The Trump administration was handed a thorough shellacking in the Southern District of New York (SDNY) on Tuesday morning when U.S. District Judge Jesse M. Furman issued a hefty 277-page opinion blocking the inclusion of a citizenship question on the 2020 census. For an in-depth run down on the ins-and-outs that decision see Law&Crime’s previous reporting here.

The numerous plaintiffs in the case had long argued that an “unconstitutional and arbitrary decision [was made] to add a citizenship demand to the 2020 Census questionnaire,” a question that would “fatally undermine the accuracy of the population count and cause tremendous harms to Plaintiffs and their residents.”

The question asked people to identify whether they are American citizens or not.

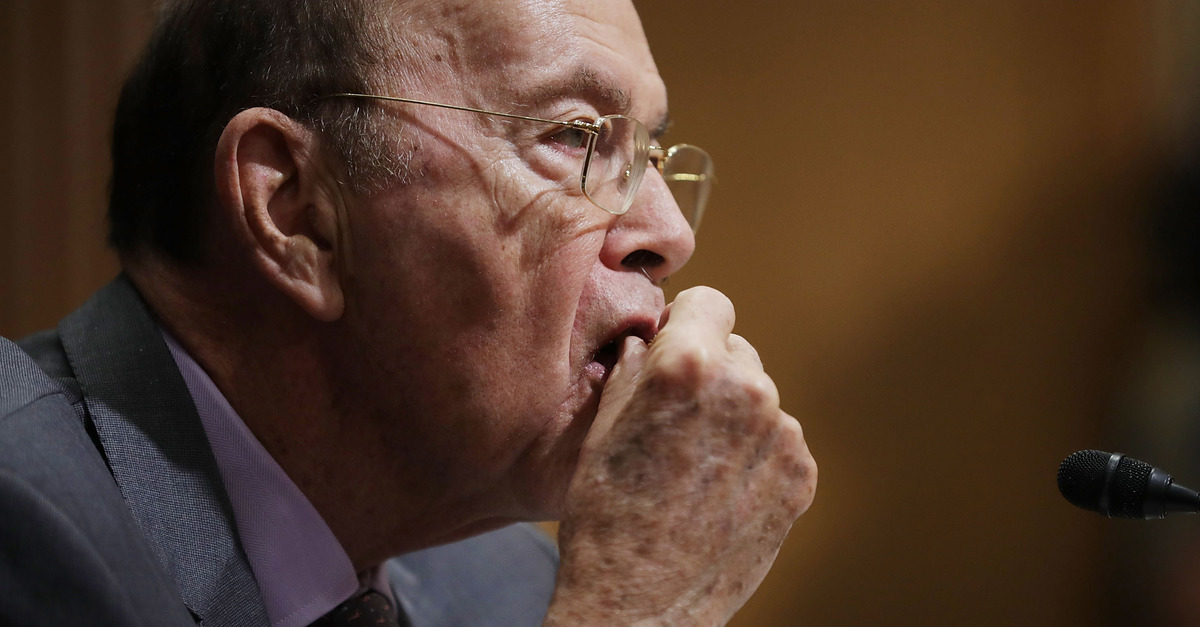

At the center of the census question controversy is Commerce Secretary Wilbur L. Ross. Judge Furman spared no feelings or ink in castigating Ross throughout his Cervantian opinion. Let’s take a look at some of the more interesting ways in which Ross was called out in court.

1. A Charlotte’s Web Reference

The opinion wastes little time in amusingly calling out Ross’s untoward behavior viz. the citizenship question. On page 8, Judge Furman notes:

He failed to consider several important aspects of the problem; alternately ignored, cherry-picked, or badly misconstrued the evidence in the record before him; acted irrationally both in light of that evidence and his own stated decisional criteria; and failed to justify significant departures from past policies and practices — a veritable smorgasbord of classic, clear-cut [Administrative Procedure Act] violations.

The phrase “a veritable smorgasbord” is actually the title of a song written by Richard B. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman for the 1973 Hanna-Barbera animated film adaptation of E.B. White‘s classic coming-of-age farm novel.

2. Ross lied about what he was trying to do.

Judge Furman notes that the commerce secretary’s purported reason for initially seeking to include the citizenship question was “in response to a request from the Department of Justice for better citizenship data to assist in its enforcement of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.” That, however, wasn’t really the case because Justice Department’s request was actually made after Ross had already determined to buck decades of wisdom and precedent and include the question “over the strenuous objections of the Census Bureau itself.”

“[P]erhaps most egregiously, the evidence is clear that Secretary Ross’s rationale was pretextual—that is, that the real reason for his decision was something other than the sole reason he put forward…namely enhancement of DOJ’s VRA enforcement efforts,” Judge Furman notes on page 245. “Secretary Ross had made the decision to add the citizenship question well before DOJ requested its addition in December 2017.”

In fact, an email cited by the court makes it clear that Ross had decided to include the question by August 11, 2017.

3. And then he tried to cover up those lies.

Judge Furman cites several pieces of evidence to document the Commerce Department’s cover-up. Chief among that evidence, on page 100, is testimony that DOJ’s request for the citizenship question was actually only made specifically because Ross personally requested that DOJ make their own request.

Other pieces of evidence include: (1) a “curated and highly sanitized” Administrative Record that “omitted all materials relating to the deliberations and communications of Secretary Ross and his aides prior” to the request from DOJ; (2) “lack of any record…including but not limited to Secretary Ross’s early discussions with other officials regarding addition of the citizenship question”; (3) “failure to disclose…that the issue was on the table prior” to DOJ’s request; (4) “revisions…which were plainly intended to downplay the degree to which Secretary Ross departed from the process ordinarily used to consider new questions on the census”; and (5) “misleading, if not false, statements…that Secretary Ross began considering the issue only after receiving” DOJ’s request.

“Those acts and statements are not the transparent acts and statements one would expect from government officials who have decided, for bona fide and defensible reasons, to change policy,” Furman writes. “Nor are they the acts and statements of government officials who are merely trying to cut through red tape. Instead, they are the acts and statements of officials with something to hide.”

4. Ross had an “unalterably closed mind.”

This passage speaks for itself:

In any event, the evidence summarized above amply supports the conclusion that Secretary Ross did act with an “unalterably closed mind” in that he was “unwilling or unable to rationally consider arguments.” It shows that Secretary Ross had decided to add the question for reasons entirely unrelated to VRA enforcement well before he persuaded DOJ to make its request. And it certainly shows that he was either “unwilling or unable to rationally consider” arguments against the question after he received DOJ’s request, when he was allegedly engaged in the “comprehensive review” that led to his final decision. For one thing, given the extraordinary lengths to which Secretary Ross and his aides went to generate a request for the question, it is hard to imagine he would have been open to putting the brakes on his quest once he had finally succeeded in getting the request he felt he needed. For another, a decision-maker who was fairly and honestly considering the evidence before him would have been more likely to heed the legal obstacles in his path.

5. Ignorance of the law and Constitution

In a previous court filing, Ross cited the landmark Supreme Court case of Trump v. Hawaii in an effort to defend the administration’s attempt to include the citizenship question on the 2020 census questionnaire. Furman explained that case briefly [italics in original]:

[Trump v. Hawaii] held that judicial “inquiry into matters of entry and national security is highly constrained” because “[a]ny rule of constitutional law that would inhibit the flexibility of the President to respond to changing world conditions should be adopted only with the greatest caution.”

The plaintiffs had argued that the Trump administration was acting with “discriminatory animus” that would result in a “discriminatory effect” by including the citizenship question. Under Constitutional law, such a charge leads to a specific and pre-defined form of judicial inquiry that essentially prioritizes the plaintiffs’ accusations. The defendants acknowledged this set of standards but simultaneously trotted out the “travel ban” case in order to argue that the court actually can’t look very hard for evidence of discrimination.

Judge Furman noted that Ross and the other named defendants completely misunderstood that ruling.

“[A]pplying Trump v. Hawaii’s deferential review in this setting would do more than unsettle decades of equal protection jurisprudence; it would decimate that jurisprudence altogether…” the court’s opinion reads. “Under that approach, even ordinary government action motivated ‘in part’ by an unconstitutional discriminatory purpose would survive judicial scrutiny so long as a court could divine some other purpose that may have contributed to the action. That is emphatically not the law.”

[image via Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images]