New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has been accused of abusing his office by forcing a private Catholic charity to make billions of dollars worth of payments into an election-year “slush fund.”

Cuomo’s office strongly disagreed with that assertion–saying the fund was created to increase and sustain New York’s commitment to providing quality health care.

Originally noted by the Empire Center for Public Policy in a March 31 analysis by the fiscally conservative think tank’s director of health policy, Bill Hammond, the charge was reiterated in a Wall Street Journal op-ed late Monday. At issue is a controversial agreement between health insurance companies, Catholic bishops and the State of New York.

Fidelis Care is an indigent-focused health care provider founded in 1993 by the Diocese of Brooklyn. Since then, Fidelis has aggressively expanded and is now New York State’s top provider of health insurance to poor and low-income residents. In September, Centene Corp. agreed to purchase Fidelis for $3.75 billion–with the funds reportedly going to a charitable foundation administered by New York’s Catholic bishops.

That’s when the governor’s office stepped into the picture.

Cuomo is accused of moving to extract rent from the proposed sale between Fidelis Care and Centene. New York’s governor argued that because Fidelis earned most of its revenue from state-based-or-administered programs–like Medicare, Medicaid and Obamacare plans–the State of New York was entitled to $3 billon worth of the proceeds–an effective tax rate of eighty percent. Hammond noted, in his Monday op-ed, “[Fidelis Care] has played a big role in reducing the state’s uninsured rate, and it has not been publicly accused of wrongdoing. Despite lacking a legal claim to the money, Mr. Cuomo pursued it aggressively.”

An official in the governor’s office pushed back against this categorization, saying the issue could be boiled down to Fidelis having existed as a non-profit for years. When Fidelis moved to sale their assets to a private company, the state–on behalf of the public–was all but forced to act: otherwise, that official said, private parties could spin up non-profits all the time just to take advantage of their non-profit status.

Cuomo first made his request for most of those sale proceeds in a January budget proposal. In that proposal, Hammond says, “[Cuomo] cited the precedent of Empire Blue Cross Blue Shield, which converted from non-profit to for-profit status in the mid-2000s with 95 percent of the proceeds going to the state treasury. But that transaction required a change in the state’s insurance law that was tailor-made to one transaction. As an HMO incorporated under the public health law, Fidelis did not technically need the Legislature’s approval for its deal.”

While legislative approval was not necessary for the Fidelis sale, two state regulators–appointed by Cuomo– would have had to sign off on the deal. According to Hammond, Cuomo’s administration threatened to withhold those approvals until a satisfactory agreement could be reached with the State of New York. A source in the governor’s office could neither confirm nor deny this detail.

At the same time, Cuomo submitted two budget proposals seen as targeting Fidelis Care. The first was a reiteration of the January proposal–grabbing 80 percent of the sale proceeds. The second would have given New York State the authority to “require certain non-profit Medicaid managed care plans to disgorge reserve funds in excess of 150 percent of the mandatory minimum,” according to an earlier article by Hammond.

Ultimately, a compromise was reached. Hammond notes the contours of the deal in his WSJ op-ed:

In the face of a three-way bind…Fidelis and Centene agreed to give up $2 billion over four years, including $1.35 billion this year. The bishops’ charitable foundation is left with $3.2 billion, including both sale proceeds and surplus cash, and Centene salvages an expansion that has been well-received on Wall Street. But the state’s end of the deal creates the ugly appearance that regulatory approval of the Fidelis-Centene sale has been bartered for a 10-figure sum.

The Departments of Health and Financial Services still have to sign off on the deal, but the governor’s office does not expect any resistance on their end. So, that’s where things stand and how they got to this point. But what about the “slush fund” accusations?

A press release from Cuomo’s office referred to the deal as a “Health Care Shortfall Fund” which the release describes as “a fund to ensure the continued availability and expansion of funding for quality health services to New York State residents and to mitigate risks associated with the loss of Federal funds.”

As Hammond’s original analysis notes, however, the budget itself doesn’t contain the same language or limitations. In the legislation, the fund is referred to as a “Health Care Transformation Fund” which will be used “to support health care delivery, including for capital investment, debt retirement or restructuring, housing and other social determinants of health, or transitional operating support to health care providers.”

To be sure: these are little more than differing doses of PR speak and legalese. But Hammond also points to one interesting component of the deal and newly-created fund. The budget/revenue bill provides, in PART FFF SUBPART A, “moneys of the health care transformation fund shall be available for transfer to any other fund of the state as authorized and directed by the director of the budget.”

In plain language, this means that Cuomo’s office legally has the ability to re-allocate those funds anywhere the governor chooses. The bill also provides that, should such a reallocation of health care funds occur, the governor’s office has 15 days before they’re required to alert the legislature.

Morris Peters, with the New York State Division of the Budget provided the following statement to Law&Crime:

The asset being transferred was built on state payments and tax exemptions and, consistent with past precedent, state taxpayers should also benefit from privatization. Governor Cuomo brought the parties together to strike an amenable solution that will support the more than 6 million adults and children served by public health insurance and other affordable health care services, while also benefitting the Catholic Health Foundation and protecting State taxpayers.”

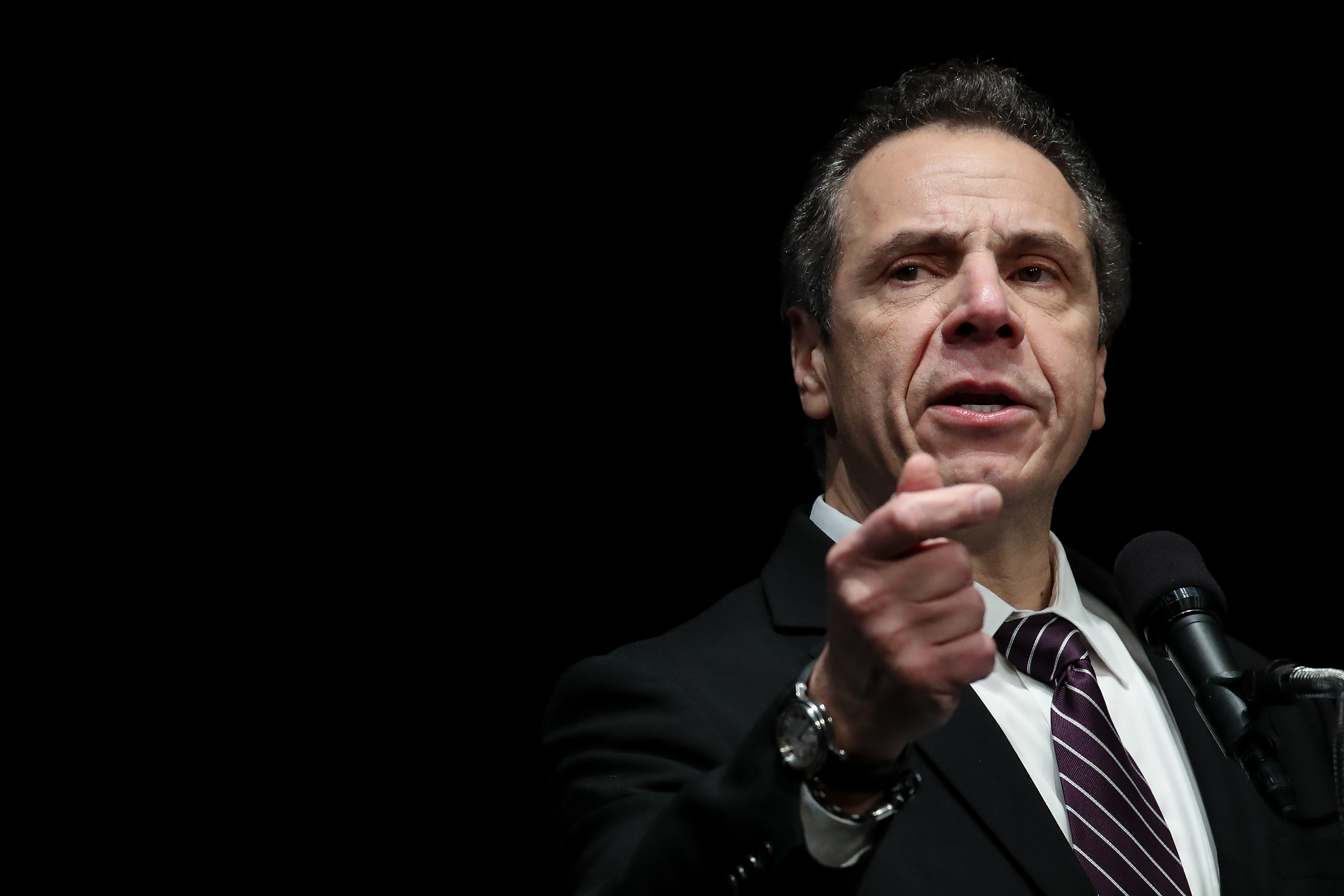

[image via Drew Angerer/Getty Images]

Follow Colin Kalmbacher on Twitter: @colinkalmbacher