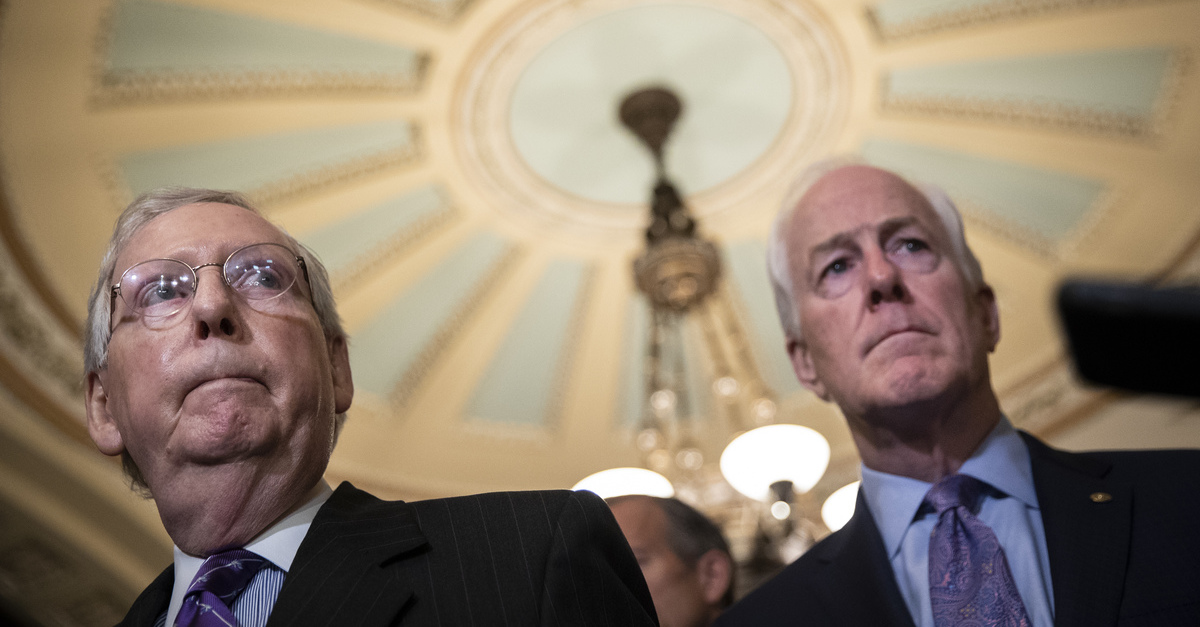

The Coronavirus (COVID-19) rescue bill proposed by Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) contains a controversial liability shield that would limit the ability of employees to sue their employers for contracting COVID-19 while on the job. Congressional Democrats have publicly dismissed the would-be shield law as a non-starter. Congressional Republicans were apparently just getting started.

The relevant portion of the GOP relief bill is known as the “Safeguarding America’s Frontline Employees To Offer Work Opportunities Required to Kickstart the Economy Act’’ (SAFE TO WORK Act) and was authored by Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas).

In general, critics say the SAFE TO WORK Act is likely to do the opposite of making workplaces safer because it attempts to dismantle tort liability. Liability is widely understood to be a form of market pressure that forces those who may be held liable (here, employers) to take proactive safety measures.

Many of the federal provisions appear to have been copied word-for-word from New York Governor Andrew Cuomo‘s own liability shield protections for nursing homes and hospitals that were inserted into the Empire State’s recent budget. (That budget was passed as Cuomo oversaw large COVID-19 death tolls in his state.)

Another portion of the bill, however, takes the long-clamored-for business lobby goal of liability protection one step further by creating a private right of action for businesses who even receive demand letters from potential plaintiff employees.

Demand letters are fairly self-explanatory letters which outline a party’s alleged injuries and what they would like to receive. They are typically–though not always–preludes to an actual lawsuit and, in such situations, often contain lawsuit threats.

Per the proposed Cornyn law:

SEC. 164. DEMAND LETTERS; CAUSE OF ACTION.

(a) CAUSE OF ACTION.— If any person transmits or causes another to transmit in any form and by any means a demand for remuneration in exchange for settling, re-leasing, waiving, or otherwise not pursuing a claim that is, or could be, brought as part of a coronavirus-related action, the party receiving such a demand shall have a cause of action for the recovery of damages occasioned by such demand and for declaratory judgment in accordance with chapter 151 of title 28, United States Code, if the claim for which the letter was transmitted was meritless.

The rub here is that the end goal of the SAFE TO WORK Act is to make sure that most liability claims are, as the proposed legislation itself says, “meritless.”

The preamble to the bill references the alleged lack of merit in potential liability claims brought by workers against allegedly negligent employers.

“These lawsuits pose a substantial risk to interstate commerce because they threaten to keep small and large businesses, schools, colleges and universities, religious, philanthropic and other nonprofit institutions, and local government agencies from re-opening for fear of expensive litigation that might prove to be meritless,” one section claims.

The proposal also outright says its “purpose is” to “protect interstate commerce from the burdens of potentially meritless litigation.”

The Cornyn-McConnell legislation also gives the attorney general wide latitude to commence “civil action in any appropriate district court” related to Coronavirus-themed demand letters.

And the potential downside loss for anyone sending such a demand letter, which the bill says would include both the prospective plaintiffs and their theoretical attorneys, is huge.

Again, the Cornyn language:

In a civil action under [the demand letter section], the court may, to vindicate the public interest, assess a civil penalty against the respondent in an amount not exceeding $50,000 per transmitted demand for remuneration in exchange for settling, releasing, waiving or otherwise not pursuing a claim that is meritless.

The proposed legislation naturally has its critics among those who represent individual employees.

“Defending the right of employers to unreasonably endanger their employees’ health without consequences is an interesting hill to die on,” mused administrative law expert Sasha Samberg-Champion.

[image via Drew Angerer/Getty Images]