Former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort is behind bars counting down the days to July 31, when his trial in the Eastern District of Virginia (EDVA) is scheduled to begin. Meanwhile, his attorney Kevin Downing is out there doing his best to convince Judge T.S. Ellis III that special counsel Robert Mueller and his team of prosecutors should not be allowed to use more than 50 pieces of evidence at trial.

Courthouse News’ Brandi Buchman had the story, but also has a thread going now about the evidence Downing says should be disallowed on grounds that it is irrelevant.

Downing said evidence relating to Manafort’s Ukraine lobbying work (mainly information about a past possible Foreign Agents Registration Act [FARA] violation that resulted in no charges against Manafort) should be tossed out because it has nothing to do with bank and tax fraud charges against Manafort and may prejudice jurors against his client.

“In reviewing the proposed exhibits, it is readily apparent that Special Counsel intends to offer evidence concerning matters that are irrelevant to this tax and bank fraud trial and therefore should be precluded,” Downing argued. “Moreover, even if the Special Counsel’s proposed exhibits were relevant, their admission should nevertheless be barred because their probative value is substantially outweighed by risks of unfair prejudice, issue confusion, delay and waste of time.”

Six days ago the government explained why it believed that the evidence was relevant and not prejudicial.

Why it’s relevant, according to Mueller:

By contrast, the evidence is relevant to proving Manafort’s knowledge of the (Foreign Agent Registration Act) FARA regulatory regime and the absence of any mistake when he failed to register with, and made false statements to, the FARA Unit as charged in the indictment. In particular, the government will prove Manafort’s knowledge of and familiarity with FARA’s requirements by establishing that previous interactions with the Department of Justice put him on notice of those requirements. Such usage [of this evidence] is proper. Admission of acts predating charged conduct to prove knowledge is expressly permitted under Rule 404(b) […] It is also commonly done in cases where a defendant’s prior interactions with a government regulator are used to prove the defendant’s knowledge. Such proof is of particular importance in this FARA prosecution: as this Court has observed, “FARA violations require evidence of willful conduct.”

Why it’s not prejudicial:

Rule 404(b), however, is not limited to evidence of prior criminal acts or even civil wrongs; by its terms, the Rule allows admission of “other act[s].” It therefore does not matter that [evidence about prior] FARA inspections did not result in criminal charges or other sanctions [against Manafort]. Indeed, the non-criminal nature of the prior acts underscores why the proffered evidence is not unfairly prejudicial under Rule 403. In arguing otherwise, Manafort contends that the evidence should be excluded under Rule 403 because it dates from the 1980s, that age reduces its probative value, and the risk of unfair prejudice (he claims) substantially outweighs that probative value. That contention lacks merit. While “the probative value of evidence c[an] be attenuated by the passage of time,” United States v. Rodriguez, 215 F.3d 110, 120 (1st Cir. 2000), “[t]here is no mechanical test for determining whether evidence of a prior offense is too remote to be admissible.”

Manafort’s attorneys provided a list of all of the evidence they don’t want Mueller to use. You can see that in the filing below.

Paul Manafort 7:26:18 by Law&Crime on Scribd

Manafort does face a charge in D.C. for an alleged violation of FARA related to his Ukraine dealings. Manafort has lost arguments time and again when arguing that the Mueller investigation is operating outside of its specified scope.

Manafort has argued, for instance, that it was improper for the government to charge him in the D.C. case under FARA because FARA deals with being an unregistered agent of a foreign principal. He asserted that the violation of FARA is willfully failing to register, not any act that he is otherwise accused of in connection with his work for the Ukrainian government.

Judge Amy Berman Jackson refuted this argument with a simple and direct quote from the statute: “[n]o person shall act as an agent of a foreign principal.” The word “act,” of course, meaning that it’s the action one undertakes as an agent that triggers the violation, provided the person did not register. In this case, the complaint against Manafort outlines alleged acts in violation of FARA, and alleged money laundering is claimed to be in promotion of that violation.

Manafort was correct to bring up “will,” however. This competent makes a difference for sentencing length.

Sandler Reiff Lamb Rosenstein & Birkenstock’s Joshua Ian Rosenstein previously explained to Law&Crime about FARA that the maximum penalty is $10,000 in fines and up to 5 years imprisonment for “willful” violations, calling “willful” a “less stringent standard than ‘corrupt.’”

Rosenstein said that even though FARA is “rarely enforced criminally, its criminal enforcement is still more frequent than the LDA (Lobbying Disclosure Act), which usually yields civil penalties and fines rather than criminal penalties.”

“FARA charges are often brought as adjuncts to larger criminal behavior, such as financial crimes, and usually involve higher-profile matters,” he said. “And those FARA charges are often used as bargaining chips for larger plea agreements (which is what happened with Mr. Gates, and with Gen. Flynn).”

Former federal prosecutor Renato Mariotti would add that for a FARA violation to be a crime, it would have had to be done “knowingly and willfully.”

Ronn Blitzer contributed to this report.

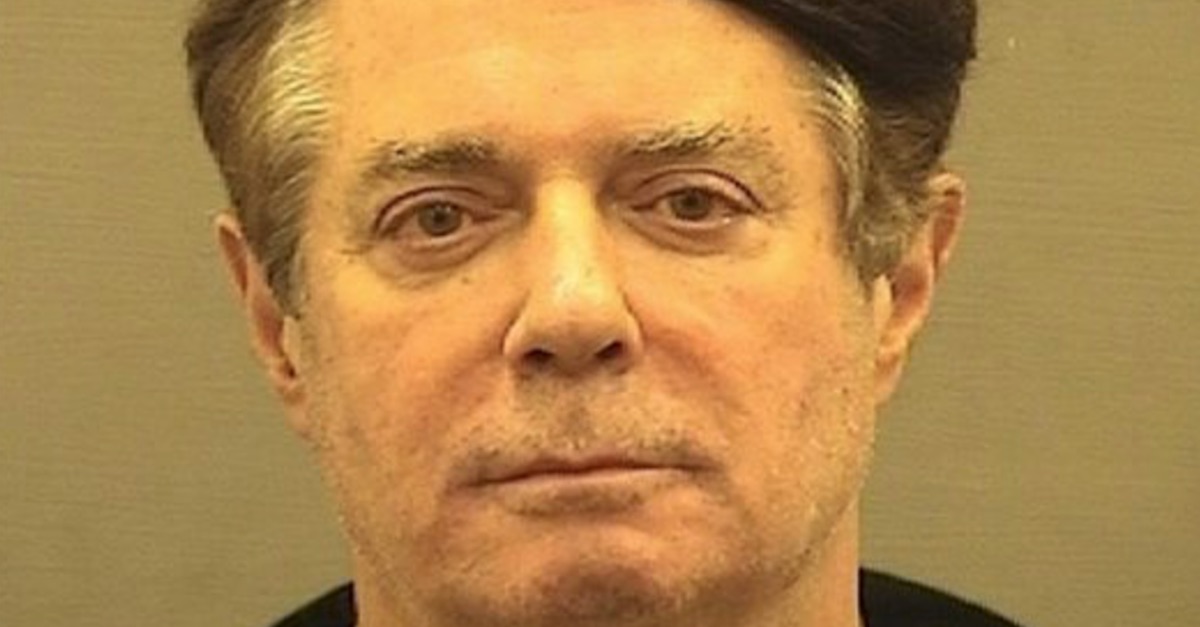

[Image via Alexandria Detention Center]