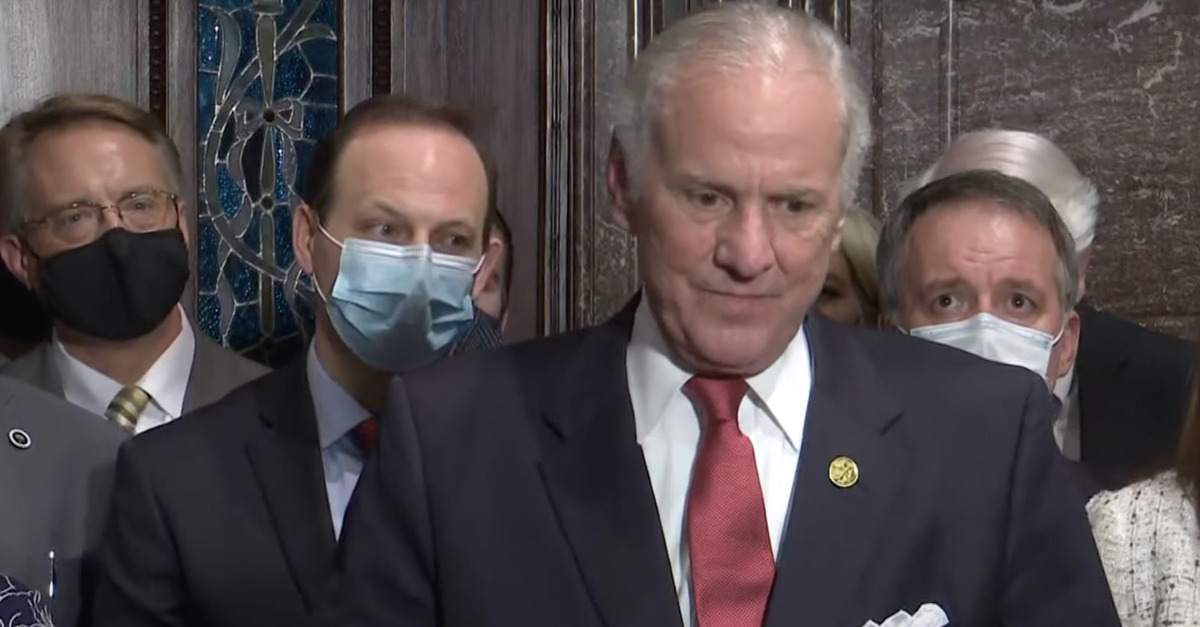

South Carolina Gov. Henry McMaster (R) discusses signing the Fetal Heartbeat and Protection from Abortion Act into law.

In a 3-2 ruling, the South Carolina Supreme Court struck down the state’s restrictive abortion law Thursday, making the Palmetto State’s judiciary the first top state court to throw out a post-Dobbs abortion ban.

The law at issue, South Carolina’s Fetal Heartbeat and Protection from Abortion Act, bans all abortions after cardiac activity is detected, which is typically round six weeks of gestation. The measure was signed into law in February 2021 by South Carolina Gov. Henry McMaster (R). Since then, it’s been the subject of both federal and state level challenges in court.

After the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade last June, though, the law’s permissibility under the U.S. Constitution was essentially a foregone conclusion. However, South Carolina’s top court — the ultimate interpreter of the state’s constitution— clarified that under South Carolina law, abortion standards are remarkably different.

Justice Kaye Hearn explained in a 24-page opinion that it all comes down to privacy – which South Carolina guarantees even if the federal government does not.

Unlike the U.S. Constitution (which never specifically mentions “privacy”), Article I, § 10 of the South Carolina Constitution states, “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures and unreasonable invasions of privacy shall not be violated…”

Accordingly, Hearn said that the Supreme Court’s ruling in Dobbs “does not control, nor even shed light on” the question before the South Carolina court, because “Roe was overturned partially based on its reliance on an unmentioned and hence arguably nonexistent constitutional right to privacy,” while “the South Carolina Constitution expressly includes a right to privacy.”

Hearn wrote:

We hold that the decision to terminate a pregnancy rests upon the utmost personal and private considerations imaginable, and implicates a woman’s right to privacy. While this right is not absolute, and must be balanced against the State’s interest in protecting unborn life, this Act, which severely limits—and in many instances completely forecloses—abortion, is an unreasonable restriction upon a woman’s right to privacy and is therefore unconstitutional.

Chief Justice of the South Carolina Supreme Court Donald Beatty penned a separate concurrence, emphasizing the importance of privacy under state law:

Privacy has no meaning if we fail to limit how closely the state may regulate our personal, medical, intimate, and moral decisions. While all agree our government generally cannot search our homes—the pinnacle of privacy—without a warrant, the outer bounds of privacy are still debated.

In a passage dripping with irony, Beatty quoted the U.S. Supreme Court’s own words from the high court’s 1972 ruling in Eisenstadt v. Baird:

Today, we recognize the true breadth of this fundamental right, which all South Carolinians enjoy: “If the right of privacy means anything, it is the right of the individual, married or single, to be free from unwarranted governmental intrusion into matters so fundamentally affecting a person as the decision whether to bear or beget a child.”

Beatty also provided lengthy analysis in which he concluded that South Carolina’s restrictive abortion law violates the state’s constitution “beyond a reasonable doubt,” in that it offends guarantees of equal protection and denies both procedural and substantive guarantees of due process.

Justice John Cannon Few also penned a concurrence in which he discussed the scope of South Carolina privacy rights at length. Few said that the mere existence of privacy interests “does not give rise to a ‘right’ to abortion,” but rather, that abortion laws like many other laws must avoid “unreasonable invasions on privacy.” South Carolina’s abortion ban was just such an “unreasonable invasion,” said the justice — though he qualified that in general, “The extent to which abortion should be regulated is a legislative—or political— question.”

Justices John Kittredge dissented, and called the term “privacy” in the state constitution “ambiguous.” Kittredge said he would defer to the state legislature, which passed the act based facts it gathered during the legislative process. He wrote:

Scientific knowledge, of course, has increased significantly through the years, for medical knowledge now establishes “evidences of life” early on in the pregnancy. The detection of a fetal heartbeat approximately six to eight weeks into the pregnancy is an example. That is the precise kind of information considered in the legislative fact-finding process that was relied on in crafting the Act.

By contrast, Kittredge slammed the majority for making its own findings. Kittredge called the majority, saying: “It is breathtaking that members of this Court would unilaterally do their own factfinding and cite to ‘evidence’ outside the record in an effort to bolster their desired result.”

Justice George James also penned a dissent in which he said that while would have upheld the law, he differed from Kittredge as to the analytical framework that applied. James also said that he would acknowledge the guarantee of privacy under the South Carolina constitution, but that in his opinion, the guarantee only applies in the context of searches and seizures.

White House Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre immediately reacted to the court’s ruling in a tweet saying, “We are encouraged by South Carolina’s Supreme Court ruling today on the state’s extreme and dangerous abortion ban. Women should be able to make their own decisions about their bodies.”

Gov. McMaster reacted to the ruling Thursday in a tweet in which he said the court “clearly exceeded its authority.” “Our State Supreme Court has found a right in our Constitution which was never intended by the people of South Carolina,” the governor continued.

[screengrab via YouTube/WLTX]