ABA Legal Fact Check debuted in August and is the first fact check website focusing exclusively on legal matters. This article has been republished with permission.

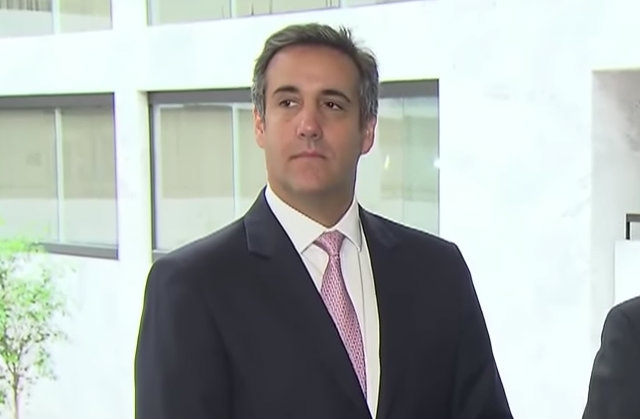

On April 9, the FBI raided the New York law office and temporary residence of lawyer Michael Cohen. The next day his most well-known client, President Donald Trump, tweeted: “Attorney-client privilege is dead!” Trump’s tweet raises the question of how far the privilege extends.

The confidentiality of communications between a client and his or her attorney is one of the oldest recognized privileges, dating back to at least Queen Elizabeth I in English common law. The U.S. Supreme Court first upheld the privilege in 1906. Since then, though, courts have ruled it is not absolute.

In a 1998 majority opinion in the investigation of President Bill Clinton, U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist summed up the importance of the attorney-client privilege. Borrowing from prior court decisions, he wrote that it is “intended to encourage ‘full and frank communication between attorneys and their clients and thereby promote broader public interests in the observance of law and the administration of justice.’”

The case involved three pages of notes generated by the lawyer for former White House aide Vincent W. Foster Jr. As part of his investigation into the Whitewater real estate deal, independent counsel Kenneth Starr sought the document through a grand jury. Foster was found dead nine days after the conversation occurred with his lawyer, presumably by suicide; the court ruled 6-3 that the attorney-client privilege survived past the death of a client.

But what makes a conversation or other exchange subject to the privilege? Mere communication with a lawyer – or in the presence of a lawyer – is not sufficient. If the communication was intended to be confidential to one’s lawyer, it likely would be privileged. But acts of a client, unrelated to communications with the attorney as legal advisor, generally are not.

The prevailing principle, articulated by a federal district court in Massachusetts in 1950, spells out certain parameters to argue for the privilege. In general, it applies only if (1) the asserted holder of the privilege is or sought to become a client; (2) the person to whom the communication was made is a member of the bar of a court, or a subordinate; (3) the encounter occurs when the lawyer is acting in a legal capacity and the exchange is not for the purpose of committing a crime and (4) the privilege has been claimed by the client.

Over time, courts have carved out three general exceptions to the attorney-client privilege, with the crime/fraud exception cited most. The other two involve a fiduciary exemption, which typically applies to trust and estate cases, and the “on the advice of counsel,” which would be used as a defense.

The crime-fraud exception was set by the U.S. Supreme Court in Alexander v. United States more than 100 years ago. The legal principle is now well defined, and covers communications between an attorney and client that further a crime, tort or fraud. In 1989, in United States v. Zolin, the court laid down additional guidelines on how lower courts should decide in camera review, or private inspection, to determine whether purportedly privileged attorney-client communications fall within the crime-fraud exception.

“Before a district court may engage in in camera review at the request of the party opposing the privilege, that party must present evidence sufficient to support a reasonable belief that in camera review may yield evidence that establishes the exception’s applicability,” the opinion written by Justice Harry Blackmun said.

Because the privilege belongs to the client, it is the client’s intent that determines whether the crime-fraud exception applies. That means the exception could apply even if the attorney was not a knowing participant in the underlying crime or fraud.

A search of the files of an attorney is considered among the most sensitive moves federal prosecutors can make as they pursue a criminal investigation, and U.S. Department of Justice guidelines (see 9-13.420 – Searches of Premises of Subject Attorneys) require the express approval of the U.S. attorney or pertinent assistant attorney general.

In the case of Cohen, who has been linked to payments to two women who claimed trysts with Trump before he became president, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein reportedly approved the request for a search warrant. The guidelines say that a warrant is justified when an attorney is a “suspect, subject or target” of an investigation or “is believed to be in possession of contraband or the fruits or instrumentalities of a crime.”

A federal magistrate or federal judge would still need to approve the request, and would do so only after determining that the privilege has been waived by falling within one of the three exceptions.

Read more of ABA’s Legal Fact Check series here.

[Screengrab via MSNBC]