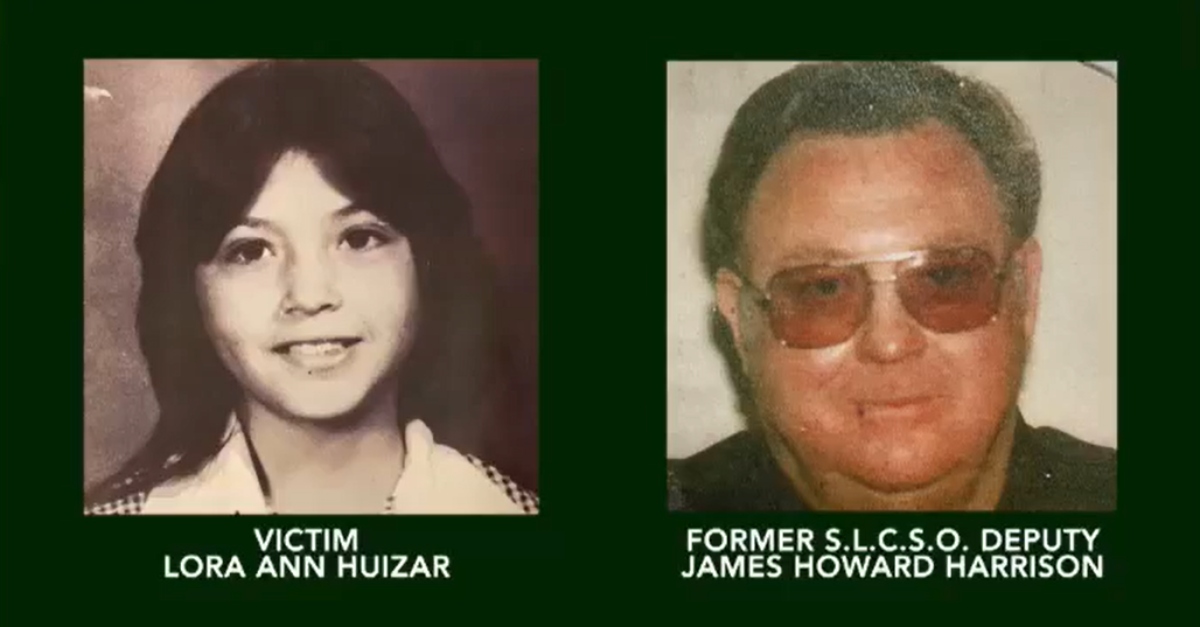

Lora Ann Huizar and former deputy James Howard Harrison.

Investigators say they found some closure in the case of a slain girl, but their answer to the longtime mystery was all too close to home. Former St. Lucie County Deputy James Howard Harrison, who is dead, is the “only probable suspect” in the rape and killing of Lora Ann Huizar, 11, in 1983, the sheriff’s office announced on Thursday.

Harrison is the person who put Huizar’s body in a drainage ditch near where she went missing, and he even told two witnesses who found the body to leave before other law enforcement arrived, officials said. The sheriff’s office describes Harrison as having a checkered history, even facing contemporaneous molestation allegations from his work as a preacher. They worry there may be more victims, in particular juvenile girls.

Huizar disappeared on Sunday, Nov. 6, 1983 after spending the night at a friend’s home, authorities said. Her father reported her missing, but back then, it did not set off alarm bells for authorities. According to Detective Paul Taylor, investigators in that period always assumed if a juvenile was missing they were spending time with friends, hanging out, or doing something else. He quoted one of the investigators: “‘That’s how that case was.'”

The situation changed for the worst when witnesses found Huizar’s body in a drainage ditch approximately 600 yards to the southeast of where she was last seen.

Taylor said that when he picked up the case two years ago, Harrison was not a suspect. That evolved as he went back, speaking to the witnesses as well as the original investigators. His investigation led him to Harrison, a long-time law enforcement officer with a checkered past.

It was Harrison, a uniformed patrol deputy, who saw Huizar walking home from a gas station on Nov. 6, 1983, according to Chief Deputy Brian Hester, who cited an original law enforcement report. This was within view of her driveway, Taylor said. The detective said that even back then, however, a law enforcement officer who saw Huizar carrying a bundle of clothes would have assumed she was a runaway and would have just stopped to at least talk to her. He wondered why a deputy would not have driven her home.

Authorities now say that Harrison told witnesses to leave the scene where Huizar’s body was found — approximately 20 minutes before other law enforcement arrived.

Both the location Huizar disappeared from and the location where she was found dead were within the deputy’s patrol zone, authorities said.

The original investigators never went back to speak to the witnesses, Taylor said Thursday.

“There was a lot of things missed in that investigation,” he said.

The sheriff’s office is emphatic that they have probable cause against Harrison, though they say they cannot seek charges against him because he died in 2008. Taylor said it was his understanding that Harrison died from cancer.

He voiced having complicated feelings about telling Huizar’s family that authorities solved the case.

“That day was my best day in law enforcement, and it was also my worst day,” he said. “It’s still my worst day because I am actually standing there in front of this victim’s family and I’m telling them that one of our deputies is the one that did it.”

From what investigators described, DNA evidence was the main sticking point in confirming Harrison as the killer. DNA from the sexual assault kit showed the suspect was male, but it was degraded too much by the time they were able to exhume Harrison’s body and compare samples.

Even so, officials highlighted the deputy’s suspicious history. He resigned in 1984, five months after the homicide, after revealing that he faced molestation allegations as part of his work with Bethel Baptist Church in the city of Fort Pierce. Harrison showed up with his wife at the now-retired chief deputy’s home to reveal the claims, Taylor said.

“The chief said, ‘Get off my porch,'” the detective said. The chief deputy called then-Sheriff Lanny Norville to get rid of Harrison.

Current Sheriff Ken J. Mascara revealed he used to work with Harrison, and he said he voiced concerns about the deputy’s interactions with young people. He said, however, that his complaints did not go anywhere at the time he made them, around 1979 or 1980.

“He was actually a zone partner of mine when I was on the road, and I want to guess it was around ’79 or ’80, I had made a complaint to my supervisors that I thought this deputy was having inappropriate relationships with young adults,” Mascara told reporters on Thursday. “Not sexual. Not anything like that, but his interactions with young adults I thought were inappropriate.”

But in this story, a supervisor said that under his work as a preacher, Harrison was mentoring at-risk children and teenagers. In retrospect, Mascara voiced concern that Harrison could have been using his job as a deputy and work as a preacher to “violate” children.

For example, Taylor noted that many migrant workers made their way through the state back then, and he suggested that Harrison might have gone after their children.

Taylor said that other agencies knew Harrison as “Preacher.” In his lengthy career, the now-deceased Florida law enforcement officer worked with 10 agencies: the Orange County Sheriff’s Office, Brooksville Police Department, Groveland Police Department, Hernando County Sheriff’s Office, Osceola County Sheriff’s Office, Edgewood Police Department, St. Lucie County Sheriff’s Office, Glades County Sheriff’s Office, the Okeechobee County Sheriff’s Office, and the Okeechobee Police Department, the detective said.

Asked how Harrison could keep working in spite of his history, Taylor said that the way they hired and fired people back then was based on the resume. Citing the old assistant chief, he said these men would get into a job and it wasn’t like you could get on the Internet and do a background check, or get a master phone log.

Hester asked Floridians for any information about Harrison or his involvement in another criminal investigation to contact the St. Lucie County Sheriff’s Office Criminal Investigations Division at (772) 462-3230.

[Images via St. Lucie County Sheriff’s Office]