Pedro Hernandez showed no reaction as jurors delivered their verdict. Another jury had deadlocked following 18 days of deliberation in 2015, leading to a retrial that spanned more than three months. Hernandez, who once worked in a convenience store in Etan’s neighborhood, had confessed, but his lawyers said his admissions were the false imaginings of a mentally ill man.

This time, the jury deliberated over nine days before finding Hernandez, 56, guilty of murder during a kidnapping in a case that shaped both parenting and law enforcement practices in the United States.

Some of the jurors from the first trial attended the second one, and several of them wept Tuesday as the verdict was read. The slain boy’s father, Stan Patz, was being comforted by the ex-jurors and appeared to wipe tears from his eyes.

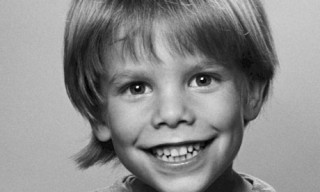

The Patz family and authorities may never know exactly what became of the boy. No trace of him has been found since the May day he vanished, on the first day he got the grown-up privilege of walking alone to the bus stop about two blocks away in a then-edgy but neighborly part of lower Manhattan.

Etan became one of the first missing children ever pictured on milk cartons, and the anniversary of his disappearance has been designated National Missing Children’s Day. His parents lent their voices to a campaign to make missing children a national cause, and it fueled laws that established a national hotline and made it easier for law enforcement agencies to share information about vanished youngsters.

And his disappearance helped tilt parenting to more protectiveness in a nation where many families had felt comfortable letting children play and roam in their neighborhoods alone.

“It’s a cautionary tale, a defining moment, a loss of innocence,” Manhattan Assistant District Attorney Joan Illuzzi said in an opening statement. “It is Etan who will forever symbolize the loss of that innocence.”

The decadeslong investigation took investigators as far as Israel, but Hernandez wasn’t a suspect until 2012, when renewed news coverage of the case prompted a brother-in-law to tell police that Hernandez had told a prayer group decades earlier that he’d killed a child in New York. Authorities would later learn that he’d made similar, if not entirely consistent, remarks to a friend and his ex-wife in the early years after Etan vanished.

After police finally came to Hernandez’ Maple Shade, New Jersey, door, he confessed, saying he’d offered Etan a soda to get him into the store basement, choked him, put him — still alive — in a box and left it with a pile of curbside trash.

“Something just took over me,” Hernandez said in one of a series of recorded confessions to police and prosecutors. He said he’d wanted to tell someone, “but I didn’t know how to do it. I felt so sorry.”

Prosecutors cast his confession as the chillingly believable words of a man unburdening himself, and they argued it was buttressed by the less specific admissions he’d made earlier to his relatives and acquaintances.

Defense lawyers and doctors portrayed Hernandez as man with psychological problems and intellectual limitations that made him struggle to tell reality from fantasy — and made him susceptible to confessing falsely after more than six hours of questioning before recording began. His daughter testified that he talked about seeing visions of angels and demons and once watered a dead tree branch, believing it would grow.

“Pedro Hernandez is an odd, limited and vulnerable man,” defense lawyer Harvey Fishbein said in his closing argument. “Pedro Hernandez is an innocent man.”

Prosecutors have suggested Hernandez faked or exaggerated his symptoms.

Defense lawyers also pointed to a different man who was long the prime suspect — a convicted Pennsylvania child molester who made incriminating remarks about Etan’s case in the 1990s and who had dated a woman acquainted with the Patzes. He was never charged and denies killing Etan.

This article was written by COLLEEN LONG, The Associated Press.