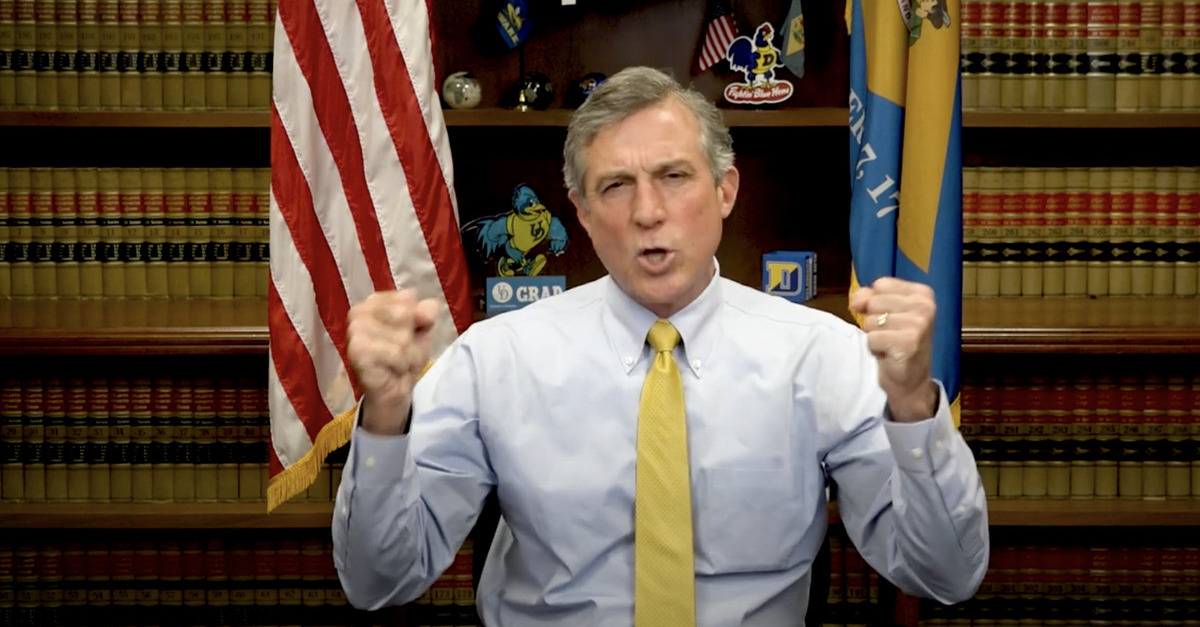

Gov. John Carney (D)

A lawsuit challenging Delaware’s “major party” rule for sitting judges will now forward after a federal judge refused to dismiss the case for lack of standing.

An earlier case related to the same issue filed by the same Delaware lawyer, political independent James Adams, was rejected by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2020. At the time, SCOTUS unanimously ruled that Adams lacked standing to challenge a provision in the state’s constitution that required Delaware’s major courts to maintain a “political balance” amongst sitting judges.

The defendant in Adams’ case is Governor John Carney (D) in his official capacity.

Article IV § 3 of the Delaware Constitution contains two provisions that regulate the composition courts within the state. The “bare majority requirement” requires that no more than a bare majority of judges on the Delaware Supreme Court, Court of Chancery, and Superior Court be affiliated with a single political party.

The corresponding “major political party” provision requires the remaining judges on those courts to to “be of the other major political party.” As a result, any person not affiliated with either the Republican or Democratic party is ineligible to serve as a judge on one of the state’s top courts.

Adams, a Democrat-turned-independent, filed a lawsuit challenging the provision, claiming it violated his First Amendment right to free speech and right to be considered for public office. Adams prevailed in his lawsuit, but when the case was appealed to the nation’s highest court, the ruling in Adams’ favor was overturned on procedural grounds. SCOTUS avoided the constitutional question and unanimously decided that Adams lacked Article III standing to sue, because he did not sufficiently demonstrate that he was “able and ready” to apply for a judgeship.

Adams filed a second lawsuit on the same day of the SCOTUS ruling, in which he altered his claim. In Adams’ complaint, he raised a Fourteenth Amendment equal protection challenge to Delaware’s rule. Adams argued that the provision treats politically unaffiliated lawyers differently from those who are members of major parties, and that although only the lowest level of scrutiny would be applicable, the rule fails rational basis scrutiny.

Adams worked as a lawyer in private practice for three years before joining the Delaware Department of Justice where he served as Assistant State Solicitor under the late son of President Joe Biden, Delaware Attorney General Beau Biden, according to his lawsuit. Adams also has also served as Deputy Division Director of the Family Division, which handles cases involving domestic violence, child abuse and neglect, child support orders, and juvenile delinquency and truancy.

In his complaint, Adams alleged that he applied for a positions as a judge in various Delaware state courts in 2017, 2018, 2020, and 2021. Adams said his 2017, 2018, and 2020 applications were rejected but that he had not received a response to his 2021 application at the time of filing. Adams argued that he maintains a genuine interest in becoming a judge.

Carney filed a motion to dismiss Adams’ complaint, arguing that Adams should be collaterally estopped from bringing this second lawsuit and that Adams continues to lack standing in any event.

U.S. District Judge Maryellen Noreika (a Donald Trump appointee) denied the governor’s motion to dismiss Friday, clearing the way for Adams’ lawsuit to move toward trial. In a 22-page ruling, Noreika found that the new facts Adams raised, as well as the lack of any improper conduct on Adams’ part, weighed against blocking his lawsuit through the use of collateral estoppel.

On the issue of standing, Noreika found that any problems that may have existed in the earlier case before SCOTUS have been cured in Adams’ refiling.

“The Supreme Court’s conclusion reflected the record before it,” said Noreika. SCOTUS’ findings, however, “did not, as Defendant seems to suggest, indelibly taint Plaintiff as a man who can never have a genuine interest in obtaining a judgeship,” the judge said.

Rather, Noreika explained, the court record in the earlier case indicated that Adams’ grievance had been “abstract” and “generalized.”

“But the record before this Court is different,” Noreika allowed, “and it demonstrates that Adams’s interest in a judgeship has matured into something concrete and genuine.” Furthermore, Adams may well apply for judgeships in the future, reasoned Noreika, who found Adams to be “able and ready” to do so.

Because Adams’ interest in being a judge is now “tangible and sincere,” and because his exclusion due to his lack of political affiliation would be an absolute bar from his consideration for a vacancy, Noreika ruled that Adams does indeed have standing to sue.

Adams’ claim — that Delaware’s “major party provision” violates his Fourteenth Amendment right to equal protection under the law — would require the finder of fact to determine whether there exists a legitimate state objective for the rule, and whether the rule is rationally related to achieving said objective. Although most laws survive this lowest level of constitutional scrutiny, a court may well find that discriminating against politically unaffiliated judicial candidates serves no cognizable government interest.

Attorneys for the parties did not immediately respond to request for comment.

[Image via Youtube/screengrab]