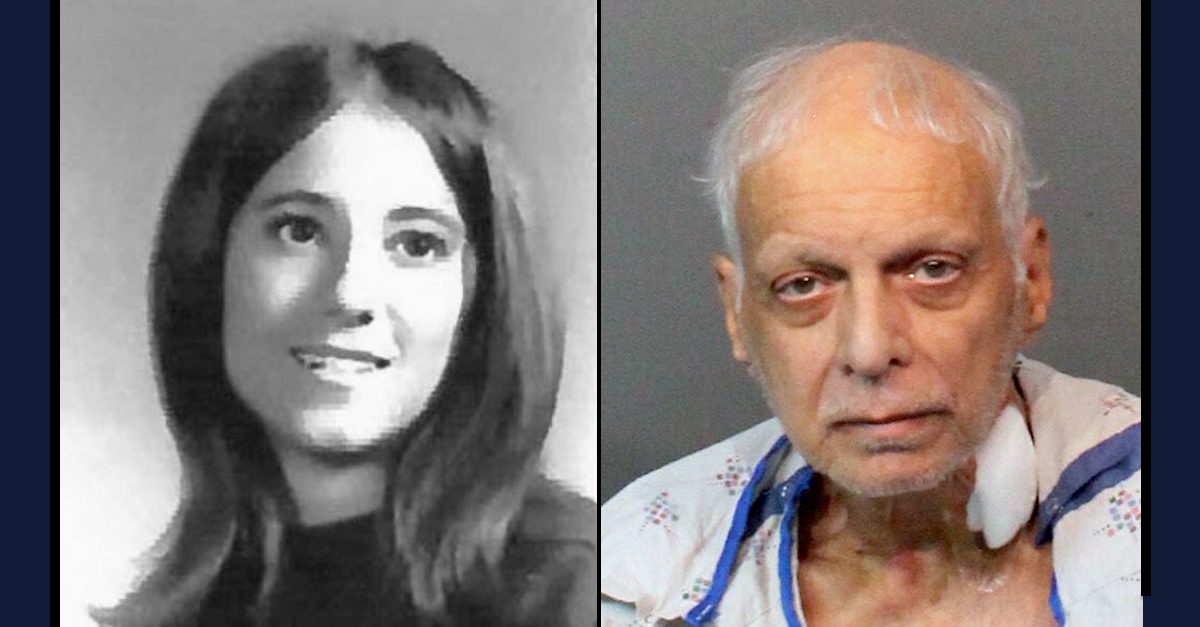

Murder victim Nancy Anderson appears in a photo released by the Honolulu, Hawaii police department; Tudor Chirila Jr. appears in a mugshot released by the Reno, Nevada Police Department.

New details have emerged in a Hawaii cold case murder dating back more than 50 years — including the subsequent and surprising work history of the man charged in connection with the slaying.

Tudor Chirila, also known as Tudor Chirila Jr., now 77, was taken into custody in the Reno, Nevada area on Tuesday. As Law&Crime previously reported, Chirila is charged with murdering Nancy Elaine Anderson in the late afternoon hours of Jan. 7, 1972, in the victim’s Hawaii apartment. Anderson had moved to Hawaii from Michigan just a few months prior — in October 1971 — and was working at a local McDonald’s. She was 19 when she died.

According to court documents, initial fears by neighbors that Anderson had killed herself in her bathroom were swiftly rubbished when police initially examined Anderson’s injuries: stab wounds to the neck, chest, stomach, back, sides, and both arms were apparent. Wounds to Anderson’s legs and a possible defensive wound on Anderson’s thumb suggested that murder, not suicide, was afoot.

An autopsy added to that belief: 63 separate wounds were visible, including three which police described as exit wounds from a blade. The cause of death was “[h]emorrhage due to stab wound of heart.”

There was no evidence of rape, and tests did not reveal the presence of drugs.

A modern photo shows Nancy Elaine Anderson’s apartment building. (Image via a Honolulu Police Department press release.)

A tip reportedly led the police to Chirila; his son, listed as John Chirila of Newport Beach, California, provided a DNA sample which suggested a link with DNA recovered from a towel found at the crime scene. John Chirila’s DNA did not match samples from the towel, court records indicate, but an analysis indicated he was likely the biological son of the person whose DNA was on the towel.

From there, law enforcement officers secured a warrant for Tudor Chirila’s DNA; a sample was subsequently secured by police in Reno, Nevada. A match was allegedly discovered with one of several samples taken from a towel found near an interior door at the crime scene, and Tudor Chirila’s DNA also could not be excluded as a match to two other samples from the same towel. Additionally, the father’s DNA could not be excluded from another towel found in a fire escape stairwell at the victim’s apartment building.

An arrest warrant soon followed, and Chirila was taken into custody in Nevada. Court paperwork filed in Hawaii and obtained by Law&Crime says the defendant attempted to take his own life shortly after the DNA sample was taken.

Citing police reports surrounding a reported break-in of the defendant Chirila’s car in March 1971, court documents say Chirila once worked as a Graduate Assistant at the University of Hawaii; he maintained a Kinau Street address in Honolulu.

After leaving Hawaii, Chirila reportedly went to law school, graduated, and worked as a Deputy Attorney General in Nevada, according to the Associated Press. The New York Post described Chirila as a “longtime attorney in Reno, Carson City and the Lake Tahoe area” who eventually ran for election to the Nevada Supreme Court in 1994. Chirila lost that election.

A 1980 Nevada Supreme Court case reviewed by Law&Crime lists Chirila as the Silver State’s Chief Deputy Attorney General serving under Attorney General Richard H. Bryan. A subsequent 1981 case, however, lists Chirila only as a deputy attorney general. A 1986 case and a 1987 case both list him as a senior assistant to the Reno City Attorney. The cases reviewed by Law&Crime which list Chirila as a litigant are civil, not criminal; most involved taxation issues or estate planning matters. The latter appears to have been an appellate focus once Chirila entered private practice.

The Post said Chirila was also named in a 1998 by federal indictment against A.G.E. Corp., a company that “served as a front for Nevada brothel boss Joe Conforte.”

A Nevada bar listing reviewed on Friday by Law&Crime indicates that Chirila resigned as of the state’s legal community, but no date for that resignation is given. He entered practice in the Silver State on Sept. 25, 1978, under bar number 884; his law school is listed as Sacramento, California’s Pacific McGeorge School of Law.

This sketch of what Nancy Elaine Anderson’s killer may have looked like was produced by Parabon NanoLabs and released by the Honolulu Police Department several years ago. The rendition is based on genetic information contained in DNA recovered from the crime scene.

The road that led the authorities to Chirila was long, winding, and arduous.

Interviews, lie detector tests, and even DNA tests over the decades involving many of the victim’s friends, co-workers, associates, and roommate in Hawaii turned up little of value, court documents indicate. More specifically, those efforts failed to yield a viable suspect.

Door-to-door salesmen who attempted to sell cutlery to the victim and her roommate several hours before the murder also did not turn out to be viable suspects, the paperwork reveals. The salesmen’s fingerprints didn’t match any at the crime scene, and they both passed polygraph tests. Additionally, the salesmen told the police that they started their sales presentation at around 1:30 to 1:45 p.m. on the day of the killing; the victim’s roommate joined the pitch session at about 2:30. They said they left shortly thereafter. Apparently the victim did as well: records at a nearby Bank of Hawaii location show that Anderson opened an account in person sometime after the sales pitch concluded. The teller who handled the transaction estimated that Anderson was at the bank somewhere between 2:15 and 3:00, but likely at the latter end of that time bracket, since the teller returned from break at 2:15. Anderson’s was the second the teller said she returned from her break.

Based on the time it would take for Anderson to walk home from the bank, the police estimated that the killing probably happened somewhere between 3:10 p.m. and 5:15 p.m.

Anderson’s roommate awoke around that time, found the victim body in the bathroom, and called the police; the first units responded at 5:29 p.m., police documents indicate.

The roommate, Jody Spooner, described Anderson as “too friendly with strangers” and as a person who “would talk to anyone on the street without regard to her personal safety,” according to a police affidavit.

The roommate’s boyfriend, Kim Weaver, said Anderson associated with men he knew only by nickname: “Reno Nevada,” “Cowboy,” “Frenchman,” and the “Dude from Detroit.”

The man known as “Reno Nevada” was identified as William Menor, not the suspect eventually charged with Anderson’s murder. According to court paperwork, Menor said he dated Anderson but hadn’t been to her apartment, hadn’t been sexually active with her, and didn’t know her phone number. He said he met Anderson and made plans with her through apparently frequent yet “chance meetings at the beach.” Menor also claimed to have also seen Anderson hanging out with other men, but he did not know their names.

“Menor described Anderson as a very nice girl with a great personality but felt she could have been a little less friendly with strangers,” the court papers indicate.

It is unclear from the available police affidavit whether Menor had any connection to Chirila, who worked for years in Nevada and was arrested in Reno.

A friend to Weaver and Spooner, Richard Hacker, told the police that Anderson “would bring home ‘weird looking guys’ and dated several different men,” but he did not know their names, the police wrote.

Anderson moved to Hawaii from Michigan shortly after graduating from high school in the Great Lakes State. Two co-workers said Anderson claimed to have dated a man “back home” who was “a member of the Mafia,” the police noted, but the connection was never fully explained in the available affidavit.

The statements of one of Anderson’s co-workers, Julie Torres, were summarized in police documents accordingly: “[s]he [Torres] did not believe Anderson was promiscuous but did feel that she was too friendly.”

Neighbors allegedly told the police that they observed “fellas going in and out” of the vicitm’s apartment at times.

One of Anderson’s managers described her to the police as “dependable and friendly employee.”

Court documents indicate that Anderson revealed to a friend that a second, separate manager may have attempted to ask her out and even propositioned her for sex. A polygraph registered “reactions” when that manager was asked about his amorous thoughts toward Anderson but registered “no reaction” when he was asked about the murder. Additionally, that manager’s fingerprints did not match any at the crime scene.

The Hawaii court documents cited in this report are embedded below: