A crackpot conspiracy theory managed to gain traction on social media on Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, through the ensuing weekend, and into Monday. It fermented on Twitter and Parler with a putrescence generally emitted only by liquefied farm runoff on a hot summer day, yet by all accurate calendars, it was, indeed, the comparatively unscented month of December.

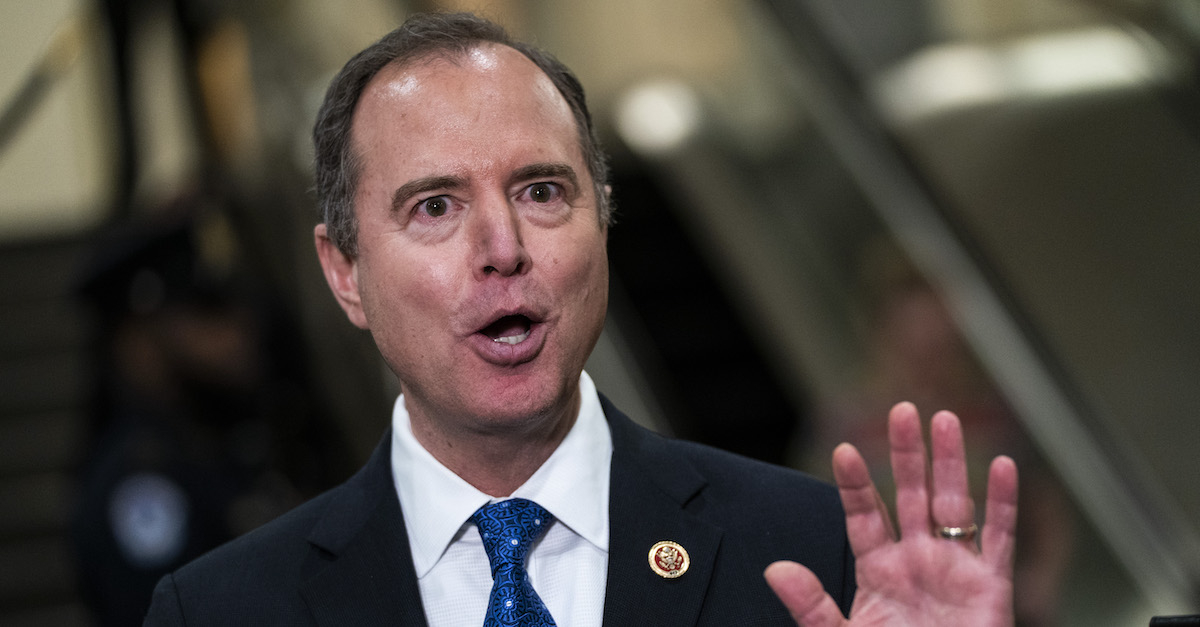

The erroneous online claims purported to assert, in various forms, that Rep. Adam Schiff, the California Democrat who was the lead prosecutor during President Donald Trump’s impeachment, had been either arrested or questioned at LAX by either the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, the Los Angeles Police Department, or by the FBI—or perhaps by some combination of those agencies. It even wrongly suggested that third-party, unofficial “sources” of arrest information contained proof of the arrest (they didn’t) and that the media was hiding critical information (it wasn’t). The suggestions were amplified by pro-Trump attorney Lin Wood, who suggested in his own words that Schiff was “not having a good Christmas.” It is unclear what Wood actually meant, but several people apparently interpreted his words to mean that there was something to the rumors about Schiff.

The rumors weren’t true, and they still aren’t true. Multiple official sources corroborate that Schiff wasn’t arrested.

Attacks on the media were part of this inaccurate and at times derogatory exercise. Predictably, some of the accounts (see: @MelaniasRhonda) which spread the false claims have since been suspended by Twitter, and others talked down the claims or backed down on the original hype. Law&Crime captured screenshots, however, of what all too many gleeful shared and liked as many Americans concomitantly celebrated Christmas.

Arrest Records Are Generally Considered Public Records

Arrests are acts undertaken by the government, and they are serious acts: they directly interfere with an individual’s Fifth and Fourteenth Amendment liberty interests and freedom of bodily movement. They are arrests, after all; the root word means to “stop” someone from doing something. Arrests are restraints upon the individual which cause more serious consequences than mere fines, confiscations of property, or harms to reputation through edicts, judgments, or reprimands. That is why the statutes of a number of states explicitly require that information pertaining to arrests be made available to the public.

Under California state statute, law enforcement agencies are required to disclose to the public most information pertaining to an arrest. Among the data which must legally be released, according to the statute, is the following:

The full name and occupation of every individual arrested by the agency, the individual’s physical description including date of birth, color of eyes and hair, sex, height and weight, the time and date of arrest, the time and date of booking, the location of the arrest, the factual circumstances surrounding the arrest, the amount of bail set, the time and manner of release or the location where the individual is currently being held, and all charges the individual is being held upon, including any outstanding warrants from other jurisdictions and parole or probation holds.

The statute does contain some exceptions which allow law enforcement agencies to withhold information that “would endanger the safety of a person involved in an investigation or would endanger the successful completion of the investigation or a related investigation.” A few other specific restrictions allow the authorities to withhold some information on the curtilage of an arrest, e.g., to protect the identities of crime victims. But, generally, the core arrest information itself is public.

The government cannot legally make secret arrests. The concept has been hashed and re-hashed in countless court cases, including Morrow v. District of Columbia, 417 F.2d 728, 741-42 (D.C. Cir. 1969) (stating that “arrest books” must be “kept public” to “protect[] against secret arrests,” because secret arrests would be “odious to a democratic society”), Dayton Newspapers, Inc. v. City of Dayton, 45 Ohio St.2d 107, 112 (1976) (holding that a jail log is not kept merely for the “convenience of the jailer” but rather must be kept for public inspection), and Houston Chronicle Publishing Co. v. City of Houston, 531 S.W.2d 177 (Tex. App. 1975) (holding that a plethora of police documents “are public records available to the press and public” and “should be made immediately available at a convenient central location to meet the need of the public’s right to know”). Elsewhere, courts have held that actual charges (not just the fact of an arrest) must be made public. Newspapers, Inc. v. Breier, 279 NW 2d 179 (Wis. 1979). And, the U.S. Supreme Court long ago ruled that defendants cannot sue police departments for publicizing their arrests. Paul v. Davis, 424 U.S. 693 (1976). Even the names of the Guantanamo Bay detainees are public. The Department of Defense released the names after a federal judge ordered that the detentions not remain fully secret.

The Journalistic Process

Most journalists know this, and even small town newspaper reporters who earn $18,000 a year for full-time labor are adept at using the law to their advantage to obtain and to publish the daily local police blotter. So, it is rather easy to confirm that Schiff has, indeed, not been arrested.

First, Schiff’s name does not and did not appear on the actual, official list of people incarcerated by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department as maintained by the department itself. Additionally, in response to social media links and Twitter screenshots provided by Law&Crime, Lt. John Satterfield of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Information Bureau told Law&Crime via email that the “Bureau is unaware of any recent law enforcement contact at LAX involving the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and U.S. Representative Adam Schiff.”

Second, the Los Angeles Police Department’s Media Relations Division, when reached by telephone by Law&Crime, said that they had “no information” to suggest that Schiff had contact with the department. The LAPD reiterated that something that important would have immediately passed through the chain of command and disseminated.

Third, a spokeswoman with the FBI’s Los Angeles Field Office tells Law&Crime that she was “unaware of such an arrest by the FBI.”

Fourth, Schiff’s office told Law&Crime in response to an email inquiry that the online suggestions that the congressman was arrested or questioned by the authorities are “flagrantly false.”

Fifth, just for fun, Law&Crime contacted two spokespeople for the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Central District of California. They did not return emails seeking comment, but sources close to that office tell Law&Crime that the office is also unaware of any such case.

Experienced professional journalists also know that big arrests are not ‘secret’ for very long. Local departments are notoriously (and sometimes problematically) loose-lipped. While the FBI is generally not, when the federal government does go after a high-profile person of interest or target, an arrest is generally announced immediately and through official channels. For instance, when several famous people were arrested in the so-called “Operation Varsity Blues” college cheating scandal, federal officials sent out press releases and even held a press conference to announce the fruits of their labor pursuant to their legal obligations to not make secret arrests. Such matters are generally handled carefully yet candidly.

Reporters might not always obtain video of a high-profile arrestee being hauled to jail, and they might not necessarily be given booking photos because of an arresting agency’s policy or nuances in state laws, but they will under every imaginable circumstance be given—either without asking or after asking—official documentation that an arrest did, indeed, occur. Later, under other laws, journalists will obtain government documentation that an actual legal proceeding has commenced via the filing of a complaint. Or, if a case has not been commenced, journalists are readily able to ascertain that a prosecution has been declined or an investigation has been declared inactive. Only rarely are court records sealed, and sometimes sealed records are opened pursuant to litigation by media or transparency groups.

It is not news that we are witnessing the financial decline of professional journalism and the information chaos which ensues when everyday people try to undertake the collective task of ferreting information from sources with which they may be unfamiliar through processes they have not previously studied or used. Sometimes, that results in relevant information being archived against deletion and rendered public more quickly than ever, but sometimes it results in the widespread transmission of flat out lies.

There is no conspiracy here: Schiff simply wasn’t arrested, and the laws which compelled the official statements and the lack of credible documentation prove it. To assume otherwise is illogical. As founding father Thomas Jefferson said (emphasis ours):

If a nation expects to be ignorant and free in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be. The functionaries of every government have propensities to command at will the liberty and property of their constituents. There is no safe deposit for these but with the people themselves, nor can they be safe with them without information. Where the press is free and every man able to read, all is safe.

The only information professional journalists hide is information (1) that is given off the record, or (2) information that cannot be confirmed. Even the most die-hard partisan left-leaning journalist on the planet would still report a high-profile liberal politician’s arrest. Like all employees, journalists have a legal duty of faithfulness to serve the interests of their employers. Any news agency and every independent journalist would be happy to publicly report such an arrest and to reap the profits for so doing.

[Image via Drew Angerer/Getty Images]