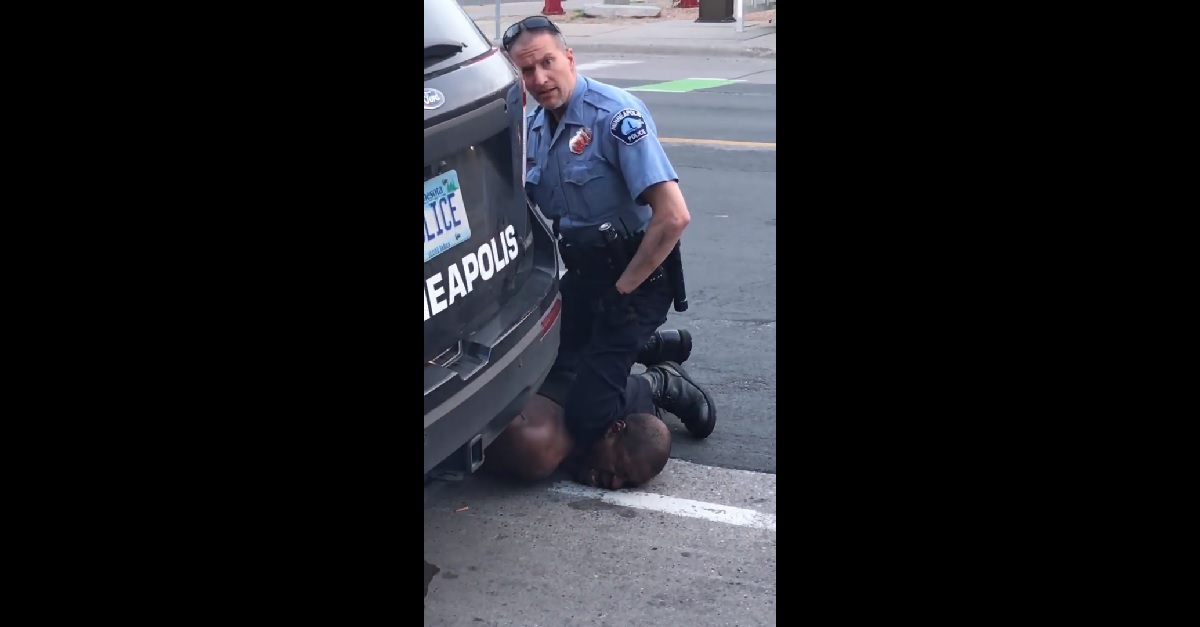

Prosecutors in Hennepin County, Minnesota are on both official and unofficial notice: scores of people want the officers involved with George Floyd‘s arrest and final moments charged with murder. One officer, Derek Chauvin, pressed his knee to Floyd’s neck for an excruciatingly long time as Floyd struggled in agony to say he could not breathe. The Minneapolis Police Department says Floyd died shortly later after being transported by ambulance from the scene.

Floyd’s family initially asked for murder charges; they later asked for the death penalty. (Minnesota does not have a death penalty.) Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey said he told prosecutors he wanted charges filed. Attorney Benjamin Crump is calling the death a murder. A chorus of uncountable numbers on Twitter has also called the death a murder. Taken collectively, all of these people want charges filed immediately. As of press time, none of the officers have been arrested or charged.

“Murder,” however, is a legally operative word. Minnesota law contains three separate possible murder charges; the question now, assuming prosecutors are mulling their options, is which path they may choose to pursue. What follows below is an explanation of the different legal options available in the Floyd case and a collection of opinions from criminal defense attorneys, most of whom are former prosecutors, as to the likely deliberations occurring in the Minnesota offices tasked with examining it. All of the attorneys quoted are hosts or frequent guests on the Law&Crime Network. Though they disagreed somewhat as to which charges might best fit the facts of the case, they all seemed to agree that a rush to judgment by prosecutors could result in a legal disaster for the state.

The Law

First-degree murder in Minnesota requires prosecutors to prove that a killer acted with premeditation and with the “intent to effect the death” of another person. “Premeditation means to consider, plan or prepare for, or determine to commit, the act” of murder. First-degree murder carries a life sentence.

Second-degree murder requires prosecutors to prove intent, but not premeditation. It is punishable by up to 40 years in prison.

Third-degree murder requires neither premeditation nor intent. It merely requires prosecutors to prove that a defendant “causes the death of another by perpetrating an act eminently dangerous to others and evincing a depraved mind, without regard for human life.” It is punishable by up to 25 years in prison.

There are two lesser manslaughter charges on the books would could give prosecutors other options.

The Debate

High-profile criminal defense attorney Linda Kenney Baden, who is also a former prosecutor, says authorities are likely waiting for an official cause of death before deciding precisely who to charge with what. Four officers, after all, were present and involved to varying degrees.

“The prosecutor needs to determine” precisely how Floyd died, Baden said, because while Chauvin, the officer identified has having his knee to Floyd’s neck, may not have been the primary cause of Floyd’s death. While Chauvin’s conduct “looks more egregious to the cause of death,” it may not have been “the effective cause of death,” Baden noted. Prosecutors must narrow down who was responsible for what, specifically, before they move forward — assuming prosecutors are going to file charges.

“The compression from the middle cop preventing [Floyd’s] chest from being able to inhale and exhale probably is the effective cause” of death, Baden posited. The “neck compression” played a role but perhaps was not the primary cause of death. Baden believes Floyd likely died at the scene but wasn’t officially pronounced dead until he arrived at the hospital.

Baden believes third-degree murder is the most likely charge. Baden called Floyd’s cries to his mother “heartbreaking” and said she was strongly moved by Floyd’s decision to call the officers “sir” until he lost consciousness and possibly died on the street.

“In my opinion,” Baden concluded, “they were acting with depraved minds, in concert . . . showing the community [the bystanders] what can be done to them by making an example of Floyd.”

New Jersey criminal defense attorney Mike Koribanics, also a former prosecutor, believes authorities might have strong showing for a more serious charge.

“I think they’re going to go for highest charge: first-degree, premeditated murder,” Koribanics opined. “They’re going to have to strategically go for that” and then give the jury in any hypothetical prosecution a chance to convict on the lesser charges.”

“I think there’s a very strong case for intent,” Koribanics said; he suspects prosecutors will, if they move forward, call an expert witness on police brutality to make the argument that what occurred to Floyd was far beyond the reasonable use of restraint in an arrest situation.

“Here, there is direct video evidence of Floyd complaining of suffocation. It was well known a potential death could result. Even the bystanders with no connection to the police department are going to testify they heard this, saw this, and that the officers did nothing.” That, Koribanics believes, could prove intent, if not premeditation.

Koribanics also said the sum total of the procedure used by the officers reminded him of so-called “hog tying” by police (where a suspect is handcuffed behind the back and an officer presses his knee into the suspect’s back). Such tactics have been litigated previously.

Koribanics cautioned that any prosecutor who files a case too quickly is setting the public up for a possible failure.

“They [prosecutors] want to make very sure their presentation to the grand jury is as solid as can be; they are waiting to ensure they’re not being accused of a rush to judgment,” Koribanics said. “When making an arrest in a high profile case, you want to make sure your probable cause is very strong.”

Otherwise, the state may have to put witnesses on the stand in a probable cause hearing before all the discovery has been collected — and that can backfire, Koribanics explained. He noted that the procedure is oftentimes highly dependent on rules which differ from state to state; Koribanics does not practice in Minnesota, but there are parallels everywhere.

“It goes back to the old adage of prosecution: slow and steady wins the race,” he said. “They have to maintain their dedication to the law and their presentation of the case, keep their eye on where it’s going, and proceed slowly, steadily, and thoroughly to ensure any conviction sticks” though any inevitable appeals process.

Koribanics also noted that there may be jockeying between federal and state law enforcement agencies; the FBI is already involved in the case, and federal charges would be separate from state charges.

Attorney Brian Buckmire is a New York public defender. He said that a first-degree murder conviction requires the state to show that after the defendant formed an “intent to kill, some appreciable time passed during which the consideration, planning, preparation or determination required by Minn. Stat. § 609.18 prior to the commission of the act took place,” quoting a Minnesota Supreme Court case. Another case further defines premeditation as “preexisting reflection and deliberation involving more than mere intent to kill; it must be inferred from totality of circumstances, and need not involve extensive planning and calculated deliberation, and requisite plan can be formulated virtually instantaneously.” Yet another explains that evidence relevant to these determinations “includes [the] defendant’s actions before, during, and after the killing, the number of wounds inflicted, infliction of wounds to vital areas, infliction of gunshot wounds from close range, and passage of time between infliction of wounds.”

“I think the prosecution has an argument that Chauvin caused Floyd to pass out,” Buckmire opined. “Then, by the nature of Chauvin continuing to apply pressure to Floyds, neck, Chauvin afterwards killed Floyd. This is going to depend on the medical examiner’s report, but the report from the fire department that helped EMS in the ambulance says Floyd was ‘pulseless’ would suggest that the officer killed Floyd. Maybe they argue his intent went from subduing to murder once Floyd passed out.”

New York criminal defense attorney Julie Rendelman, also a former prosecutor, agreed that prosecutors are probably waiting for an autopsy before deciding who might be charged with what. “While we await an autopsy to determine the exact cause of death, there can be no question that anybody who watches this video for even a moment would recognize that forcefully placing your knee on an individual’s neck as they lay prone on the ground begging to breathe is the definition of depraved indifference to human life,” Rendelman said. “Add three minutes, five minutes, seven minutes of continuous pressure to the neck area, even as Mr. Floyd appears in severe distress, and perhaps there is an argument that the officer’s acts have risen to the level of intentional murder.”

Former federal prosecutor Gene Rossi, who is now in private practice, thought a first-degree murder charge would be difficult for prosecutors to win.

“Premeditation would be hard,” he said. However, “I think manslaughter is a Michael Jordan layup.” In other words, it’s something in between: “third-degree fits.” Rossi didn’t mince words for the other officers involved, suggesting at a minimum that they could likely be charged “as an aider and abetter, if not a conspirator.”

“The video shows at best a callous disregard for human life and for their roles as police officers keeping the peace,” Rossi said. “I always tried to charge conspiracy as the main count, if the evidence suggests such. If not, multiple officers can be charged as aiders and abettors to [Chauvin]. [Chauvin] is surely susceptible to a manslaughter charge—which might be the plea offer along with a stiff sentence—but he also fits the third degree charge as Linda [Kennedy Baden] has suggested.”

“As for second degree or premeditated, because they are officers of the law, a jury may find it extremely difficult to prove such a higher intent,” Rossi said, echoing jury verdicts in a number of other cases where officers have been charged with crimes. “However, if the prosecutors can find racial animus in the behavior of [Chauvin] and [the] others, then you could have a situation where the Justice Department could bring federal charges like they did in the Rodney King matter in the 1990s.”

Again, as of press time, none of the officers involved have been charged with a crime. However, the above debates illuminate the likely conversations occurring in prosecutors’ offices this week in Minnesota about what, if any, charges could be brought.

[Image via YouTube screengrab]