On the eve of Thanksgiving, Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch concurred with a 5-4 decision to allow an injunction against the hypothetical future enforcement of New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo‘s COVID-19 executive orders to the extent that those orders ban certain large-scale religious gatherings. The justice’s choice of words to describe the plinth upon which a column of constitutional law rests, however, have raised several legal eyebrows. The column of law in question involves vaccination, medical treatments generally, birth control, forced sterilization, abortion rights, and even child labor laws.

Gorsuch’s analysis was somewhat lost under his pummeling of Cuomo for allowing New Yorkers to engage in commercial activities involving everything from “laundry and liquor” to “travel and tools” — but not religious activities involving large-scale worship services. Gorsuch slammed the governor for engaging in “exactly the kind of discrimination the First Amendment forbids.” Gorsuch also backhanded Chief Justice John Roberts for relying on a 1905 case seen by many—Gorsuch argues unrightfully so—as the pillar of public health law.

That case, about which Gorsuch spoke less than admirably, is Jacobson v. Massachusetts. In it, the Supreme Court allowed a city’s forced immunization schedule (backed by commonwealth laws) to stand against a Fourteenth Amendment complaint from a reverend who did not wish to be vaccinated against the pestilence of the day: smallpox.

The first Justice Harlan wrote:

[T]he legislature of Massachusetts required the inhabitants of a city or town to be vaccinated only when, in the opinion of the Board of Health, that was necessary for the public health or the public safety.[ . . . ]The state legislature proceeded upon the theory which recognized vaccination as at least an effective if not the best known way in which to meet and suppress the evils of a smallpox epidemic that imperilled [sic] an entire population.[ . . . ]Whatever may be thought of the expediency of this statute, it cannot be affirmed to be, beyond question, in palpable conflict with the Constitution.

Jacobson is sometimes interpreted as a carte blanche pass for the government to enact compulsory inoculation laws. However, as both Gorsuch and others have noted, the Jacobson opinion predates modern tiers of judicial scrutiny. Most of the time, courts view constitutional challenges to government actions under what’s called rational basis review. If the government wishes to regulate something, practically any rational basis for the regulation will suffice. Most regulations withstand criticism when viewed through this lax judicial lens. However, when it comes to fundamental rights (e.g., the First Amendment) or suspect classifications of people (e.g., racial classifications), the courts look probingly and harshly at the actions being challenged. Statutes or acts subjected to this “strict scrutiny” (not “normal” scrutiny) must serve a “compelling” governmental interest. If they do not, courts invalidate them as unconstitutional.

The strict scrutiny analysis goes like this: (1) does a fundamental right exist; (2) is the right is infringed; (3) does the government has a compelling justification for infringing on the right; and (4) if a fundamental right is infringed, is the infringement narrowly tailored to serve the compelling government objective?

Many legal scholars, such as the preeminent Erwin Chemerinsky, have suggested that the Jacobson holding fits the pattern of—or would at least survive—strict scrutiny. Borrowing language from the modern interpretive framework (but not from Jacobson itself), Chemerinsky has written that a “compelling interest in stopping the spread of communicable diseases” was implicit in the Jacobson holding. (Jacobson used the word “compelled” to describe the Massachusetts legislature’s acceptance of vaccines based “common belief maintained by high medical authority”; the decision noted in the language of its day that the legislature debunked or disregarded an alternate anti-vaccine message when choosing a smallpox policy.)

Even those who believe Jacobson was written under something akin to the more lax standard of rational basis review and who are critical of Jacobson‘s applicability towards vaccination in general have seemingly agreed that serious pandemics are different. One critical law review noted that “[t]he government interest protected in Jacobson would no doubt be considered compelling by today’s standards . . . a real threat to the safety of the entire community is a compelling state interest that satisfies the first prong of strict scrutiny analysis.”

Gorsuch has pitched his tent in the camp of those who believe Jacobson is a rational basis decision which has its own inherent problems. More on those in a moment.

First, however, let’s discuss Gorsuch’s core holding: New York’s COVID-19 executive orders must be jettisoned against the First Amendment because religious claims require a strict scrutiny analysis and, thus, restrictions must be narrowly tailored to serve a compelling interest. Gorsuch writes:

Although Jacobson predated the modern tiers of scrutiny, this Court essentially applied rational basis review to Henning Jacobson’s challenge to a state law that, in light of an ongoing smallpox pandemic, required individuals to take a vaccine, pay a $5 fine, or establish that they qualified for an exemption. [Citations omitted.] Rational basis review is the test this Court normally applies to Fourteenth Amendment challenges, so long as they do not involve suspect classifications based on race or some other ground, or a claim of fundamental right. . . . Here, that means strict scrutiny: The First Amendment traditionally requires a State to treat religious exercises at least as well as comparable secular activities unless it can meet the demands of strict scrutiny—showing it has employed the most narrowly tailored means available to satisfy a compelling state interest.

The narrow tailoring is Gorsuch’s primary issue: Gov. Cuomo let people shop for booze but not attend mass services, remember? Gorsuch dodged the issue of whether the governor had successfully articulated a compelling interest in preventing the spread of COVID through “red zones,” shutdowns, and the like. Instead, he re-litigated the vaccine laws at issue in Jacobson. He said those laws “easily survived rational basis review, and might even have survived strict scrutiny, given the opt-outs available to certain objectors.”

“Nothing in Jacobson purported to address, let alone approve, such serious and long-lasting intrusions into settled constitutional rights,” he said, ignoring that Jacobson was a reverend — yes, a religious leader — who claimed he suffered ill effects from previous vaccinations.

Had the Rev. Jacobson presented his case as one involving religious liberty under the First Amendment, rather than as a substantive due process case under the 14th Amendment, and had Gorsuch been on the bench in 1905, it seems likely Gorsuch would have been in the dissent. (Jacobson was a 7-2 decision.)

Critically, though, Gorsuch snapped into sharp focus what some justices blur: he drew a harsh line between rights explicitly granted by the Constitution (e.g., the First Amendment rights to speech and religion) and rights presumably read between the lines of the Constitution’s text. An example of the latter, “bodily integrity,” drew a significant degree of Gorsuch ire: he said the “right” is merely “hiding in the Constitution’s penumbras.” Here’s Gorsuch’s thoughts on what he perceives to be the fuzziness of that right:

Mr. Jacobson claimed that he possessed an implied “substantive due process” right to “bodily integrity” that emanated from the Fourteenth Amendment and allowed him to avoid not only the vaccine but also the $5 fine (about $140 today) and the need to show he qualified for an exemption. This Court disagreed. But what does that have to do with our circumstances? Even if judges may impose emergency restrictions on rights that some of them have found hiding in the Constitution’s penumbras, it does not follow that the same fate should befall the textually explicit right to religious exercise. Finally, consider the different nature of the restriction. In Jacobson, individuals could accept the vaccine, pay the fine, or identify a basis for exemption. The imposition on Mr. Jacobson’s claimed right to bodily integrity, thus, was avoidable and relatively modest.

The thrust of Gorsuch’s logic is that because the freedom of religion is explicitly enumerated in the text of the constitution, it must be held to be paramount, and that if the courts wish to protect other rights, they must also protect religious rights as well. But a few legal observers immediately jumped on the harsh treatment of Jacobson in attempts to read the tea leaves of what cases might fall next:

Some history is necessary here. In Jacobson, Justice Harlan opined that while the Fourteenth Amendment generally secures protections against government meddling with individual liberty, such liberty rights can from time to time be infringed by the government. A citizen may, Harlan wrote at the time, “be compelled, by force if need be, against . . . even his religious or political convictions, to take his place in the ranks of the army of his country and risk the chance of being shot down in its defense.” Harlan thus ruled that the public could not always “guard itself against . . . reasonable regulations established by the constituted authorities, under the sanction of the State, for the purpose of protecting the public collectively against such danger.” In other words, individual rights are not absolute, and the government can — under Jacobson and several other cases — invade upon them from time to time.

The Fourteenth Amendment was increasingly interpreted to imply more than freedom from “bodily restraint.” Though Jacobson held that the government need not respect the boundaries of what Gorsuch called “bodily integrity” in realms involving public health, opposite rulings occurred when the health care contemplated was merely private in nature. Griswold v. Connecticut held that the government could not make birth control illegal for husbands and wives; Roe v. Wade held that the government could not ban abortions in early stages of pregnancy; Planned Parenthood v. Casey affirmed most of Roe but upheld a few abortion-related restrictions. Griswold, Roe, and Casey all cite Jacobson. So do the analogous key decisions of Cruzan v. Director, Mo. Dept. of Health (holding family cannot order the state to ‘pull the plug’ on an “irreversibly comatose” patient) and Prince v. Massachusetts (holding state labor laws could prevent Jehovah’s Witnesses from engaging in child labor). Jacobson was also cited in another matter involving the citizenry as a whole, rather than just the individual: Gillette v. United States held that conscientious objectors could be forced into compulsory military service. “Our cases do not at their farthest reach support the proposition that a stance of conscientious opposition relieves an objector from any colliding duty fixed by a democratic government,” that case noted while examining a distinguishable matter of public importance — not of private concern. To sum up, Jacobson stands for the base premise that courts personal freedoms—so long as they don’t infringe on others’ freedoms.

Gorsuch’s concurrence may ultimately be a beacon for those attempting to chip away at such lines of jurisprudence, or perhaps it is best interpreted narrowly on its terms: strict scrutiny applies to infringements upon religious liberties, and such infringements must be narrowly tailored if they are to survive judicial scrutiny. There is nothing new about that. However, Gorsuch’s jabs at bodily integrity as a legal concept must be duly noted. So must his theories about mandatory vaccination laws requiring “opt-outs” for objectors. So must his vision for the role of the court: “In far too many places, for far too long, our first freedom has fallen on deaf ears,” Gorsuch wrote. To wit:

Why have some mistaken this Court’s modest decision in Jacobson for a towering authority that overshadows the Constitution during a pandemic? In the end, I can only surmise that much of the answer lies in a particular judicial impulse to stay out of the way in times of crisis. But if that impulse may be understandable or even admirable in other circumstances, we may not shelter in place when the Constitution is under attack. Things never go well when we do.

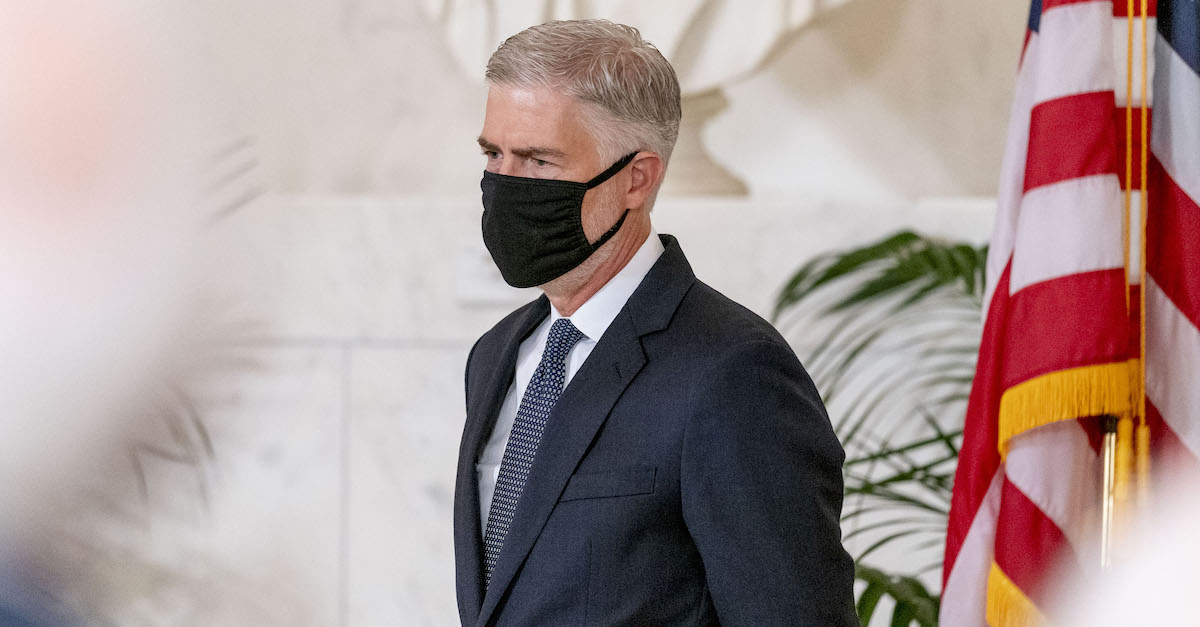

[Image via Andrew Harnik/Pool/Getty Images]