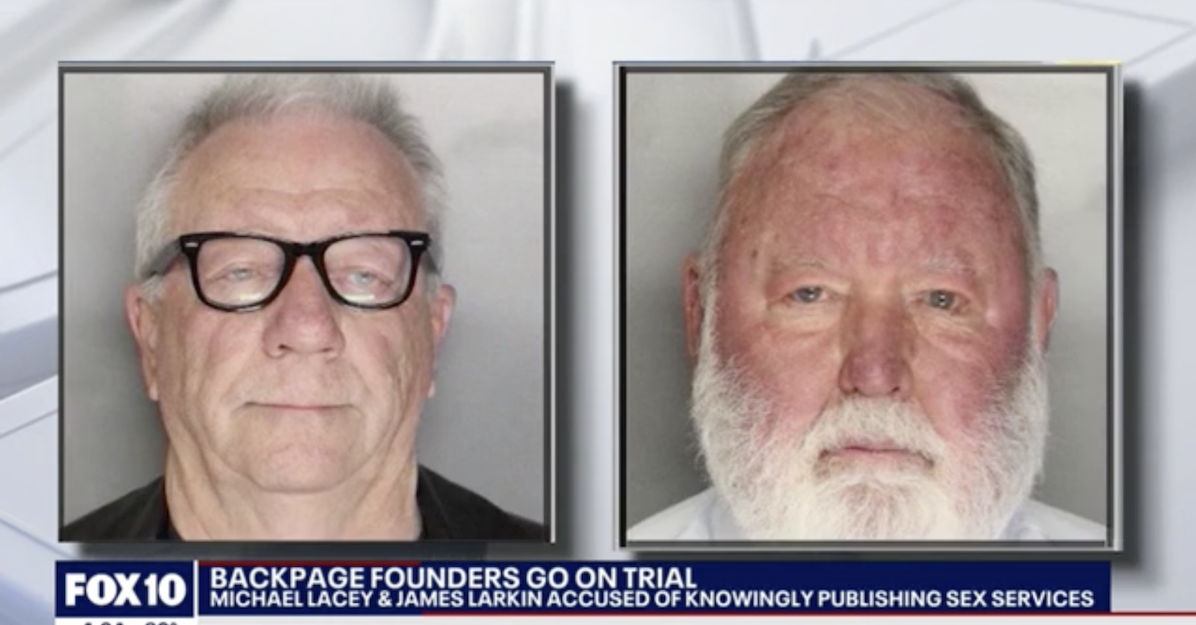

Backpage co-founders Michael Lacey (left) and James Larkin (right) appear in a KSAZ-TV screenshot.

Lawyers for the operators of the former Backpage sex advertisement website told an appellate panel on Friday that a mistrial in Arizona last year means the six can’t be retried on prostitution-related charges because prosecutors planted problems to purposely ruin the trial.

“The government knew it could not deliver the case it had promised to the jury,” Whitney Bernstein told a three-judge panel in San Francisco, so prosecutors secretly wanted a mistrial.

Not true, said Assistant U.S. Attorney Peter Kozinets.

“We do not agree that the government was trying to sabotage the case,” Kozinets told the judges.

The case before the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals employs the legal theory that prosecutors can’t retry a defendant if they previously goaded a mistrial.

Trial judges have broad discretion when deciding whether goading occurred, but lawyers for James Larkin and Michael Lacey pointed Friday to an unusual reason not to accept U.S. District Judge Diane Humetewa’s rejection of their dismissal motion in this case: She’d been on the case only a couple weeks after the judge who declared a mistrial recused herself, and she “had the unenviable task of parachuting into this complex, lengthy case 3 1/2 years in the prosecution mid-motion,” argued Bernstein, who is representing Larkin. Larkin and Lacey are co-defendants with fellow Backpage founders Scott Spear, John Brunst, Andrew Padilla and Joye Vaught.

Appellate rulings that have backed other judges who rejected goading arguments involved judges who presided over the cases much longer than Humetewa had in the Backpage case when she declined to dismiss it.

Bernstein mentioned this on Friday, referencing the 9th Circuit’s rejection of Michael Avenatti’s appeal in his California criminal case, which hinged on a similar argument that prosecutors had goaded the mistrial and thus double jeopardy applied. The court issued its order rejecting the appeal five days — including a weekend — after hearing argument, an extraordinarily fast turnaround.

But Bernstein differentiated the rejection of the dismissal motion in Larkin and Lacey’s case from Avenatti’s case by noting that Humetewa had little experience with the case.

The judge who recused herself after declaring a mistrial, U.S. District Judge Susan Brnovich, did not state a reason for doing so, but she’d previously been targeted for recusal because she is married to Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich, who has spoken out against human trafficking. In refusing to recuse herself before trial, Judge Brnovich differentiated the case from one against the business entity Backpage, it’s about whether individual executives knew the website had advertisements that facilitated prostitution.

The Sept. 14, 2021, mistrial stems from prosecutors focusing too much on child trafficking in their opening statement and in their questioning of witnesses, which Brnovich said “abused” the court’s leeway and unfairly tainted the jury. Brnovich granted a mistrial orally and never issued a written ruling. She then recused herself on Oct. 29 with no explanation.

Bernstein said federal prosecutors in the District of Arizona purposely interjected inflammatory material into their case because they knew it defense attorneys would ask for a mistrial because of it. She and other defense attorneys have long said the prosecution is barred by the First Amendment, and that the defendants at all times operated the website legally.

Senior Judge William Fletcher, a 1998 Clinton appointee, and Senior Judge Jay Bybee, a 2003 Bush appointee, are deciding the case with Judge Lawrence VanDyke, a 2019 Trump appointee.

Their comments Friday don’t bode well for Larkin and Lacey’s attempts to rid themselves of the case, filed in 2018 as part of a federal crackdown on Backpage that also targeted the website itself and its CEO, Carl Ferrer, who testified in trial for the prosecution. Authorities say Backpage generated $500 million in revenue when it was shuttered in April 2018; Lacey and Larkin owned it as part of an investment portfolio that at one point included the founded the Phoenix New Times newspapers and ownership interests in other weeklies such as The Village Voice.

Fletcher said he wasn’t sure prosecutors’ conduct demonstrates an intention to force a mistrial.

“We’ve seen a lot of misbehavior over the years,” Fletcher said. “But the government’s behavior to me does not seem egregious.”

He said the “line” established by Brnovich was “pretty vague.”

Bybee agreed.

“The orders really weren’t very clear. I think this was a difficult line to police,” Bybee said.

Lacey’s lawyer, Paul Cambria, of Lipsitz Green Scime Cambria LLP in New York City, said prosecutors had no trouble understanding the guidelines, as evidenced by their own words in trial: “We understand your instruction and we’ll tell our witnesses.”

Fletcher noted the prosecution’s “strenuous” opposition to the mistrial request, though Bernstein, a partner at Bienert Katzman Littrell Williams LLP in San Clemente, California, said while they objected to previous mistrial requests, they didn’t try to dissuade Brnovich when she finally declared one.

But Kozinets said prosecutors worked hard to stay away from questions about child trafficking and other seemingly inflammatory areas after being warned by the judge, out of a strenuous desire to avoid a mistrial.

“There’s no question that the government didn’t want a mistrial,” Kozinets said.

Watch the 9th Circuit argument below.