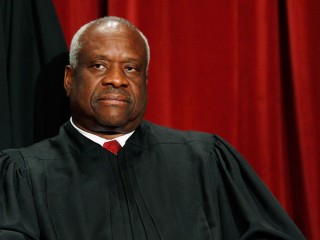

I get the sentiment. Thomas has made willful blindness the cornerstone of his jurisprudence, and in doing so, has probably done far more to widen the chasm between the races than narrow it. And of course, there is more than a little evidence that Thomas might have sexually harassed a woman. Including Thomas in a Smithsonian exhibit would be a great honor, so excluding him should amount to a fitting insult, right? Not in my book.

In its own words, the Smithsonian described the museum as follows:

“The National Museum of African American History and Culture is the only national museum devoted exclusively to the documentation of African American life, history, and culture. It was established by Act of Congress in 2003, following decades of efforts to promote and highlight the contributions of African Americans.There are four pillars upon which the NMAAHC stands:

- It provides an opportunity for those who are interested in African American culture to explore and revel in this history through interactive exhibitions

- It helps all Americans see how their stories, their histories, and their cultures are shaped and informed by global influences

- It explores what it means to be an American and share how American values like resiliency, optimism, and spirituality are reflected in African American history and culture

- It serves as a place of collaboration that reaches beyond Washington, D.C. to engage new audiences and to work with the myriad of museums and educational institutions that have explored and preserved this important history well before this museum was created.

The NMAAHC is a public institution open to all, where anyone is welcome to participate, collaborate, and learn more about African American history and culture. In the words of Lonnie G. Bunch III, founding director of the Museum, “there are few things as powerful and as important as a people, as a nation that is steeped in its history.”

The Smithsonian committed to exploring “what it means to be an American” and how American values are “reflected in African American history and culture.” There is no rational basis for any conclusion that a black man serving at the highest level of government for twenty-five years is not crucial to the telling of that history. For starters, Clarence Thomas as black jurist is a symbol as much as he is a man. Discrimination is shallow, based on surface differences between the races – committed without regard for the political views of its victims. On that basis, the fact that Clarence Thomas’ skin color didn’t prevent him from attaining the nation’s highest bench is independently significant – regardless of any sins he committed once he reached it.

Black Americans on all ends of the political spectrum can and should rejoice having one of their own reach such heights; if that joy is tempered by a disdain for Thomas’ attitude toward his own race, we will have succeeded in giving black history the complex dimension it deserves. Thomas’ misguided conservative views and many appalling opinions fail to disqualify him from taking his rightful place in the annals of African American history. Like it or not, this man was there. He made history both as its subject, and as its architect. He succeeded despite his beliefs as well as because of them. As our world has become increasingly aware of the subtle effects of discrimination, we have seen the erroneous whitewashing of history. Racial, ethnic, and religious minorities, women, and other disadvantaged groups are chronically absent from the telling of the American story. The suppression of those stories isn’t wrong simply because it hurts minority groups; it’s wrong because it’s inaccurate. African-American history isn’t a direct path in which every individual began in oppression and ended in nobility; it’s a meandering maze that is every bit as complex as the history of any other people. Clarence Thomas’ ideology may be a grotesque mutation of Booker T. Washington’s teachings, but its existence isn’t any less powerful for its wrongness.

And then there’s Anita Hill—likely the real reason why the Smithsonian curators excluded Justice Thomas. I have nothing but sympathy for this courageous woman who was thrust into the national spotlight against her will and to her great personal detriment. Professor Hill’s story is inextricable from that of her former boss, and absolutely requires inclusion in this museum; but including Anita Hill without Clarence Thomas just doesn’t work. If the museum excluded Thomas as a show of solidarity for victims of sexual harassment, it may have unwittingly harmed the very cause it tried to champion. Victims of sexual harassment, in particular, often feel invisible and voiceless. The public is slow to believe them, and the legal system is even slower to bring them justice. Those who are victimized by powerful and successful men are routinely silenced, even when those in proximity are clear that the victim is credible. A choice to mute references to Clarence Thomas is one that allows students of history to forget the story Thomas created. It may be uncomfortable to laud a black man’s ascent to the Supreme Court while simultaneously condemning him – but ultimately, such honesty is the obligation of the tellers of history.

The Smithsonian, in its well-meaning, but poorly-considered gesture missed part of the point entirely. Our rule cannot be that persons of color are only relevant when they are perfect or when their actions are heroic. No telling of American history would be complete without reference to the damage done by Richard Nixon, Antonin Scalia, Strom Thurman, or even Donald Trump. The Smithsonian’s job was to include Justice Thomas in its museum; what his legacy will be, though, is entirely up to Clarence Thomas himself.

—

This is an opinion piece. The views expressed here are just those of the author.

Follow Elura on Twitter @elurananos