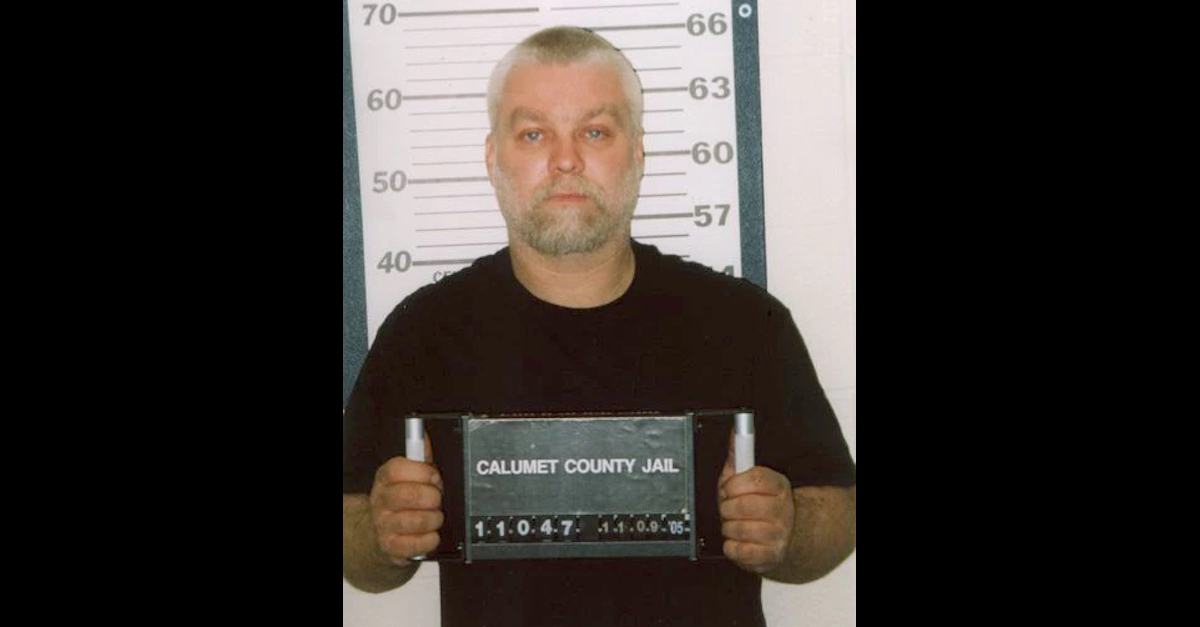

Steven Avery is seen in a 2005 mugshot taken by the Calumet County, Wisconsin jail.

Appellate attorneys for convicted Wisconsin killer Steven Avery on Wednesday filed a 41-page brief with the Wisconsin Supreme Court. The attorneys are asking the high court to review a recent intermediate appellate court decision which dispatched the imprisoned man’s long-standing arguments that he is innocent and that his case deserves an evidentiary hearing to examine new theories about who is responsible for the death of murder victim Teresa Halbach.

Avery became famous after the Netflix series “Making a Murderer” reexamined his March 2007 conviction on charges of intentional homicide and illegal weapons possession.

Avery’s nephew Brendan Dassey was also convicted for being an alleged party to the Halloween Day 2005 killing of Halbach, a freelance photographer. Both men have long proclaimed their innocence; Avery has long articulated that he was set up by various local and state authorities after he filed a wrongful conviction lawsuit in connection with a botched rape case. A jury found Avery guilty of rape in 1985; however, DNA evidence subsequently exonerated him when it pointed to another attacker who by then had been imprisoned for separate offenses.

Avery’s current attorneys, led by Kathleen Zellner of Illinois, are asking Wisconsin’s highest state court to examine three alleged legal errors committed recently by the intermediate Wisconsin Court of Appeals.

First, Zellner wants the Wisconsin Supreme Court to question whether the intermediate court viewed her requests for new evidentiary hearings using an incorrect legal standard.

Second, she wants the high court to answer whether the state “suppress[ed] and with[held]” a compact disc of evidence “for 12 years containing a forensic police report” of evidence she believes points away from Avery and toward one or more of his relatives as Halbach’s possible killers.

Third, Zellner wants the high court to answer whether “a state actor’s destruction of contested evidence” — namely the victim’s alleged bone fragments — occurred “in violation” of a state statute and therefore must count as “evidence of bad faith” under a governing U.S. Supreme Court case and Avery’s right to due process.

Zellner immediately pointed to the popularity of the Avery case as one reason why the Wisconsin Supreme Court should closely examine it:

Mr. Avery’s case has produced an avalanche of coverage on a worldwide stage. It has generated legal commentary that has not been matched in the last 50 years. Law review articles, law school classes, case law, petitions to the White House, and millions of documentary viewers have grappled with one fundamental question: Did Mr. Avery receive a fair trial free of constitutional violations? When Mr. Avery was indigent and unknown, the Wisconsin Courts dismissed his 2013 postconviction motion as lacking any merit and being based on “unsubstantiated claims,” “empty and without substance,” “wildly speculative,” and “contrary to Wisconsin’s long standing law and procedures.”

Zellner indicated that Avery was an “unknown” person in 2013 — that’s two years prior to the December 2015 release of “Making a Murderer” — despite hundreds of hours of television coverage being devoted to the search for Halbach and the subsequent Avery and Dassey cases on at least eight Wisconsin television stations, several radio stations, and a plethora of newspapers in Green Bay, Milwaukee, and elsewhere between 2005 and 2008 and beyond.

She then skewered the intermediate Wisconsin Court of Appeals for — in her view — holding Avery to a “greatly enhanced” standard for re-arguing his case now that he is famous:

Now that Mr. Avery has obtained postconviction counsel and nationally renowned experts, the Court of Appeals has applied a greatly enhanced pleading standard to his § 974.06 motion and has failed to look at the cumulative effect of the ineffective assistance of counsel and Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963) claims. Also, the Court of Appeals has made significant factual errors resulting in an unreasonable application of the facts in its analysis of the bullet and bone evidence which, among other errors, results in its erroneous exercise of discretion in affirming the circuit court’s denial of an evidentiary hearing. Mr. Avery should not be held to a higher standard than other movants. This Court should apply the standards it has so clearly articulated in past cases and allow Mr. Avery to have an evidentiary hearing on the merits of his allegations of constitutional violations. If his conviction truly has integrity, it will withstand the scrutiny of an evidentiary hearing. Without such scrutiny the question of the integrity and fairness of Mr. Avery’s trial hangs like a dark cloud over the Wisconsin judicial system.

“This case presents ‘special and important reasons’ justifying Supreme Court review,” Zellner and her team then argued.

The 41-page legal document goes on to address specific issues in order.

It argues that the Court of Appeals set an “[i]mpossible [s]tandard to [m]eet” with regards to Avery’s claims that his previous attorneys provided “ineffective assistance” during previous proceedings.

“The Court of Appeals, inexplicably, concluded that Mr. Avery could have conducted experiments in his prison cell in Boscobel, 250 miles from the Avery Salvage Yard” where the state has long argued Halbach was murdered, Zellner argued. “Mr. Avery had no more ability to conduct simple experiments than he did to hire nationally renowned experts.”

“This Court should determine whether the Court of Appeals misapplied the legal standard of what a movant must allege for an evidentiary hearing and unreasonably determined facts and misstated facts in the record in denying review,” she also pleaded. “Rather than accepting Mr. Avery’s facts as true, the Court of Appeals disputed the facts and presented its own inaccurate version of the State’s theory in rejecting Mr. Avery’s showing of trial counsel’s ineffectiveness.”

The latter argument is connected to the pleading standard necessary for a court to order an evidentiary hearing in the first place.

“When a lower court’s analysis begins to weigh the evidence (it misstates) and the uncontradicted facts a movant asserts are not taken as true, the need for an evidentiary hearing is apparent,” Zellner later said.

In other words, as a baseline legal concept, appeals courts are supposed to weigh issues of law, not settle which versions of facts are correct.

Later, Zellner renewed arguments that bone fragments said to have been discovered in a Manitowoc County gravel pit — a pit owned by the same county whose law enforcement agents Avery was suing over his 1985 wrongful conviction — were “released” to the Halbach family in violation of state evidence laws and “without notice” to Avery. Zellner wanted access to the bones from the gravel pit for additional testing to determine whether they were indeed Halbach’s and whether or not they might yield the DNA of Halbach’s killer.

Zellner and Avery have long argued that other bones which turned up closer to Avery’s trailer were planted — perhaps by overzealous authorities who were myopically focused on Avery and driven by their alleged vendettas against him in connection with the civil suit. The quarry was near the salvage yard where Avery and other members of his family lived in separate trailers.

In her Wednesday argument, Zellner asserted that the state’s violation of its own evidence preservation statute should be considered bad faith under controlling U.S. Supreme Court precedent — thus necessitating an evidentiary hearing for Avery and ultimately — potentially — a new trial to sort out his guilt or innocence. Zellner explains this point at length (emphasis in original):

The State went to great lengths [at trial] to confine the murder to the Avery property and to one person because it made its case against Mr. Avery much easier. It is here where the exculpatory value of bone fragment evidence lies: Mr. Avery was tried and convicted on a theory that (1) he alone killed and burned Halbach in his burn pit; (2) after burning Halbach in his burn pit, [he] must inexplicably have moved her bones over to the Dassey burn barrel; and (3) that the suspected human bones found in the Manitowoc gravel pit—not on the Avery property—simply “[we]re really not evidence” precisely because they could not be identified through DNA testing to be human or Halbach’s.

Zellner continues (again, emphasis in original):

The Court of Appeals overlooked that Mr. Avery was found not guilty of mutilation of a corpse. It reasoned, “The apparent thrust of Avery’s claim is that, if Halbach’s bones were found in the Gravel Pit, then she was killed by someone else. As Avery never explains why he himself would have been unable to dispose of Halbach’s remains in the gravel pit, this line of reasoning is wholly speculative.” The very obvious explanation for why Mr. Avery would have been unable to burn Halbach in his burn pit and then transport her remains to the Gravel Pit for purposes of the court’s hypothetical, is that Mr. Avery was acquitted of burning Halbach’s body in his burn pit, or burning or mutilating Halbach’s body at all. This gross misunderstanding of the facts caused the Court of Appeals to start from a premise not supported by the record that Mr. Avery is responsible for taking the bones to the Gravel Pit. His jury decided just the opposite. It is undisputed that Halbach’s body was mutilated after her death; the potential to inculpate another person for the mutilation of Halbach’s body, for which Mr. Avery was acquitted, is strong.

In several locations, Zellner fought back at misunderstandings and mistakes about the factual record which crept into the intermediate appellate court’s recent opinion.

“The Court of Appeals erred in asserting that human bone fragments were discovered in Mr. Avery’s burn barrel,” Zellner wrote in a footnote. “The bones were discovered in the Dassey burn barrel.”

Law&Crime’s previous coverage of the intermediate Court of Appeals decision which jettisoned Avery’s appeal is here.

Read the entire document below:

[Editor’s note: most legal citations in the above quotes have been omitted for ease of reading. The full quotes appear in the embedded document, with citations.]