A federal court of appeals handed the Biden administration a limited but significant victory on Wednesday by halting a lower court’s prior order that barred Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) from using a set of priorities to curtail certain immigration-related arrests.

Late last month in one of many cases stylized as Texas v. United States, U.S. District Judge Drew B. Tipton (who was appointed by Donald Trump) shocked immigration attorneys and legal experts when issuing a sprawling, 160-page opinion and order. In that ruling, the judge on the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas summarily wiped away all of ICE’s enforcement priorities based on a decidedly novel reading of two statutes contained in the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA).

According to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, Tipton’s reading of the law was incorrect. A panel opinion from Circuit Judges Gregg Costa (a Barack Obama appointee), Leslie H. Southwick (a George W. Bush appointee) and James E. Graves Jr. (also an Obama appointee) poked holes in the lower court’s legal analysis.

“The central merits issue is whether Congress has interfered with immigration officials’ traditional discretion to decide when to remove someone,” Costa wrote. “If not, then the interim priorities are the type of enforcement decisions that are ‘committed to agency discretion by law’ and not reviewable (for substance or procedure).”

The district court answered that question in the affirmative — holding that the two provisions of the IIRIRA at issue effectively mandate the arrest of a wide variety of undocumented immigrants and explicitly scrapping two separate Biden administration memos outlining new ICE enforcement priorities intended to tamp down on arrests. The appellate court’s 15-page opinion serves as a terse rejoinder to the district court’s lengthy ruling.

“[W]e do not see a strong justification for concluding that the IIRIRA detention statutes override the deep-rooted tradition of enforcement discretion when it comes to decisions that occur before detention, such as who should be subject to arrest, detainers, and removal proceedings,” Costa wrote. “That means the United States has shown a likelihood of prevailing on appeal to the extent the preliminary injunction prevents officials from relying on the memos’ enforcement priorities for nondetention decisions.”

Notably, however, the Fifth Circuit left in place a much more limited section of the injunction that “prevents the Attorney General from relying on the memos to release those who are facing enforcement actions and fall within the mandatory detention provisions” of the law.

“The likelihood of success factor requires a prediction,” Costa wrote–explaining the panel’s decision in favor of the Biden administration. “The first building block of our prediction is the strong background principle that the “who to charge” decision is committed to law enforcement discretion, including in the immigration arena. It is quite telling that neither the States [of Texas or Louisiana] nor the district court have cited a single Supreme Court case requiring law enforcement (state nor federal, criminal nor immigration) to bring charges against an individual or group of individuals.”

The appeals court goes on to fine-tune their efforts at showing how off-base they found the lower court’s understanding of the law to be:

What is more, in the quarter century that IIRIRA has been on the books, no court at any level previously has held that sections 1226(c)(1) or 1231(a)(2) eliminate immigration officials’ discretion to decide who to arrest or remove. The Supreme Court has recognized that detention under section 1226(c)(1) is mandatory “pending the outcome of removal proceedings.” But its cases considering the statute are ones in which detainees subject to enforcement action were seeking their release. The same is true of the recent case involving section 1231 in which already-removed detainees sought release. Those cases do not consider whether the statutes eliminate the government’s traditional prerogative to decide who to charge in enforcement proceedings (and thus who ends up being detained).

“And while the district court’s interpretation of these statutes is novel, executive branch memos listing immigration enforcement priorities are not,” Costa added acridly.

Similar recent cases have, the appellate court noted, interpreted parts of the relevant statutes, but those cases haven’t turned on the question of whether or not Congress, via IIRIRA, actually meant to wholly eradicate law enforcement’s traditional discretion to enforce the law. In other words, according to the three-judge panel, Tipton misapplied both the text of the statute and the case law that has subsequently clarified the statute’s actual meaning.

Costa’s ruling was also critical of the lawyering on display from the Lone Star State — the primary plaintiff in the case.

Counsel for Texas appeared to have given up part of the game, in the appellate court’s opinion, during oral argument by claiming that the Southern District of Texas injunction only mandates who must be detained and not who must be deported by the government. A footnote replies to that understanding of the district court’s order: “But if that is the case then the injunction is overbroad because it is a blanket prohibition on officials’ reliance on the interim priorities.”

Texas also claimed during oral argument that the IIRIRA requires detention for immigrants who will never be subject to deportation. The appeals court said that understanding was “at odds with the text” and a 2018 Supreme Court ruling interpreting the statute.

“There would, of course, be other concerns with indefinite detention for someone not facing removal,” Costa said.

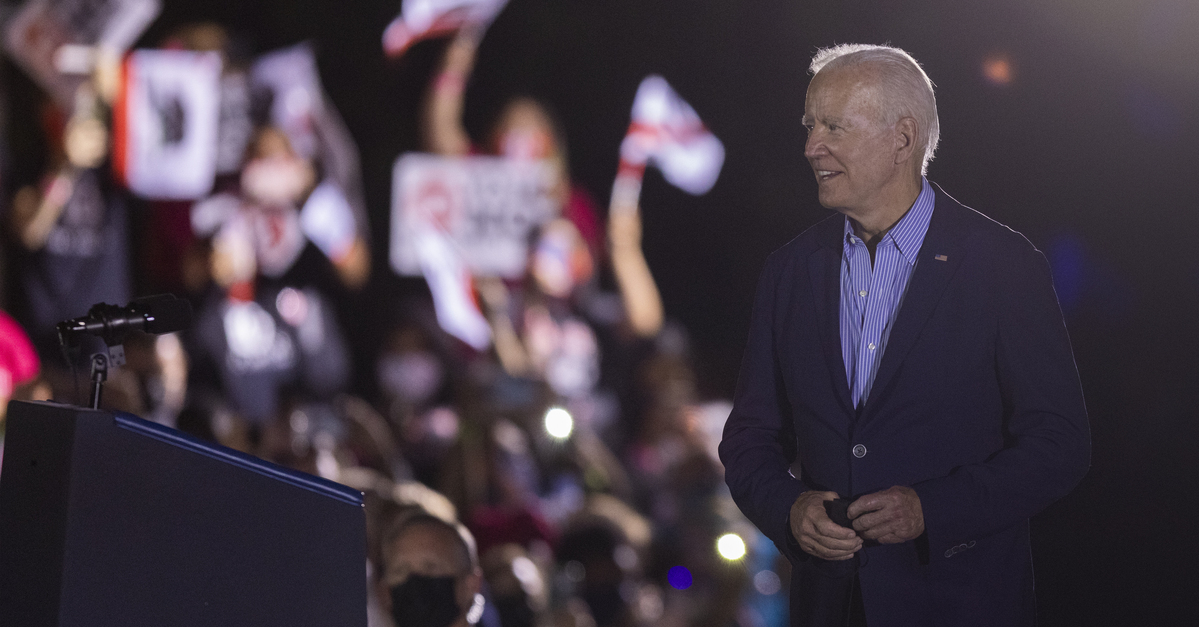

[image via David McNew/Getty Images]