Nijeer Parks, a 33-year-old Black man, is suing a New Jersey city, police department, and prosecutor for false arrest, false imprisonment and violation of his civil rights for misidentifying him using facial recognition software.

In Jan. 2019, police officers responded to a call at a Hampton Inn in Woodbridge, New Jersey. A Black man had reportedly shoplifted candy from the gift shop. When the police arrived, they encountered the man in question, who presented them with a fake driver’s license. One officer spotted a bag of marijuana in the man’s pocket, and when the officers tried to handcuff him, the man ran away. He lost a shoe before departing in a rental car.

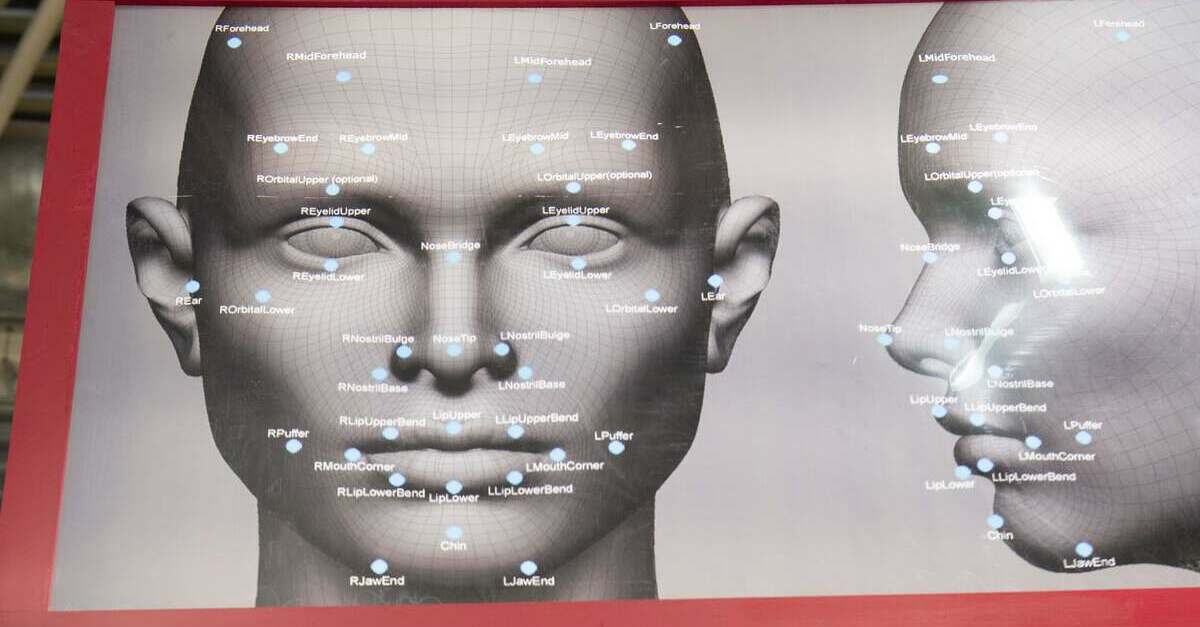

The man drove away, but not before hitting a parked police car and column in front of the hotel, and almost hitting one of the officers. The car was later found abandoned. The police sent the photo from the man’s fake ID for processing through facial-recognition software, and the search yielded a name: Nijeer Parks. A warrant was issued for Parks’ arrest.

Parks, however, never had a driver’s license, never owned or rented a car, and had never been to Woodbridge. He had also been 30 miles away at the time of the incident and had an alibi for those whereabouts. According to his complaint, Parks heard about the warrant from his grandmother and contacted the Woodbridge Police Department to clear things up. According to Parks, he knew the case was one of mistaken identity. The facial recognition software had misidentified Parks.

When Parks called and later met with police, though, the mistake was not rectified. Instead, police interrogated Parks.

According to the complaint, “As the interrogation got more intense and hostile, the police investigators tried to have [Parks] moved to a room in the back of the police offices out of range of the camera causing [Parks] to fear that he was going to be tortured.”

That’s when things went out of control. According to Park’s account he feigned an asthmatic attack and fell to the ground “in order to avoid torture.” EMS was called, and Parks “managed to avoid being beaten at the police headquarters.” However, after he was examined by EMS, Parks was processed and transferred to county jail. He was arrested, denied bail, and held for 10 days at the Middlesex County Corrections Center.

For all that time, Parks was put in what his complaint called “functional solitary confinement,” because he was kept on “intake” status. He ate alone, was denied recreational time with others, and time outside. What’s more, Parks alleges that “While wrong [sic] kept in intake for an extended period, Plaintiff was in fear of physical abuse as the Corrections Officers verbally threatened him with excessive force because, they wrongly asserted, he had attacked a fellow officer.”

Eventually, Parks was released from jail, but, as he argues in his complaint, law enforcement “kept [Parks] in a state of apprehension for a year, refusing to drop charges, demanding a plea to lesser included charges, and promising that he would be tried and convicted.” Parks hired a lawyer, and remained “terrified that some inexplicable conspiracy or vendetta would destroy him” while he awaited his fate. In Nov. 2019, the case against Parks was dismissed for lack of evidence.

The consequences endured by Parks were extreme: he suffered not only emotional hardship, but financial damage and job loss. Perhaps even more disturbing, Parks told the New York Times that because he’d had past experiences with the criminal justice system, he seriously considered taking a plea deal in the case despite his innocence.

Parks is the third person known to be falsely arrested based on a faulty facial recognition technology. The other two people —Robert Williams and Michael Oliver — are also Black men. Civil rights advocates denounce the use of facial recognition software, pointing to its tendency to disproportionately misidentify Black men.

Parks’ complaint alleges that the police department “was relying solely on the faulty and illegal Clearview Facial Recognition App or some analogous program while all evidence and forensics confirmed that Plaintiff had no relationship to the suspect for the crimes.”

Reportedly, however, Park’s attorney, Daniel Sexton, used the name “Clearview” in the complaint as a generic term for facial recognition software used by police.

There may be reason to believe that the actual software used was not, in fact, produced by Clearview.

Whatever the exact software used in Parks’ case, one thing is clear: as law enforcement increasingly relies on facial-recognition technology for arrests, both lawsuits and legislation are likely to follow.

Law&Crime could not immediately reach an attorney for Mr. Parks for comment.

[Photo by image via Nicolas Asfouri/AFP via Getty Images]