The pharmaceutical giant behind a top-selling baby powder will not be allowed to use a legal bankruptcy maneuver known as the “Texas Two-Step” to avoid having to pay billions to cancer victims.

A federal appeals court ruled Monday against a bankruptcy filing by a Johnson & Johnson subsidiary that judges said was little more than an attempted end run around having to pay judgment awards in the massive talcum powder litigation against the company.

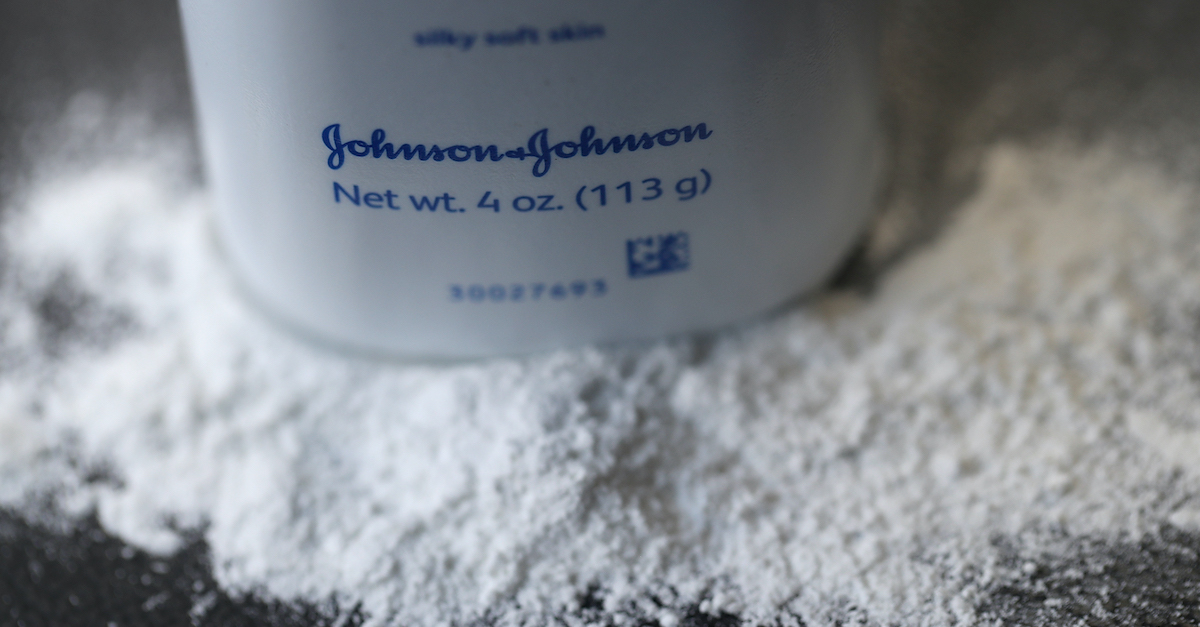

Johnson & Johnson (“J&J”), the maker of well-known products such as Band-Aid, Tylenol, Aveeno, Listerine — and of course, Johnson’s Baby Powder — was found liable in 2013 and 2016 when juries found that its talc-based products caused ovarian cancer and mesothelioma. Following those initial door-opening verdicts, nearly 40,000 more cases were filed; as the multi-billion-dollar verdicts poured in, many more were expected.

Thanks to an unusual feature in Texas state law, J&J was able to perform a “divisional merger.” The merger allowed J&J to create an entirely new subsidiary and transfer its liabilities into that subsidiary, while holding its assets in the original company. As a result, the debt-ridden newly-formed subsidiary could file for bankruptcy under Chapter 11 and thereby reduce or eliminate its obligation to pay out claims.

After the enormous talcum powder judgments were pronounced, J&J used the maneuver to spin off a new entity: LTL Management LLC (“LTL”), which held the talc litigation liabilities, while J&J retained virtually all of the company’s productive business assets.

The talc claimants sued to block the company’s attempt to freeze them out of collecting on their judgments by moving to dismiss LTL’s bankruptcy petition. The bankruptcy court sided against the plaintiffs and allowed the bankruptcy proceedings to continue.

A three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit reversed that decision Monday, blocking J&J’s attempt to use bankruptcy to sidestep tort judgments on the grounds that company’s “shell game” had not occurred in good faith.

The ruling was not only a huge win for thousands of talc claimants, but was precisely the result J&J tried to avoid with strategically-located litigation that criss-crossed the country. J&J, one of New Jersey’s largest and most profitable companies, created a subsidiary under Texas law, then filed bankruptcy in North Carolina. The Philadelphia-based Third Circuit was blunt in calling out J&J for its attempt to circumvent the very result it handed down in its ruling.

“We start, and stay, with good faith,” U.S. Circuit Judge Thomas Ambro wrote for the unanimous three-judge Third Circuit panel. Ambro, a Bill Clinton appointee, was joined by fellow judges Julio Fuentes, also appointed by Clinton, and Luis Felipe Restrepo, a Barack Obama appointee.

Ambro said in the ruling that bankruptcy filings require a good faith claim that the filer is in “financial distress.” The panel acknowledged that mass tort liability could certainly “push a debtor to the brink,” but that what matters is the debtor’s capacity to satisfy its obligations.

Ambro found that LTL was not in such financial distress that it lacked capacity to pay out verdicts to talc claimants. Rather, its relationship to J&J meant that both company’s assets should be taken into account when assessing LTL’s ability to pay. Because LTL had access to J&J’s “exceptionally strong balance sheet,” which included $400 billion in equity value “with a AAA credit rating” and “$31 billion just in cash and marketable securities,” its financial position did not warrant protection in bankruptcy.

Ambro had harsh words for J&J’s attempt to use Texas law to evade payouts, and called LTL “essentially a shell company” that suffered no meaningful financial difficulties “during its short life outside of bankruptcy.”

In ruling against LTL’s bankruptcy, the panel was clear to point out that the court isn’t anti-bankruptcy in all cases:

That said, we mean not to discourage lawyers from being inventive and management from experimenting with novel solutions. Creative crafting in the law can at times accrue to the benefit of all, or nearly all, stakeholders. Thus we need not lay down a rule that no nontraditional debtor could ever satisfy the Code’s good-faith requirement.

However, as it relates to LTL and J&J, the company’s attempt to essentially manufacture “financial distress” fails, the judges found.

In a footnote, Ambro also called attention to J&J’s failed attempt to find a friendly bench by forum-shopping. Ambro noted that it was “perhaps not by coincidence” that J&J “seem[ed] to prefer filing in the Fourth Circuit” — specifically, the North Carolina court where the bankruptcy began.

North Carolina lies within jurisdiction of the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, known for its low standards of “good faith” for bankruptcy cases.

However, U.S. Bankruptcy Judge J. Craig Whitley unceremoniously transferred the case to New Jersey on the grounds that neither the company nor the case had any connection with North Carolina. The Third Circuit’s ruling based on lack of good faith was likely just what J&J hoped to avoid.

J&J has two legal moves still in play: it could file for an en banc review by the full Third Circuit or it could file a petition for certiorari before the U.S. Supreme Court. Neither route offers a high probability of success for J&J: the decision was “precedential,” which means that Ambro’s draft decision was already circulated among the full Third Circuit (and presumably found acceptable by a majority thereof), and the Supreme Court has already denied cert in a related talc case against J&J.

Law&Crime reached out to Neal Katyal, who argued in favor of the bankruptcy to the Third Circuit, but did not receive a response.

[Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images]