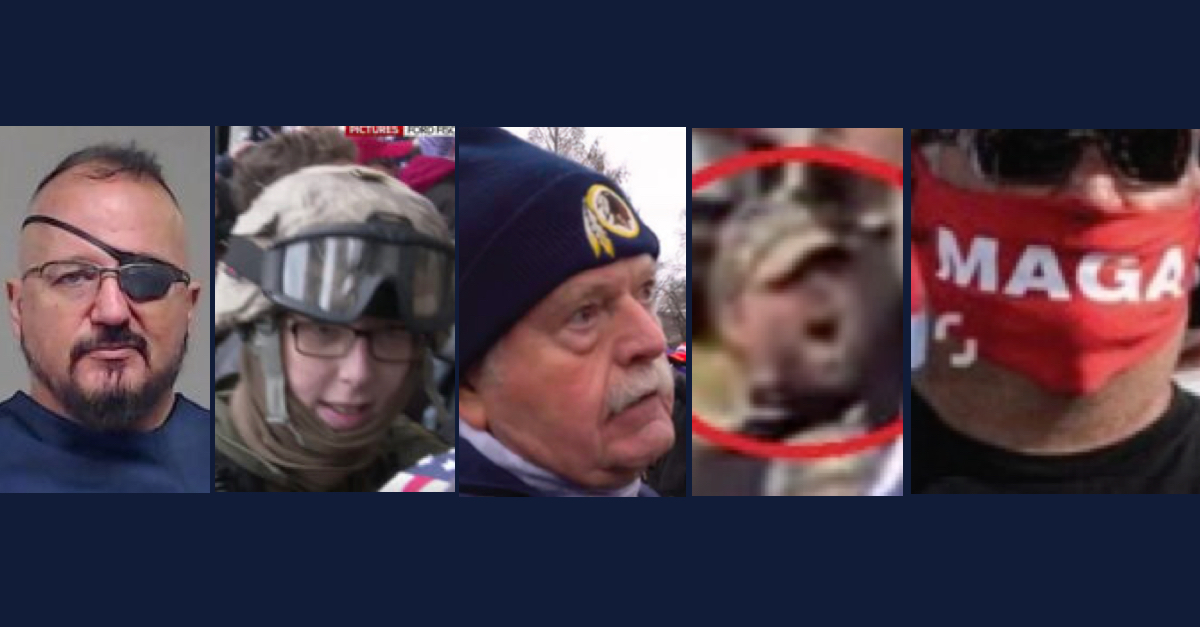

Left-Right: Stewart Rhodes, Jessica Watkins, Thomas Caldwell, Kenneth Harrelson, Kelly Meggs. (Image of Rhodes via the Collin County, Texas Jail; other images via FBI court filings.)

Opening statements in the trial of five members of the Oath Keepers group charged with seditious conspiracy in the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol began Monday morning, with federal prosecutors previewing evidence that they say will show months of planning on the part of the defendants, and efforts to delete incriminating evidence afterwards.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Jeffrey Nestler laid out what the jury can expect in the coming weeks as prosecutors will attempt to prove its seditious conspiracy case against Oath Keepers leader Stewart Rhodes and four of his co-defendants charged with seditious conspiracy and other crimes in connection with the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol.

Rhodes, Jessica Watkins, Kenneth Harrelson, Thomas Caldwell, and Kelly Meggs are charged with plotting to stop Congress from certifying Joe Biden‘s win in the 2020 presidential election and keeping Donald Trump in power. They are accused, along with four other co-defendants set to be tried in November, of conspiring to travel to Washington, D.C. ahead of Trump’s so-called “Stop the Steal” rally, and preparing a “Quick Reaction Force” standing at the ready to bring a cache of weapons allegedly stored in a Virginia to the Capitol. Members of the group could be seen allegedly approaching the Capitol using a “stack formation” to force its way through the crowd.

“The Defendants Seized Upon the Opportunity to Disrupt Congress.”

Nestler, standing at a podium directly in front of the 16 jurors, said that over the course of the coming weeks, prosecutors would show that the defendants were looking for the chance to block Biden from taking office, and that Jan. 6 — when the House of Representatives and Senate met in a joint session required by the Constitution — eventually provided that opportunity. They came to Washington, Nestler said, prepared for violence on Jan. 6, breached the Capitol using military-style maneuvers — celebrating their achievements afterwards — and then, in the days and weeks afterwards, deleted incriminating evidence.

“The defendants seized upon the opportunity to disrupt Congress,” Nestler said. “If Congress could not meet, Congress could not declare a winner.”

When the defendants “descended upon D.C.” the defendants attacked not just the government, not just Congress, but the country itself, Nestler added.

Describing Rhodes as someone with an “impressive pedigree” — citing the fact that he’s a graduate of Yale Law School, a former military paratrooper, and a one-time Congressional staffer — Nestler said that the Oath Keepers leader was “careful with both words and actions.”

Rhodes knew, for example, that if Oath Keepers members were caught with weapons inside the District of Columbia, they would lose what Nestler described as “access to manpower and firepower” — and that’s why Rhodes made the “calculated” decision to set up the so-called “Quick Reaction Force” at a hotel in Arlington, Virginia.

Even that decision, however, was strategic: according to Nestler, the QRF was under the command of Caldwell, a Navy veteran who was chosen to for that particular post that day because of his “water experience” and presumed expertise in using boats to transport weapons.

Nestler also said that Rhodes took efforts to mask his conspiratorial efforts, including speaking in “code” or “shorthand,” sending messages using phones other than his own, and, importantly, staying outside of the Capitol building, giving orders rather than actually participate in the breach.

The prosecutor appeared to prepare the jury for at least one probable defense tactic.

“You will hear evidence that they had more than one reason” for being in Washington, Nestler said, nodding to the expected argument from the defense that the Oath Keepers had no unlawful purpose that day. He acknowledged that it was certainly legal to be at Trump’s so-called “Stop the Steal” rally, and that even if the claims of providing security for VIPs were “a little suspect” because the group was neither licensed nor paid to do so, “even being bad security guards isn’t itself illegal.”

A legal purpose, however, doesn’t excuse “unlawful intent” on the part of the defendants, the prosecutor said.

Nestler also said that Rhodes used the Insurrection Act as “legal cover” for his plan, and that his reference to the Insurrection Act — which Rhodes publicly asked Trump to invoke several times — was simply “legal cover” for Rhodes’ conspiracy.

In his opening statements, Nestler included statements from defendants that appeared to show a tendency and inclination toward violence. He showed the jury pictures of patches, for example, that the prosecution alleges were affixed to a vest or backpack that Meggs was wearing that day.

“I don’t believe in anything,” the patch says. “I’m only here for the violence.”

Nestler also shared an audio recording taken on Jan. 10 of a meeting between Rhodes and at least one person in his inner circle. During that meeting, which was recorded by someone close to Rhodes who had become “alarmed” by Rhodes’ escalating rhetoric, Rhodes allegedly asked a confidante to pass along a message to Trump. While the participants of that meeting weren’t revealed, the audio recording was, and Rhodes could be heard sharing his regrets from Jan. 6.

“My only regret is we should have had rifles,” Rhodes could be heard saying on the recording, implying that if he and the Oath Keepers members had been armed, Congress would not have certified Biden’s electoral win.

The jurors remained mostly stoic during Nestler’s opening statements, although any facial reaction may have been obscured by the masks that everyone is required to wear while in the courtroom, except for when they are speaking on the records. Some, but not all, took notes on pads of paper provided by the court — notepads which, Mehta told the jury at the start of the day, would never be seen by him or anyone else, so “feel free to write whatever you want.”

Nor did the defendants’ faces or body language betray any emotion or reaction, although Caldwell could be seen taking notes throughout much of Nestler’s opening remarks, and Rhodes took notes occasionally.

Harrelson’s lawyer Geyer, however, made his displeasure clear when Nestler showed one video that purported to show defendants inside the Capitol building, repeatedly shouting the word “traitors.”

Geyer, who has previously filed motions suggesting that “suspicious actors” are responsible for the violence at the Capitol that day, was seen shaking his head repeatedly as the video played.

“What the Government Is Trying To Tell You Today Is Completely Wrong.”

Rhodes attorney Phillip Linder was the first of the defense lawyers to present opening statements. He framed the case as an amalgamation of weighty issues, including the First Amendment’s free speech guarantees, attorney-client privilege issues, the transition of presidential power, and whether Trump did actually invoke the Insurrection Act.

Perhaps in an attempt to highlight the stakes, Linder started to tell the jury that the defendants faced significant prison time, but was promptly interrupted by Nestler, who objected. Mehta agreed that bringing up possible sentence was out of line for an opening statement and sustained the objection.

Linder then started talking about the evidence in the case and how, he claimed, the government’s presentation of it lacks crucial context. The defense, Linder said, will show the “full picture of what happened that day.”

“I’m sure [prosecutors] will object to some of it, and that’s what we expect,” Linder said, before once again being thwarted by another objection from Nestler, which Mehta again sustained.

Linder then shifted focus to the defendants, making several references to how they have already been depicted by prosecutors and “the media.” The lawyer acknowledged that while even he “may not like some of what the defendants say, even though it may look inflammatory, they did nothing illegal.”

“What the government is trying to tell you today is completely wrong,” Linder added.

He then revealed that Rhodes does intend to testify on his behalf, noting that his client had previously “offered” to testify before the House committee investigating Jan. 6, but that Congress didn’t want it to happen.

Nestler, again, objected. Mehta sustained, and told Linder to avoid references in his opening statement to media coverage and the Jan. 6 committee.

Linder was thwarted again, moments later, when he told the jury that they would hear references to the Oath Keepers as “racist,” “sexist,” and “white supremacist,” among other negative characterizations. Nestler objected immediately. Linder’s reference to this possible testimony was somewhat surprising, as during jury selection, Caldwell attorney David Fischer had previously expressed concern about jurors who had heard the Oath Keepers described that way.

At the time, Mehta pledged that evidence of the Oath Keepers being a white supremacist organization would not be allowed at trial. On Monday, Mehta stuck to that pledge, sustaining Nestler’s objection and instructing the jury to disregard Linder’s reference.

“They’re not a violent group,” Linder said after the course correction, describing Rhodes as “extremely patriotic” and a “constitutional expert” who is facing criminal charges only because of his “good faith” reliance on the Insurrection Act.

“Stewart Rhodes meant no harm at the Capitol that day, Stewart Rhodes had no violent intentions that day,” Linder said, adding that the Oath Keepers are “basically a peacekeeping group” who “swore an oath” to “protect … and take care of” people.

Watkins’ attorney Fischer was somewhat more long-winded in his opening statements, going into great detail and speaking at length on behalf of his client Caldwell.

[Image of Stewart Rhodes via Collin County (Tex.) Jail; images of Jessica Watkins, Thomas Caldwell, Kenneth Harrelson, and Kelly Meggs via FBI court filings.]