Rep. Jim Hines (D-Connecticut) said that Bannon claimed a “remarkably broad definition of executive privilege,” but George Washington University Law Professor Jonathan Turley wrote in a recent blog post that this claim was meritless. Turley wrote that Bannon had “no basis for such a broad assertion of executive privilege,” and that he could get himself into trouble if doesn’t talk.

“Unless Bannon changes course,” Turley wrote, “he could be looking at contempt sanctions down the road.”

For starters, Turley said, the White House has to invoke executive privilege in advance, and they did not do so. Similar controversy ensued when Attorney General Jeff Sessions wouldn’t answer questions regarding his conversations with President Trump.

What makes Bannon’s situation arguably more problematic than Sessions’, is that that Bannon wasn’t just asked about his time in the White House, but also as a member of Trump’s transition team after the election and before he took office. Executive privilege is meant to protect the communications of the president, and Trump was not yet president at that time.

“The use of executive privilege over conversations with a president-elect is very hard to maintain,” Turley wrote.

2 U.S.C. § 192 says:

Every person who having been summoned as a witness by the authority of either House of Congress to give testimony … who, having appeared, refuses to answer any question pertinent to the question under inquiry, shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, punishable by a fine of not more than $1,000 nor less than $100 and imprisonment in a common jail for not less than one month nor more than twelve months.

Of course, even if Congress wants to hold Bannon in contempt, it would take a lengthy process before anything were to happen.

If a witness fails to comply with a congressional subpoena, committee rules generally require a majority vote of the full committee authorizing a resolution of noncompliance to be reported to the entire House of Representatives. After the matter is reported to the full House, a floor vote is taken to determine whether a resolution of contempt may be issued against the offending individual. It takes a majority vote in the House to approve a resolution of contempt.

Once the resolution of contempt passes the full House, Congress technically has two options to pick from in deciding how to proceed with the case.

First, the House may instruct its sergeant-at-arms to arrest the individual and bring them before the House presiding officer (usually the Speaker of the House, Paul Ryan). The individual could be held in the Capitol jail, but this practice has not been used for more than 80 years.

The second, and more practical option, is for the Speaker to refer the matter to U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia for criminal contempt proceedings. The law then requires the U.S. Attorney to enpanel a grand jury to consider indictments for criminal contempt.

It remains to be seen how Bannon will respond to subpoenas now. The White House has been accused of instructing Bannon not to talk, but given the recent rocky relationship between Bannon and Trump, the former adviser might not be willing maintain his silence if it means going to jail.

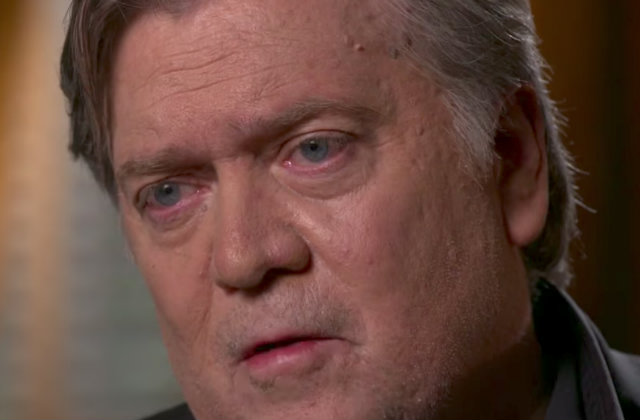

[Image via CBSN screengrab]