You know you’ve got a serious criminal on your hands when Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme, the former sidekick of mass murderer Charles Manson and aspiring presidential assassinator, admits to being intimidated by them in their shared federal prison. Yet, that’s exactly the kind of impact Ana Montes made on those around her after her decades-long stint as a double agent for Cuba and the United States crumbled in the early 2000s.

To quote Fromme’s impression of Montes,

“She is the least talkative person that I probably ever met. She is the most taciturn person…She wasn’t trying to ingratiate herself nor was she trying to be tough.”

Like any good spy, knowing anything about who Ana Montes is – or what she’s thinking – seems to be an impossible task.

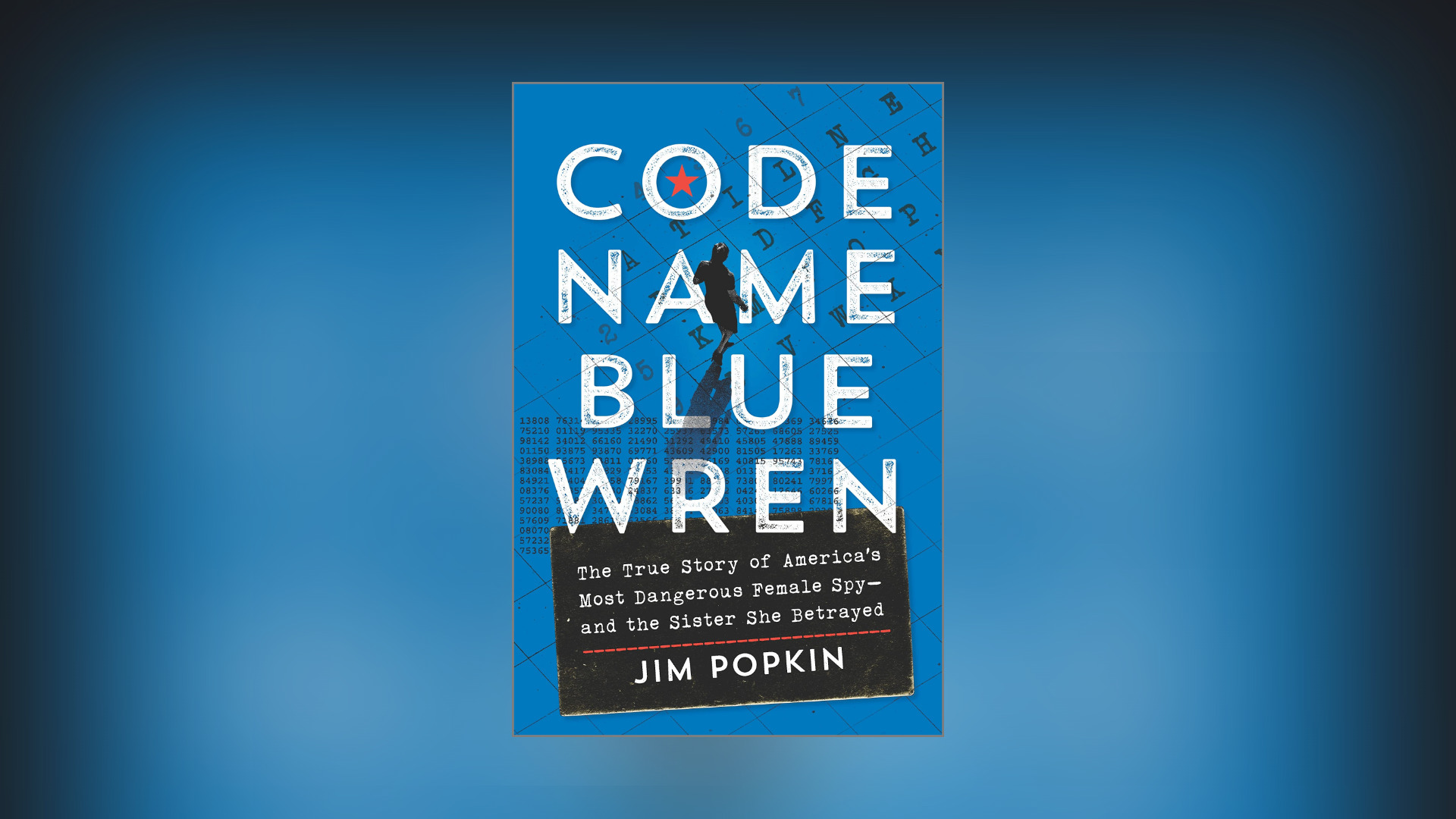

Still, it’s this impossible task of spy profiling that author Jim Popkin undertakes in his new book Code Name Blue Wren: The True Story of America’s Most Dangerous Female Spy – and the Sister She Betrayed. Having followed the story as a reporter since its break – only a few short days after 9/11 – he is not only expertly familiar with Montes’ background and political radicalization, but he understands more than anyone else in the media world why the story stayed mostly out of the headlines for so long. As Popkin makes apparent, revealing what doesn’t make the headlines is often more telling than rehashing what does.

Similarly, what makes a spy story in general so compelling is the spy’s utter unknowability. The mystery of their identity is often far more engaging than any of the political dramas and catastrophes going on around them. We, as readers, keep reading because we are struck by an intense need to peel the mask off of these most elusive characters and resolve the mystery that is their journey towards becoming who they are. But as Popkin tells it, the figure of the disgraced spy is actually far more complex than just narrative tropes for us to project our own political beliefs onto, as we are often led to believe.

What Popkin smartly hones in on is the heartbreak of the whole Montes family, in particular her sister Lucy who she worked alongside at the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) on Cuba relations for many years . Hiding your beliefs and actions from your military coworkers is one thing, but keeping them from the very people with whom you’ve shared a household and an upbringing with is uniquely shocking.

The Montes family was a well-known one in the 1980s and 90s, praised for their high achievements in academia, medicine and the US military – which makes the treasonous choices of one of their closest kin that much tougher to swallow. Popkin’s decision to chronicle their reactions and their unraveling at the arrest, trial and imprisonment of their beloved sister and daughter is an impactful one that ultimately leaves Code Name Blue Wren overflowing with often overlooked perspectives, emotional appeals and glimpses into a demonized turncoat’s more sympathetic side while still regarding her with fear and criticism.

Popkin fills his account with quotes from Lucy enumerating Ana’s wrongdoings and tearing apart any possible rationalizations. She slams her sister again and again, labeling her as a coward who betrayed those who loved her most in order to sell her beliefs to an evil power. Yet he ends Code Name Blue Wren with the image of a woman contemplating the possibility of taking her now destitute sister back into her home upon her release from prison.

In his epilogue, Popkin reveals his fascination with the Montes affair to be slightly personal in nature, describing how she took it upon herself to mock a profile he wrote on her for Washington Post Magazine in 2013. Assuming the tone of media critic, Montes wrote in a letter from prison that the profile was not hard-hitting journalism at all, but rather “better suited to People Magazine given the article’s focus on personality and the ‘diametrically opposite’ way Lucy and Ana conducted their lives”.

Ana, still firm in her anti-American stance even in the middle of serving her sentence for espionage, lashed out against the inclusion of misleading analysis of her motivations when really it should have been America’s sins in Latin America under scrutiny. In reading the story of her own downfall, she wanted hard facts, not stories that meander into realms of personal responsibility and behavioral psychology. Most hard criminals beg for these sorts of sympathetic characterizations, but for Ana it’s just a distraction from the cause.

Popkin’s decision to include this anecdote for the reader to chuckle at – after spending 300 pages illuminating the horrors of such a massive personal and national betrayal – is a small yet risky and crucial one. Including Ana’s own opinions on how her story is told is still arguably the most impactful detail of the entire book. It clarifies Popkin’s intentions to tell a story that goes beyond the typical spy narrative, jam-packed as they usually are with high-stakes action and political danger but absent of any sense of relatability. It also centers Ana’s relationship with her sister, Lucy, as the actual tension in the story.

What, after all, are the tangled political relations between a fascist regime and its imperialist counterpart compared to a lifetime of tense, unbridgeable relations between two sisters?