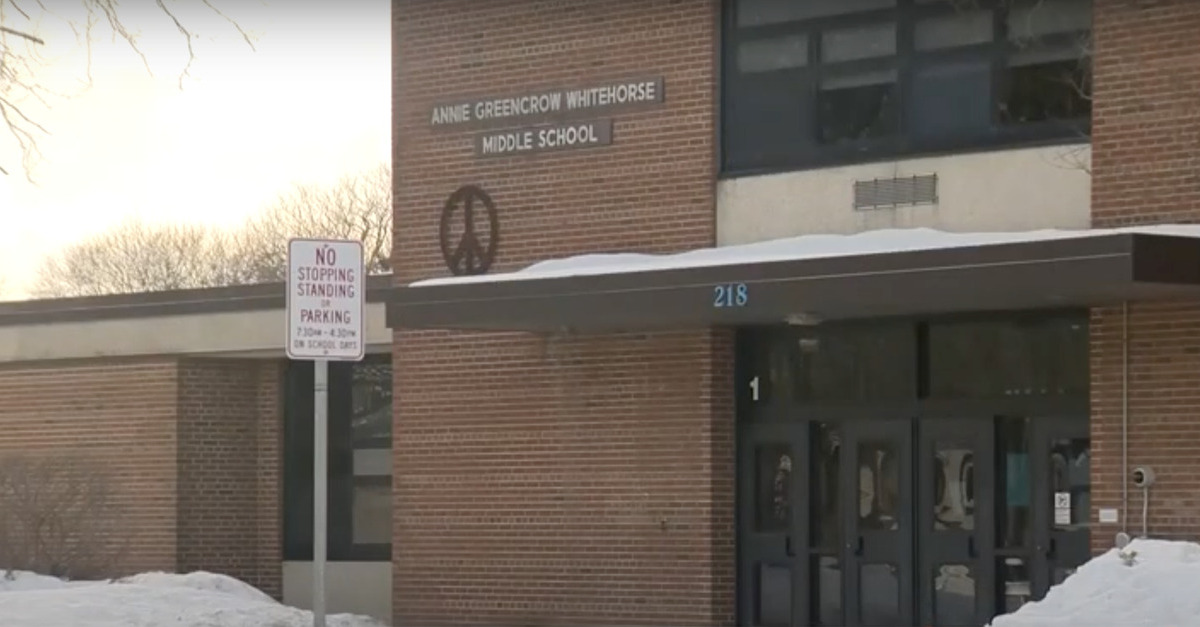

Anne Greencrow Whitehorse Middle School in Madison, Wisconsin

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit sided with a Wisconsin school district Tuesday, and affirmed a summary judgment ruling against a middle schooler who claimed her principal failed to protect her from a predatory security guard.

The case was filed on behalf of a middle schooler known in court documents as “C.S.” The disturbing allegations are that while C.S. was an eighth grader at Whitehorse Middle School in Madison, Wisconsin, a school security assistant named Willie Collins repeatedly sexually abused her. The abuse is alleged to have included Collins making sexual comments to C.S., kissing her, fondling her breasts, and digitally penetrating her. C.S. did not report the alleged abuse at the time it happened, and there is no evidence that anyone witnessed it.

Once C.S. left middle school to attend high school, she reported the alleged abuse. The district responded by placing Collins on administrative leave and conducting a criminal investigation. However, C.S.’s Title IX lawsuit against the district claims that although the school officials were unaware of the specific allegations of sexual abuse C.S. endured in the eighth grade, they had been on notice of Collins’ alleged inappropriate behavior in the year prior.

During C.S.’s seventh-grade year, Collins regularly interfaced with students as both security guard and mentor. U.S. Circuit Judge Michael Scudder (a Donald Trump appointee) wrote for the 7th Circuit and detailed the allegations against Collins:

He regularly gave students—boys and girls alike—hugs, often apparently initiated by the students themselves. Tracy Warnecke, the school’s positive behavior support coach, testified that she saw Collins giving back or shoulder rubs to students—again, boys and girls alike—at lunch time “three to four times a week.” But Warnecke also observed troubling interactions between Collins and C.S. She frequently saw C.S. asking Collins for hugs and spending time “in his office after school,” and on one occasion saw C.S. attempt to kiss him on the cheek, though he rebuffed her efforts. According to Warnecke, C.S. then tried to kiss him again, but “he stopped it and then took her for a private conversation because we were in the hallway.”

Those incidents were reported to the school principal both by Warnecke and several other teachers who witnessed the alleged behavior. Principal Deborah Ptak, in response, told Collins to “limit” the “hugs and physical contact” with C.S. and to “set strong boundaries” with her, the court’s opinion indicates.

In the time that would follow, the principal found no further reason for concern and received no further reports of misconduct, the court’s opinion goes on to state. According to C.S., however, that was because the abuse was thereafter perpetrated in private.

The district court granted summary judgment in favor of the school district, and a three-judge panel of the 7th Circuit affirmed that decision. The plaintiff appealed and the full 7th Circuit — including now-Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett — heard oral argument for the case’s rehearing. Justice Barrett took no part in the ruling now that she has ascended to the nation’s highest bench.

Writing for the full 7th Circuit, Scudder asserted that the court’s opinion should be used to clarify Title IX’s application in cases involving the kind of misconduct alleged by C.S. He explained that liability under Title IX is rooted in contract — not tort — principles. Accordingly, “liability may attach only where a court can be sure ‘that the grantee was aware that it was administering the program in violation of the [condition].'” As a result, the fate of C.S.’s case against the school district comes down not to whether Collins committed bad acts, but whether the district had “actual knowledge and deliberate indifference” to those acts.

Turning to the facts at hand, Scudder was clear to underscore that C.S.’s own behavior (specifically, reports that C.S. had exhibited an “infatuation” with Collins and had initiated some physical contact with him) was irrelevant to the application of Title IX.

“The controlling question is only whether the conduct Principal Ptak knew about — regardless of who initiated it — amounted to discrimination on the basis of sex giving rise to an obligation to take further action,” Scudder wrote.

The full 7th Circuit was satisfied that Ptak had done enough to satisfy the school’s legal obligation.

“Principal Ptak—to her credit—clearly saw the situation as requiring immediate action,” Scudder wrote, praising the principal. “That common-sense foresight led her to confront Collins in April 2013.”

Scudder pointed to the trial court’s findings that Ptak’s response was not so unreasonable as to constitute “deliberate indifference” and that Ptak reasonably believed that her conversation with Collins sufficiently remedied the situation.

Scudder’s 21-page opinion concluded with an acknowledgment that applying case law to Title IX questions involving allegations of sexual abuse “is hard and messy, no doubt reflective of the immense challenges school administrators face when confronted with the alleged sexual abuse of a student.”

Attorneys for the parties did not immediately respond to request for comment.

Read the decision from the 7th Circuit below.

[screengrab via WISC]