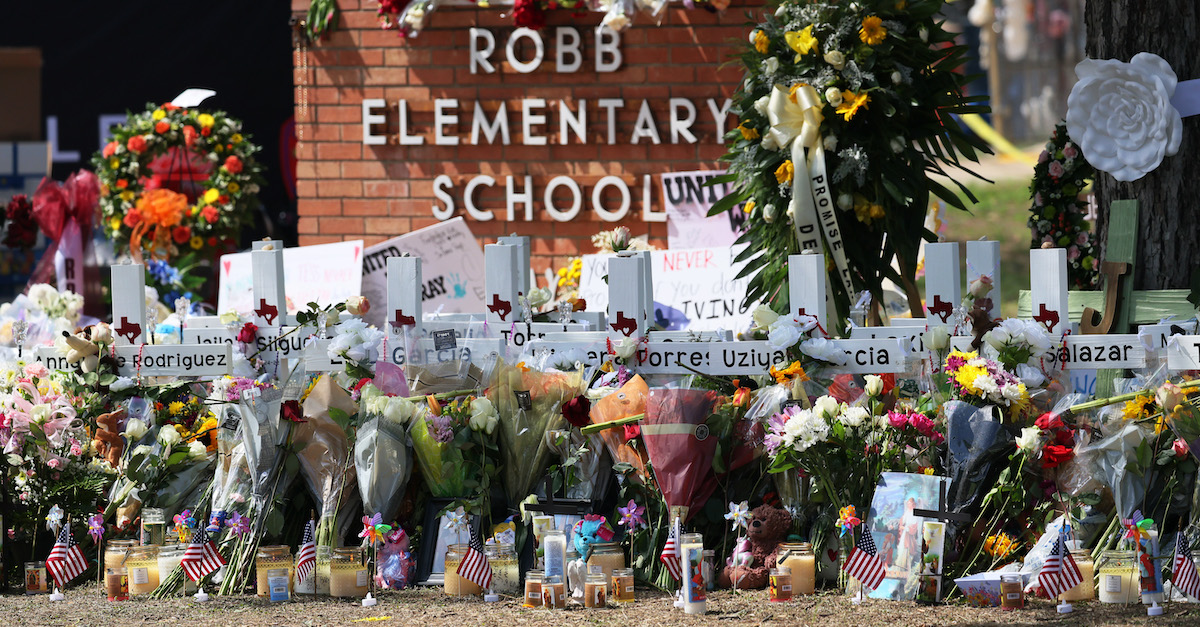

A memorial for the victims of Tuesday’s mass shooting at Robb Elementary School is seen on Friday, May 27, 2022 in Uvalde, Texas. Nineteen children and two adults were killed. (Photo by Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images.)

The law enforcement narrative about precisely what occurred this Tuesday when gunman Salvador Ramos killed 19 children and two teachers at a Uvalde, Texas elementary school has changed, changed, and changed again, but one thing has not: the law. And the law does not require police officers to rush guns-blazing into any dangerous situation, despite the fact that officers do sometimes put themselves in harm’s way to save innocent lives.

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott (R) on Wednesday touted the “amazing courage” of the police officers who he claimed were “running toward gunfire” to end the killing spree. By Friday, Abbott backtracked. He said he was “livid” to learn that officers waited about an hour to neutralize the gunman as children lay dying on the floor — some of them calling 911 and begging the police to save them.

Abbott claims he was originally “misled” on the facts.

Ramos shot his grandmother, fled, and crashed his truck at 11:28 a.m., the Associated Press wrote after compiling the law enforcement timeline. He entered Robb Elementary School at 11:33 a.m. and wasn’t dead until 12:58 p.m. by AP estimates.

“Please send the police now,” one girl pleaded by telephone while trapped in her classroom. The police waited more than 45 minutes to enter the room, authorities confirmed on Friday.

“It was the wrong decision,” said Steven McCraw, the head of the Texas Department of Public Safety.

NBC News reported that federal law enforcement agents were asked to stand down when they arrived at the scene. They finally went against the commands of local authorities, entered the school, and shot and killed Ramos, NBC said.

The shocking facts stand as a stark reminder of the underlying law. Despite frequent calls by the NRA — which included comments by Wayne LaPierre on Friday — and by conservative politicians for more police officers as a solution to mass shootings, the police have no legal duty to act to protect people when mass shootings occur.

Dan Cogdell, a Texas litigation attorney with Jones Walker LLP, told Law&Crime on Friday that Abbott’s most recent criticism of the police for not rushing into the school “is like the Menendez Brothers complaining about being orphans.”

“There is no legal obligation in Texas on the part of law enforcement to rush in as soon as they can,” Codgell said by telephone. “There’s just not — civil or criminal.”

Codgell said the public oftentimes confuses the actual legal obligations of law enforcement officers with what the police are taught and trained to do.

“Everybody’s going to hate law enforcement for not being the heroes we expect them to be, despite there not being a legal duty to act,” the attorney noted.

A May 24, 2022 ABC News screengrab shows the scene outside Robb Elementary in Uvalde, Texas.

“Anyone that knows anything about active shooters — rule one is to interact and take action as quickly as possible,” Codgell said while referencing officers’ suggested training standards. “No one can or should argue about that for the obvious reason that they [the shooters] are taking lives.”

He noted that “the first hour is absolutely critical” in attempting to rescue those who have been shot but not immediately killed. In Uvalde, Texas, students were dying as law enforcement remained idle.

Indeed, local training documents in Uvalde are being widely referenced, reported, and criticized in connection with this week’s shooting. The facially tough-sounding standards espoused within those documents suggest fast action but contain many highly discretionary terms. For instance, one document uncovered by the New York Times says “[a] first responder unwilling to place the lives of the innocent above their own life should consider another career field” (emphasis ours).

In legal terms, the word “should” is not the same as the words “must” or “shall.” Indeed, the training documents contain many other discretionary terms: officers “will usually be required” to do things, are “expected to” do things, and they are even lectured about “best hope” scenarios as to their behavior. The terms are guidelines, not mandates.

Even though officers are “trained to intervene as quickly as possible, and that means immediately, there is no legal requirement for them to do that — civil or criminal,” Codgell reiterated. “The law doesn’t change.”

The “no duty to act” doctrine dates back to at least 1855 at the U.S. Supreme Court, and the Court has repeatedly reaffirmed the concept in cases like Deshaney v. Winnebago County Department of Social Services (1989). The could held 6-3 in Deshaney that a so-called “child protection team” had no duty to protect a child despite repeated and severe beatings.

Then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist, a conservative jurist appointed by Richard Nixon and elevated by Ronald Reagan, wrote that “nothing in the language of the Due Process Clause itself requires the State to protect the life, liberty, and property of its citizens against invasion by private actors.”

“The Clause is phrased as a limitation on the state’s power to act, not as a guarantee of certain minimal levels of safety and security,” Rehnquist ruled. “It forbids the State itself to deprive individuals of life, liberty, or property without ‘due process of law,’ but its language cannot fairly be extended to impose an affirmative obligation on the State to ensure that those interests do not come to harm through other means.”

Subsequent opinions have reaffirmed the holding. One notable 7-2 case involved the emergence mandatory arrest laws. Even when a restraining order exists, and even when state governments pass statutes that say the police “shall arrest” a restrained individual who is subsequently accused of a violation, the victim of the violence doesn’t have a “property interest” under the Constitution and cannot force the police to act, wrote conservative jurist Antonin Scalia. The case, Castle Rock v. Gonzales (2005), involved the abduction of three children by an estranged husband. The police didn’t hunt the husband down despite pleas from his wife, and the husband murdered the children during the ensuing delay.

The police didn’t bring the fight to the husband. The husband brought the fight to the police. Officers finally killed him when he finally showed up at a police station and opened fire. The officers shot him back.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg dissented and believed “the elimination of police discretion was integral to Colorado and its fellow states’ solution to the problem of underenforcement in domestic violence cases.” However, the general paradigm remained: police were not required to act to protect private citizens — even when state statutes and restraining orders nominally ordered them to do so.

In 1981, a Washington, D.C. appeals court distilled the law this way while wholeheartedly citing a lower court (citations omitted):

The Court . . . does not agree that defendants owed a specific legal duty to plaintiffs with respect to the allegations made in the amended complaint for the reason that the District of Columbia appears to follow the well-established rule that official police personnel and the government employing them are not generally liable to victims of criminal acts for failure to provide adequate police protection. This uniformly accepted rule rests upon the fundamental principle that a government and its agents are under no general duty to provide public services, such as police protection, to any particular individual citizen.

After saying that police departments are there to “benefit the community at large by promoting public peace, safety and good order,” the D.C. appeals court noted that “courts have without exception concluded that when a municipality or other governmental entity undertakes to furnish police services, it assumes a duty only to the public at large and not to individual members of the community.”

Attorney Codgell noted that teachers also do not have a legal duty to fight to the death when confronted with a mass shooter.

The lack of a legal requirement for police officers to act oftentimes stands in stark contrast to the messaging everyday Americans hear through public debates about how to stop mass shootings, Codgell agreed.

The litigation involving the Feb. 14, 2018 massacre at Parkland, Florida, is illustrative. However, there is a difference between accountability — a rear-facing attempt to ration consequences for what occurred in the past — and forward-looking mandates which place duties or mandatory requirements on future actors to accomplish certain things or to undertake specific acts.

Legal Lessons from Parkland

In a 458-page report, the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Commission ascertained that shooter Nikolas Cruz entered the facility through a gate that was supposed to have been locked. School resource officer and sheriff’s deputy Scot Peterson was on the school’s campus but was not wearing a ballistic vest. He didn’t confront Cruz. He also didn’t, as a recent Men’s Health story noted, become a victim.

“I go to bed every night knowing I did the best I could with the information I had, which was nothing,” Peterson told writer Eric Barton in an extended profile.

Scot Peterson. (Mugshot via the Florida Department of Law Enforcement.)

Peterson is charged with 11 crimes in connection with his actions: seven counts of child neglect which resulted in bodily harm (all are second-second felonies), three counts of culpable negligence (which are second-degree misdemeanors), and one count of perjury in a non-official proceeding (a first-degree misdemeanor).

The Commission said after a thorough review of the case that Peterson “provided answers to various questions that were inconsistent with his training by BSO and inconsistent with common law enforcement practices” when he spoke to NBC’s “Today” show after the shooting. The report also said Peterson’s statements about his own actions to a Broward Sheriff’s Office homicide detective were “false.” The report described Peterson as “pacing back and forth and breathing heavily” on the day of the shooting while saying “I don’t know . . . I don’t know . . . [o]h my God, I can’t believe this.” When confronted about these and other issues, Peterson quit his job and retired.

Donald Trump called Peterson a “coward” — a term Peterson’s lawyers contested.

“Peterson knew through his training that the appropriate response was to seek out the active shooter and not ‘containment,'” the Commission concluded — even though Peterson was initially a “solo” officer on the scene. But the Commission’s report was an effort to make factual “findings” and to produce “recommendations” — not to assign legal blame. It is meaty as an assessment but is not weighty as a statement of law.

Peterson pleaded not guilty to the 11 Broward County criminal charges. His attorney has argued that qualified immunity insulates him from lawsuits and that Peterson had no affirmative duty to rush toward danger to engage in a fight-to-the-death blaze of gunfire with Cruz. The full argument is laid out in a motion to dismiss dated July 18, 2019.

“Throughout history, there has been a long line of cases where prosecutors have attempted to stretch statutes to cover conduct that they consider criminal,” the defense wrote while citing and quoting an Ellen S. Podgor law review article.

Peterson’s lawyers explained by pointing to Peterson’s lack of a legal duty to act:

The instant case is yet another unfortunate example. In the case at bar, the State has stretched the child neglect, culpable negligence, and perjury statutes beyond their breaking points. The State’s legal theory was that the Defendant — as a deputy sheriff — was a “caregiver” of the students at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School and that he had a legal duty to enter Building 12. The State’s legal theory does not withstand serious scrutiny. As demonstrated below, the State’s tortured reading of the operative statutes must be rejected in light of well-established canons of statutory construction and binding precedent.

Peterson’s lawyers argued that it was absurd to assume that he was a legal “caregiver” for more than 3,000 students at Parkland.

“While this was a horrific tragedy, and Defendant wishes he could have saved the students from harm, ultimately he was under no legal duty to guarantee their safety,” the lawyers underscored in the document’s very first footnote.

“There is no statutory authority that required Peterson to enter Building 12 and engage Cruz in a gunfight,” the defense continued further in the document. “Further, the Florida Supreme Court has held that there is neither a duty for the enforcement of police functions, nor a duty to prevent the misconduct of third parties.”

“[P]olice officers do not owe a legal duty under the 5th & 14th amendments of the U.S. Constitution to protect citizens,” the defense went on, citing myriad state and federal cases to support the argument.

Indeed, the Broward Sheriff’s Office’s Active Shooter Policy “stated that ‘the sole deputy or a team of deputies may enter the area and/or structure to preserve life,” the defense said — with emphasis on the word “may.”

“[P]ermissive words grant discretion,” the defense added while pointing readers to a popular Antonin Scalia legal interpretation book.

“Simply put, there is no statutory nor constitutional duty that required Peterson to enter the school and confront Cruz, nor is there a mandatory policy by BSO that required Peterson to enter and confront Cruz,” the defense continued. “All three points lead to the inescapable conclusion that Peterson’s actions did not broaden a ‘zone of risk’ that posed a threat of harm to others.”

Florida school shooting suspect Nikolas Cruz was photographed in court on April 27, 2018, in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. (Photo by Taimy Alvarez/Sun-Sentinel/Pool.)

The defense said it was asinine to assume that Peterson, who “was not even wearing a bulletproof vest . . . would have been using his service pistol against Cruz’s AR-15.”

“Cruz was wielding an assault rifle with rounds that are capable of piercing bulletproof vests,” the document adds.

In a separate document, Peterson’s attorneys also pointed to Republican Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’s decision to remove from office Peterson’s boss, former Broward County Sheriff Scott Israel, on the grounds that Israel failed to train officers to respond to a mass shooting. Peterson’s attorneys say the executive branch — DeSantis and his prosecutors — should not be allowed to simultaneously blame Peterson for failing to act while blaming Israel for failing to train Peterson on how to act. (The Florida Supreme Court separately upheld DeSantis’s removal of Israel.)

When viewed from afar, the big picture shows the push and pull between the hopes of some politicians and the actual legal duties of law enforcement officers.

Peterson’s prosecutors responded by arguing that the immunity provisions contained in a broad collection of cases involved civil actions, not criminal prosecutions. They also pointed to a dichotomy between civil law (which generally says police have no duty to rescue private individuals) and criminal law (which, here, the state is seeking to use to punish an alleged failure to protect private individuals: “failing to protect the child from the acts of a third party”).

Judge Martin S. Fein, who is overseeing the matter, refused to grant Peterson’s motion to dismiss. Judge Fein agreed that the case presented first-of-their-kind questions — specifically, whether Peterson could be defined as an “other person responsible for a child’s welfare” pursuant to the statute under which he was charged — but said the jury could ultimately reach the decision.

Peterson’s case has not yet gone to trial. Even if it does result in a conviction, it won’t necessarily create an affirmative duty for officers to engage in firefights with mass shooters. It may strike a fear of punishment in some officers’ minds in certain types of mass shootings, but the question of how much more effort they would have to expend in order to evade a similar punishment would remain up for debate. Plus, the civil standards would remain the same.

Parkland Civil Litigation

With the criminal case against Peterson ongoing, the U.S. Department of Justice in March settled a civil suit by the Parkland families for $127.5 million.

“The settlement does not amount to an admission of fault by the United States,” the DOJ said in a press release. Rather, in return for the payment, the families agreed to dismiss with prejudice their claims against the federal government.

The federal civil lawsuit was not filed against the school district or even the State of Florida. It was filed against the U.S. Government. According to the original complaint, the FBI received a tip on Jan. 5, 2018 — more than a month before the Feb. 14, 2018 shooting — that Cruz “was going to slip into a school and start shooting the place up.”

“The FBI had non-discretionary obligations, governed by established protocols, to handle and investigate tips concerning potential school shootings in a reasonable manner — at minimum not ignore the information entirely — and to act against Cruz to prevent him from committing the mass shooting,” the plaintiffs argued. “Yet, contrary to its own established rules, the FBI failed to take any action whatsoever with the information it received. If the FBI had complied with its mandatory obligations to investigate and intervene in Cruz’s plans to carry out a mass shooting at Stoneman Douglas High School, Cruz would not have succeeded.”

The document alleged that the ensuing carnage was a “direct, proximate, and foreseeable result of the FBI’s negligence.”

Students exited the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School single-file on Feb. 14, 2020. (Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images.)

Legally speaking, the federal government is generally not responsible for its own torts under a doctrine called sovereign immunity. However, the Federal Tort Claims Act waives that doctrine in limited areas. The legal key that unlocked the Parkland case turned out to be a much earlier matter involving a lighthouse. Because the government had been previously held liable for a tugboat that wrecked due to an extinguished beacon in a government lighthouse, the plaintiffs argued that the government could be similarly held liable for failing to stop the Parkland shooting given the tip the FBI received about Cruz. The plaintiffs said the FBI voluntarily established a tip line that purported to be the correct receptacle for school threats:

In this case, the FBI’s tip intake specialist assured the tipster that the FBI, and not some other governmental body, was the proper forum for reporting school shooting threats. On the call, the tipster expressed some ambivalence about whether she was calling the correct governmental agency, saying, for example, that she “didn’t know whether to call you or Homeland Security or who,” and the FBI intake specialist responded by assuring the caller that the FBI appreciated that the tipster had chosen to call. The FBI intake specialist did not direct the caller to report her observations and concerns to anyone else. Either implicitly or explicitly, the FBI assured the tipster that she had reported her information to the right place.

Because the government assumed a duty to act on the tip and failed in its duty, it could be held liable, the plaintiffs asserted. (They also pointed to the use of streetlights as an example.)

The facts which gave rise to the settlement were highly specific as to the FBI’s receipt of a tip about Nikolas Cruz. Without a concrete and particularized tip, the federal government’s hearty assertions that it owed no duty of care to protect the plaintiffs would likely have carried the day.

Because the case settled before it was tried in court, it did not result in a change in law: no court held that the FBI affirmatively has a duty, as the plaintiffs argued, to act on tips it receives in order to save lives. The government’s embarrassment, however, likely influenced the payout as a matter of public relations, attorney Cogdell said to Law&Crime on Friday.

But assume the FBI had acted. The action would not have involved a confrontation with a mass shooter, because a mass shooting was not occurring when the tip rolled in. The duty contemplated by the case would likely have been for the FBI to investigate and to secure a search warrant or perhaps even a mental health commitment. Or, maybe it would have been sufficient for the FBI to pass the tip along to local authorities or to a law enforcement task force.

State Civil Liability

A Florida state law limits state liability for any single “incident or occurrence” to a total sum of $300,000. With reference to the Parkland shooting, the Florida Supreme Court in September 2020 upheld that limit — meaning the individual victims would only receive a fraction of the total liability for the incident. That meant, according to ABC News, about $9,000 per victim. Any deviation from that award would require approval by the state legislature and by the governor, ABC noted.

In a response to a lawsuit against it by Parkland families, the School Board of Broward County said that Cruz was the “sole proximate cause” of the shooting spree and, because he had not been a student for “approximately one year,” the school had not way to “predict his future conduct.” Therefore, the wrongdoing was caused by an independent third party, not by the district, and the district said it could not be held liable for damages. The district did admit that it had a duty to provide security but did not expound on that duty in its initial response to the lawsuit.

The school board eventually agreed to a $25 million settlement in October 2021, according to WPLG-TV in Miami.

While the settlements certainly penalize the government’s coffers for alleged failures to act, none resulted in a ruling by a court of law that the police had an affirmative duty to dodge bullets in an attempt to save lives.

So, What’s the Remedy?

The longstanding axiom that the police do not have a legal duty to rush into danger and to engage in a fire-fight to the death with a mass murderer is longstanding and well settled — as a civil matter. The criminal case against Scot Peterson is novel, and it may change those longstanding civil notions — or, it may not, depending on how it proceeds. Even if Peterson is convicted, it won’t be because he failed to fight to the death. It will be because he failed to act as a caretaker as a sole individual for thousands of students. The precise nature of what acts would have been appropriate for a “caretaker” would remain up to debate. Similarly situated enforcement officers would arguably have to do more than he did — perhaps just a little more — in order to evade criminal liability. And, the precise nature of criminal liability can vary widely state to state. A law employed against Peterson might not necessarily have an analogue in another state.

As the Parkland cases illustrate, civil litigation may result in millions of dollars — or just a few thousand dollars — in civil damages. In an era of much-touted and much-parroted tort reform, the government may be disinclined to order its police forces to engage in danger if it can simultaneously limit its liability for their failures to stop mayhem immediately. But, the highest profile shootings may lead to calls from constituents to act — and politicians may be inclined to offer payouts proportional to the amount of attention a case receives.

That brings us back to Texas.

“Do I think there will be a civil recovery against officers or civil agencies?” attorney Dan Cogdell asked aloud while on the phone with Law&Crime Friday afternoon. “Probably not.”

“Civil recovery against the officers and the school district will be extremely difficult,” he suggested.

People make a human chain as they pay tribute to school shooting victims in front of the Uvalde County Courthouse in Uvalde, Texas, on May 26, 2022. (Photo by Chandan Khanna/AFP via Getty Images.)

Cogdell said civil recovery under Texas law and within the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit is more complicated than it is in other jurisdictions. A successful plaintiff would have to prove a core tort — negligence or perhaps a civil rights claim — and prove that the government had a “habit, custom, and practice” within a named agency of engaging in the alleged tortious action. That additional bar to recovery would likely plague Uvalde plaintiffs, Cogdell predicted.

“Absent a written policy statement from the agencies, you’re not going to get there,” Cogdell said of a possible monetary recovery. And, “even if a jury orders an award, an appellate court would likely wipe away the settlement.”

That assumes the government would be audacious enough to take the case all the way to trial. Cogdell said a good plaintiff’s lawyer might sue Uvalde for not providing adequate security — and school officials might agree to get its insurance carrier to pay the policy limits “because they feel morally responsible.”

If Cogdell were representing Uvalde plaintiffs, he said his first litigation target would hypothetically be “a solvent defendant that doesn’t have any immunity,” such as “an outside security agency that a school district has hired” — assuming one exists.

Then, he would probably target the school district.

“While they have a sovereign immunity argument, it’s going to be really sexy for a plaintiff’s lawyer to sue the school district because they’re going to be an unpopular defendant in that community,” Cogdell said. “You might force them to a settlement you could never get sustained on appeal if there’s a verdict.”

That assumes the district is willing to roll over as a public relations matter, he noted.

The third target may be the local or state police, depending on who was on the scene and when, Cogdell said.

“None of them are a particularly viable candidate from a technical [legal] standpoint,” he agreed. “They’re going to assert their immunity.”

As a matter of law, the uneasy remedy seems to be this: if the facts allow, plaintiffs can sometimes secure financially lucrative but legally narrow payouts from the government due to the failures of agents at various levels, but the settlements thus far have not resulted in a documented legal duty for law enforcement officers to act to protect the public at large in the future. Though there is some old, minority case law which suggests a possible heightened duty in very specific circumstances, the law generally protects law enforcement hesitation. Adverse employment actions, such as the resignation of Scot Peterson and the removal of Sheriff Israel, are imprecise pressure tactics. Even with those options, and despite calls by politicians that officers act more like heroes and less like “cowards,” the general lack of a legal duty to rush into harm’s way remains intact — even if the public narrative surrounding mass shootings appears to suggest otherwise.

[Image via Jordan Vonderhaar/Getty Images]