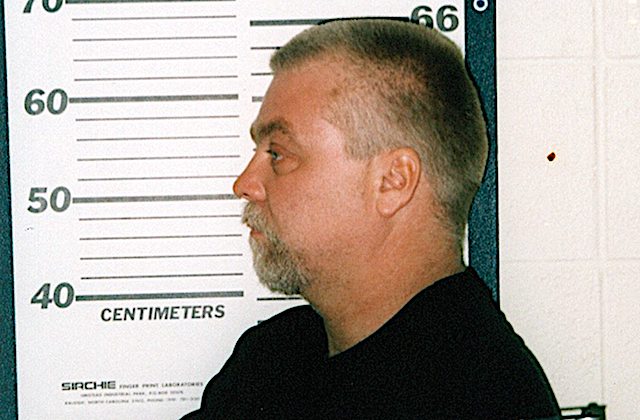

The lead post-conviction attorney for Making a Murderer subject Steven Avery has recently put forth another new theory on what may have happened to murder victim Teresa Halbach.

Kathleen Zellner, who began representing Avery after the hit Netflix documentary caused a worldwide stir, is now focusing attention on violent pornographic material and images of Halbach investigators discovered on a computer retrieved from the home of Avery’s nephew and co-defendant Brendan Dassey.

Zellner’s allegations about the computer are contained in a public court document which asks a local trial judge in Manitowoc County, Wisconsin, to reconsider a previous decision refusing to grant Avery a new trial. The motion to reconsider was filed October 23, 2017.

Some of Zellner’s most serious assertions appear to twist and omit critical facts, some of which she failed to acknowledge in either the October 23, 2017 motion or a follow-up supplement filed October 31, 2017.

The omitted facts might, in theory, implicate her own client in the Halbach murder, a LawNewz analysis has found.

Here, we examine those additional facts.

The Halbach Images

In her motion to reconsider, Zellner states:

[T]he Dassey computer contains images of Ms. Halbach, violent pornography and dead bodies of young females viewed by Bobby Dassey at relevant time periods before and after the murder of Ms. Halbach. (Page 3.)

The problem with this assertion is that it grammatically leads to the conclusion that the various types of images, including the images of Halbach, were searched both before and after Halbach’s murder. If that is true, it is a bombshell. We know Halbach had been to the Avery family property on previous photographic assignments. Evidence that someone on the property was searching for Halbach online or viewing Halbach’s photo would suggest Halbach was deliberately targeted by someone with access to the Dassey computer.

The problem for Zellner is that her own computer expert’s attached affidavit directly refutes her assertion about the timing of the Halbach photos. With regards to the two photos of Halbach, the expert states:

“Since the files were recovered via data carving, there is no file system metadata available. The files’ original path, file name, and created, accessed, or modified timestamps are not available, nor is there any information regarding how they arrived on the computer.”

Additionally, Special Agent Tom Fassbender’s original report on the computer states the images of Halbach were believed to have been saved April 18, 2006, based on an initial law enforcement examination of the computer that year.

Portaits of Halbach, including and similar to those found on the Dassey computer, were widely disseminated on the Web sites of Wisconsin news organizations beginning on the evening of November 3, 2005, the date Halbach’s family reported her missing. It is possible both images ended up on the computer when someone used it to read a news article about the case, though Zellner’s motion does not hint at that possiblity.

It seems there is no evidence the images of Halbach were accessed by someone using the Dassey computer before the crime. Zellner’s failure to explicitly state that creates confusion (at best) or misleads the court (at worst).

Images of Violent Pornography

In addition to the portraits of Halbach, Zellner argues the computer contained images of “violent pornography,” the “dead bodies of young females,” “young females being raped and tortured,” “images of injuries to females,” “a decapitated head, bloodied torso, a bloody head injury and a mutilated body.” The images of the women bear an “uncanny resemblance” to Halbach, Zellner argues. A number of the images are attached as exhibits to her October 23, 2017 motion.

Documents filed by Zellner state that the sexually-explicit searches occurred on “various dates,” though September 18, 2005 is the only date listed. (The expert’s own cover page incorrectly lists the date as September 18, 2006.) That 2005 date is 43 days before Halbach’s October 31st murder and 52 days before Avery’s November 9th arrest.

The images said to have been found on the computer carry the dates of April 9, 2006, and April 19, 2006. It is unclear if the images which contain 2006 dates could have been searched and downloaded on the 2005 date.

These dates are troublesome for Zellner’s thesis.

Implicating Bobby Dassey

Zellner’s motion accuses Bobby Dassey, the brother of Avery’s nephew Brendan Dassey, of searching for the sexual and violent images.

Zellner’s October 23, 2017 motion argues the following:

“These searches have been isolated to times when only Bobby Dassey was home . . . [a]lthough there was only one user account . . . the relevant searches occurred during times when Bobby Dassey was alone in the house.” (Pages 46-47.)

Zellner supports her claim by stating:

“While Bobby worked nights and was home during the day on weekdays, all of his family members either attended high school or worked the day shift.” (Page 47; emphasis added on the word “weekdays.”)

The first problem with Zellner’s assertion is that the given date of the offending searches is September 18, 2005, a Sunday, as at least one online commenter was quick to point out. Additionally, the date many of the other images were said to have appeared, April 9, 2006, was also a Sunday. The third date the offending images were said to have appeared, April 19, 2006, was a Wednesday. If pornographic images were searched, viewed, or downloaded on any different dates, the precise other dates do not appear in Zellner’s motion or the attached affidavits.

If we are to trust all three dates, that two of the offending searches occurred on Sundays destroys Zellner’s theory that Bobby Dassey was the “only” one home when the searches could have occurred because everyone else was gone during the day on “weekdays.”

Plus, the list of searches from September 18, 2005, contains searches between 5:57 a.m. and 6:05 a.m., and then again from 7:52 p.m. and 10:04 p.m. Those searches did not occur “during the day,” as Zellner asserts.

The second problem with Zellner’s assertion is that it fails to address the probability that the various Avery family members may have likely had relatively wide-open access to one another’s homes, which were situated together on the family’s salvage lot. Many of the Avery family members worked the salvage lot during the day.

Still, Zellner not only argues that Bobby Dassey was probably responsible for the searches, but goes on to supply the court with an affidavit from police procedure expert and former FBI agent Gregg McCrary to assert that:

“It is my opinion . . . that Bobby Dassey’s internet searches reflects a co-morbidity of sexual paraphilias. The sexual and violent content he was searching for and viewing should have alerted investigators to Bobby Dassey as a possible perpetrator of Teresa Halbach’s murder.”

[ . . . ]

“Bobby Dassey was becoming obsessively deviant in his viewing of violent pornography . . . Bobby Dassey’s entanglement in the investigation into the murder of Teresa Halbach should have alerted the investigators to Bobby Dassey as someone having an elevated risk to perpetuate a sexually motivated violent crime such as the violent crime perpetrated on Teresa Halbach.”

“Obsessively deviant”? Those are mighty strong words for people who can’t admit that Sunday is not a weekday.

McCrary’s affidavit states that he named Bobby Dassey because:

“I was provided with a graph prepared by Kathleen T. Zellner & Associates . . . [t]he graph illustrates the timeline of the pornographic searches and, based upon other evidence, restricts this computer activity to Bobby Dassey.”

In the affidavit, it’s clear that Zellner, not her expert, connected Bobby Dassey to the pornography. In Zellner’s motion, Zellner cites her expert’s affidavit as the source of the connection. (Page 46-47.)

That might, arguably, be a sleight-of-hand.

Indeed, in a supplemental motion filed October 31, 2017, Zellner provides a transcript of a conversation between Steven Avery and Barb Tadych, Bobby Dassey’s mother:

Steven Avery: Bobby’s home.

Barb Tadych: He wasn’t always home.

Steven Avery: Well, you — well, most of the time he was home.

Barb Tadych: No.

Plus, in the original April 21, 2006 warrant for the computer, investigators noted that the computer was in Blaine Dassey’s bedroom, not Bobby’s. Blaine is another Dassey brother. Co-defendant Brendan Dassey oftentimes used the computer according to other witnesses interviewed by investigators.

In the prison call noted above, Barb Tadych denies even having Internet access on her home computer, a claim Zellner calls “unequivocally false.” In the original April 21, 2006 search warrant, investigators mention a recorded jailhouse phone call between Barb Tadych and her son, co-defendant Brendan Dassey. She told Brendan he probably received a busy signal earlier because Blaine was “probably on the computer.”

The logical loops involving the dates of the searches and the levels of access of the various family members make it hard to definitively conclude that Bobby Dassey was the person responsible for the searches.

The Hidden Links To Steven Avery

Zellner’s argument conveniently — and strikingly — avoids the fact that her own client, Steven Avery, is said to have provided some of the information which led investigators to the Dassey computer in the first place.

That link is critical, yet Zellner neither admits nor explores the connection in her October 23, 2017 motion or affidavits, nor does she explore it in her October 31, 2017 supplement.

A motion originally filed under seal by Steven Avery’s trial attorneys provides the link between Steven Avery himself and the Dassey computer. It is now unsealed and in the public record.

That motion, dated June 16, 2006, complains that another jail inmate named Orville O. Jacobs may have been placed in a jail cell near Avery’s in an attempt to glean information from Avery. Avery’s trial attorneys, Dean Strang and Jerry Buting, struggled to even determine why Jacobs was in jail in the first place, since they could not at the time locate records in a state database stating why Jacobs had been arrested.

Attached to the June 16, 2006 Strang/Buting motion is a police report which outlines a purported conversation between inmates Jacobs and Avery:

“STEVEN [Avery] also told ORVILLE [Jacobs] his sister, BARBARA, has porn on her computer and if it was ever found, there would also be trouble.”

Avery’s sister Barbara is now Barb Tadych, Bobby and Brendan Dassey’s mother.

Also attached to the motion is a handwritten, signed statement from Orville O. Jacobs:

“Steve [Avery] told me his sister Barbara has porn stuff on her computer and that if it is found they would be in trouble.”

The documents which detail the contact between Orville O. Jacobs and the authorities indicate that Jacobs spoke with his jailers on April 12, 2006 and with Halbach murder investigators Mark Wiegert and Tom Fassbender on April 14, 2006. (Brendan Dassey had been arrested a little more than a month earlier, on March 1, 2006.)

Wiegert and Fassbender obtained a warrant and immediately seized the Dassey computer one week later, on April 21, 2006.

Fassbender applied for the warrant. His application for the warrant cites interviews with Avery family members regarding Brendan Dassey’s screen names and online chats. Fassbender wanted to see what those online conversations contained. The application, however, also seeks material similar to what the Orville O. Jacobs conversations suggested would be on the computer. Fassbender said investigators were looking for “sexually explicit material including, but not limited to, images, records and messages.”

Once the investigators took the computer, they turned it over to the Grand Chute Police Department in neighboring Outagamie County for a forensic analysis on April 22, 2006, the day after it was seized. (Grand Chute performed most law enforcement computer examinations in northeastern Wisconsin around that time.) On May 11, 2006, Grand Chute provided the Halbach murder investigators with a report on the computer’s contents.

Investigators initially appeared more concerned with instant messages back and forth between Brendan Dassey and others than they were with any pornography found on the device.

The Bottom Line

The bottom line is that the dates make it impossible for either Steven Avery or Brendan Dassey to have any connection to the images allegedly viewed on either April 9, 2006, or April 19, 2006. Avery had been in jail since November 9, 2005, and Dassey had been in jail March 1, 2006.

Yet the bothersome chain of events surrounding the Jacobs tip strongly suggests Avery knew about the pornography on the Dassey computer, likely from the late September 2005 date which preceded Halbach’s murder.

Zellner’s motion completely fails to acknowledge the Jacobs documents, ignores that Avery was apparently the first one to talk about the pornography, and ignores the arguments which logically flow from it.

It’s at least arguable that because Steven Avery knew about the pornography, he was either present to view it or conducted the searches himself.

Indeed, there is tangential support for Avery’s appetite for pornography. We know from pretrial hearing transcripts that a substantial cache of pornography was recovered from Avery’s own trailer days after Halbach disappeared. That detail never made it into the trial. Pretrial hearing transcripts also indicate that the state believed Avery had talked to inmates during his 1985 rape incarceration about getting out of prison and building a torture chamber. Avery trial attorneys Buting and Strang argued that the tip about the torture chamber was too ridiculous to believe.

When inmates rat out other inmates, the information usually is, and rightfully should be, considered suspect. Inmates are always throwing one another under the bus in attempts to curry favor with guards, prosecutors, juries, and judges.

Here, however, it is striking that precisely the sort of trouble Avery is said to have predicted with relation to the Dassey computer has, indeed, occurred. Yet Avery’s own purported knowledge of the trouble is eerily missing from his attorney’s motion which accuses nephew Bobby of malfeasance.

Another possible — and logical — argument is this one: Avery knew about the Dassey computer. Avery’s jailhouse statement helped lead criminal investigators to the computer. The computer contained precisely what Avery purportedly said it would contain. Many of the violent pornography searches occurred before Avery’s arrest. Avery lived and worked yards from the Dassey home and probably had access to it. Avery had a trove of pornography in his own trailer. Arguably, then, Avery either viewed or downloaded the pornography himself (perhaps alone, perhaps with others). Therefore, Zellner’s hand-picked expert, on the full set of facts, ought to be able to accuse her own client of being a sexual deviant who fixated on murderous, pornographic images bearing an uncanny resemblance to Halbach.

Why has that argument not been made? Because Zellner’s motion, its attached affidavits, its supplement, and the information she provided her to own experts all collectively failed to include all the facts.

Aaron Keller is an attorney and live streaming trial host for the LawNewz Network. As a former local journalist in Wisconsin, he covered the 2005 Halbach disappearance and the subsequent trials of Avery and Dassey.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]