and offered a clarifying instruction.

“The seditious conspiracy charge alleges as one of its two objects to prevent, hinder, or delay the execution of any law of the U.S. by force. The law of the U.S. for purposes of this charge are the laws governing the presidential transfer of power[.]”

Mehta cited the 12th Amendment of the Constitution, which says the winner of the Electoral College wins the presidential election, and the U.S. Code section mandating that Congress certify the Electoral College votes on Jan. 6.

Mehta then referred the jurors to the jury instructions, particularly page 24, which provides more detailed definitions of the statute’s text and emphasizes: “An agreement to merely violate the law is not sufficient.”

The judge then dismissed the jury and told the lawyers that he would see them soon, wryly adding a “maybe” to the end of his sentence.

Testimony in the Oath Keepers case began on Oct. 3 and continued for some seven weeks, finally going to the jury just two days before Thanksgiving. Monday marks the second full day of jury deliberations in the first of two Oath Keepers cases; the remaining co-defendants in this case — Roberto Minuta, Ed Vallejo, Joseph Hackett, and David Moerschel — are set to face trial in December.

Two co-defendants, Joshua James and Brian Ulrich, had previously pleaded guilty and have been cooperating with the government’s prosecution.

Seditious conspiracy is the most serious charge levied so far in the federal government’s expansive prosecution of rioters who, on Jan. 6, surged past police and breached the Capitol building as Congress was certifying Biden as the winner of the 2020 election.

The mob’s unlawful presence in the building brought Congress to a halt for several hours and forced lawmakers to either shelter in place or evacuate the building.

Each of the Oath Keepers defendants faces a raft of other charges in addition to seditious conspiracy, which carries a potential 20-year prison sentence, including obstruction of an official proceeding of Congress, destruction of government property destruction of evidence, and civil disorder.

Legal experts say that a question such as this one from the jury may mean at least one juror has some doubt — or maybe not.

“Generally, absent a verdict the best chance to gauge the jury is through a question,” former federal prosecutor Michael Harwin, who is not connected to the case, explained to Law&Crime. “All else being equal, the defense prefers the questions. The prosecution generally wants a simple straightforward conviction.”

A question from the jury can “generally be indicative of someone’s doubt,” Harwin said, although “not always, obviously.” Harwin said this particular type of question — seeking clarification about the underlying law — is “formulaic” and may not mean anything.

[Image of Stewart Rhodes, via Collin County (Tex.) Jail. Image of U.S. District Judge Amit Mehta, via U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia.]