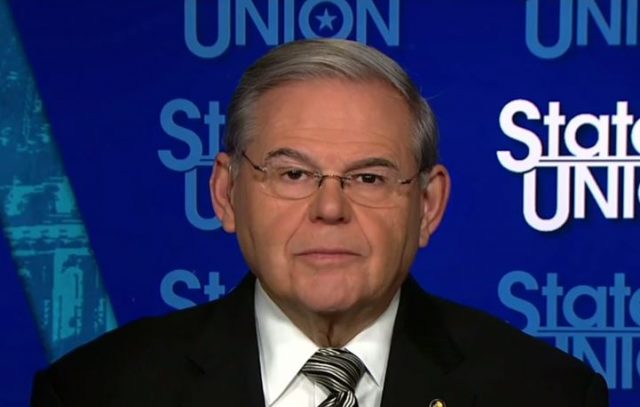

It’s the question at the center of the corruption trial of U.S. Sen. Bob Menendez, D-N.J., and a Florida eye doctor that starts Wednesday in Newark and promises to put the very business of governing under a microscope.

Menendez and Florida ophthalmologist Dr. Salomon Melgen are charged with a conspiracy in which, prosecutors say, Menendez lobbied for Melgen’s business interests in exchange for political donations and gifts that included luxury vacations, flights on Melgen’s plane and stays at his private villa in an exclusive Dominican Republic resort frequented by celebrities including Beyonce and Jay-Z.

The indictment also alleges Menendez pressured State Department officials to give visas to three young women described as Melgen’s girlfriends.

The men both pleaded not guilty, and Menendez has vehemently denied the allegations. Defense lawyers say that the trips described as bribes were examples of friends vacationing together, that most of Melgen’s contributions went to committees Menendez didn’t control and that he didn’t control the people he lobbied on Melgen’s behalf.

“I’m looking forward to finally having the opportunity to seek exoneration,” Menendez said recently. “I do believe we’ll be exonerated. I did nothing wrong, and I did nothing illegal.”

Menendez is up for re-election next year. If he is convicted and steps down or is forced out of the Senate by a two-thirds majority vote before Gov. Chris Christie leaves office Jan. 16, the Republican governor would pick a successor.

While a Democrat has a large polling and financial advantage in November’s election to replace Christie, the stakes are high. A Republican-led partial repeal of the Affordable Care Act might have succeeded this summer if Menendez’s seat had flipped before then.

Among the gifts prosecutors say Melgen gave Menendez were flights on Melgen’s private jet, vacations at Melgen’s private villa in the Dominican Republic and a three-night stay at a luxury Paris hotel valued at nearly $5,000.

Melgen also directed more than $750,000 in campaign contributions to entities that supported Menendez, according to the indictment, which alleges they were inducements to get Menendez to use his influence on Melgen’s behalf.

Prosecutors say that lobbying included a three-year effort to help Melgen avoid paying $8.9 million for overbilling Medicare, a meeting with an assistant secretary of state to help Melgen in a contract dispute over port screening equipment in the Dominican Republic, and helping one of Melgen’s girlfriends and her sister get into the country after their visas were denied.

Melgen’s sentencing in a separate Medicare fraud case has been delayed until after his trial with Menendez.

Jurors will have to wade through complex legal concepts, including whether Menendez’s interactions with executive branch officials were “official acts” as defined under federal bribery statutes. That will depend on how a 2016 U.S. Supreme Court decision reversing the bribery conviction of former Virginia Gov. Bob McDonnell, a Republican, is interpreted.

“This is not a black-and-white area of the law even for people who do this on a regular basis,” said Mala Ahuja Harker, a former federal prosecutor in New Jersey now working in private practice. “I think people’s gut sense of fairness is going to come into play: Does this offend their sense of the way politics is supposed to operate?”

Menendez has hardly been a shrinking violet since his April 2015 indictment, and he has made a steady stream of public appearances to tout his legislative priorities and harshly criticize many of President Donald Trump’s policies, including Tuesday’s announcement that he will wind down a program protecting young immigrants from deportation.

Menendez has also remained a leading voice against improved relations with Cuba and praised Trump’s rollback of President Barack Obama‘s plan to re-establish diplomatic relations.

The indictment also hasn’t stopped Menendez from receiving financial support. He has raised more than $6 million since his indictment, between his legal defense fund and campaign, according to a review of federal filings.

This article was written by David Porter of the AP.