The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) under President Joe Biden is going to the mat for former secretary of education Betsy DeVos.

In a Monday filing with the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida, Acting Assistant Attorney General Brian Boynton and other DOJ attorneys argued that students who were ripped off by for-profit scam colleges cannot depose the former Trump-era official.

“The [students’] demand for a former cabinet official’s deposition is extraordinary, unnecessary, and unsupported,” the filing alleges. “It is a transparent attempt at harassment—part of a PR campaign that has been central to [the students’] litigation strategy from the outset. It should be rejected and the court should quash the subpoena.”

Making common cause with the DOJ in the motion to quash is another Trump-era official: former acting associate attorney general Jesse Panuccio. Now an attorney with elite law firm Boies Schiller Flexner LLP, Panuccio is acting as DeVos’s personal attorney “and is represented in her capacity as former U.S. Secretary of Education by the U.S. Department of Justice,” the filing explains in a footnote.

As a matter of law, the Biden administration does not have to take on DeVos’s representation here. The DOJ picks and chooses whether to represent present and former officials—but they are not bound by any rules, regulations or federal statues to do so. Additionally, there does not appear to be any extant legal authority for the DOJ to represent DeVos here in her personal capacity because she’s not actually a party to the underlying litigation. In order for DOJ to represent DeVos like this, the agency is supposed to initially file a statement of interest but no such document has been filed in the case.

The underlying case concerns hundreds of students who were defrauded by various for-profit colleges across the country. The students, all federal student loan borrowers who are currently in debt, sued the U.S. Department of Education because DeVos’s agency was accused of serially dragging its feet when asked to process student loan debt cancellation requests.

Multiple courts in the Northern District of California agreed with the students. DeVos herself ultimately admitted that student borrowers had paid for educational programs that were effectively “worthless.”

Still, DeVos continued to collect student loan payments from some 75,000 defrauded students who attended classes at the Corinthian Colleges chain. In May 2018, U.S. Magistrate Judge for the Northern District of California Sallie Kim barred the Department of Education from collecting payments on those student loans in the case stylized as Martin Manriquez v. Elisabeth DeVos.

After that, DeVos and the Department of Education continued to try and collect on thousands of those loans—eventually being found in violation of a court order. The Department of Education later admitted to “erroneously” violating that court order.

After being forced to reconsider student debt cancellation requests, DeVos’s agency took their time—ignoring new requests for some 18 months. A different group of students sued, alleging DeVos’s “delay to be unlawful stonewalling.” Judge Kim certified those students as a class in Oct. 2019.

Now those students want DeVos to sit for a deposition. That request was recently signed off on by U.S. District Judge William Alsup.

As Republic Report journalist David Halperin noted in that outlet’s original reporting, DeVos was subpoenaed on Jan. 26—some 19 days after she resigned. But the motion to quash offers a notable timeline: DeVos formally tendered her resignation the day after she was alerted that the students were intent on having her deposed. DeVos submitted her resignation on Jan. 7—the day after the Capitol siege. She blamed Trump’s “rhetoric” for the impacting the mob and the “situation.”

But the Biden administration and DeVos’s private counsel have other plans. In their motion, Boynton and Panuccio criticize the district court for its orders and accuse the students and their attorneys of being little more than media hounds intent on harassment.

“Plaintiffs appear to be more interested in the deposition itself (and the press attention that might come with it) than in the information they claim to seek,” the DOJ motion alleges.

The Biden administration DOJ repeatedly takes issue with a press release issued by the students’ lawyers after Judge Alsup okayed the DeVos deposition.

“Plaintiffs rebuffed Defendants’ offers to explore alternative sources, and instead hastily rushed to the district court in the underlying action (overlooking the need for a Rule 45 subpoena) to try to secure their sought-after deposition while also filing a celebratory press release,” the motion notes at one point.

The DOJ criticizes the press release again in a section complaining that the students declined to wait for the conclusion of an internal Department of Education investigation before filing: “Plaintiffs waited less than five hours before filing their request for the former Secretary’s deposition—followed by a celebratory press release.”

A lengthy footnote critiques the press release further:

In that press release, class counsel frankly reveal that they view a deposition of the former Secretary as necessary because she allegedly has a generalized “obligation to explain why defrauded student borrowers were ignored for years by the Education Department and then summarily denied their rights.” But the APA creates no such legal obligation, an dthe press release’s statement stands in stark contrast to Plaintiffs’ claim to the district court that they merely seek narrow categories of information that is unavailable from other sources. And, of course, the press release shows that Plaintiffs’ counsel is seeking, through this high-profile deposition, to get much more than the only thing sought in the Complaint: a “simple” order compelling the Department [of Education] to “start granting or denying their borrower defenses.”

A source familiar with the litigation said the language used by the DOJ in the motion to quash was unusually harsh and striking. They questioned the decision to cast admittedly defrauded students as harassers trying to attain a PR coup—as well as the general decision by the Biden administration to defend DeVos in the first place.

Jeff Hauser, an attorney and the executive director of the Revolving Door Project—an offshoot of the left-wing Center for Economic and Policy Research think tank—told Law&Crime that the decision to defend former executive branch officials is not entirely unlike a norm that should have lapsed when DeVos quit her job.

“My understanding is that it is a (problematic) norm if she were still Secretary and not a norm now that she is not,” Hauser said. “And we also think that figures like Trump and DeVos long ago forfeited the benefit of such norms.”

Some have questioned whether the abrasive motion was written by DeVos’s counsel and then signed off on by government line attorneys and the acting attorney general after a cursory read-through.

The motion to quash the subpoena was jointly authored by Obama administration alum Boynton and Panuccio as well as DOJ attorneys Marcia Berman, R. Charlie Merritt and Kevin P. Hancock.

The subpoena itself notes that the deposition is ” to be conducted via remote technology, with witness located in Vero Beach, Florida,” which is how the government and DeVos managed to file their stonewalling effort in the notoriously anti-government transparency Southern District of Florida.

The students, for their part, are hoping to get the case back where they say it belongs—which also happens to be much-friendlier ground.

“We will seek transfer of DeVos’s motion to quash to the appropriate court in California where we will continue to press for her deposition,” Eileen Connor, the legal director for the Project on Predatory Student Lending at the Legal Services Center of Harvard Law School and one of the students’ attorneys, told Law&Crime.

Read the joint DeVos-DOJ motion below:

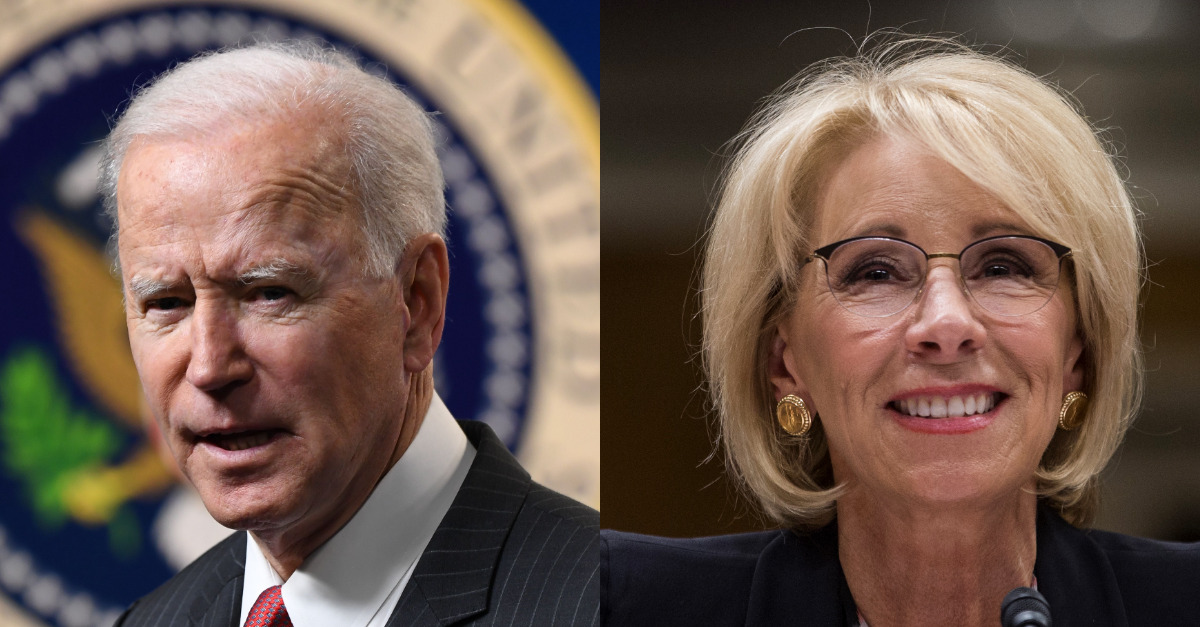

[image via SAUL LOEB/AFP via Getty Images; Zach Gibson/Getty Images]