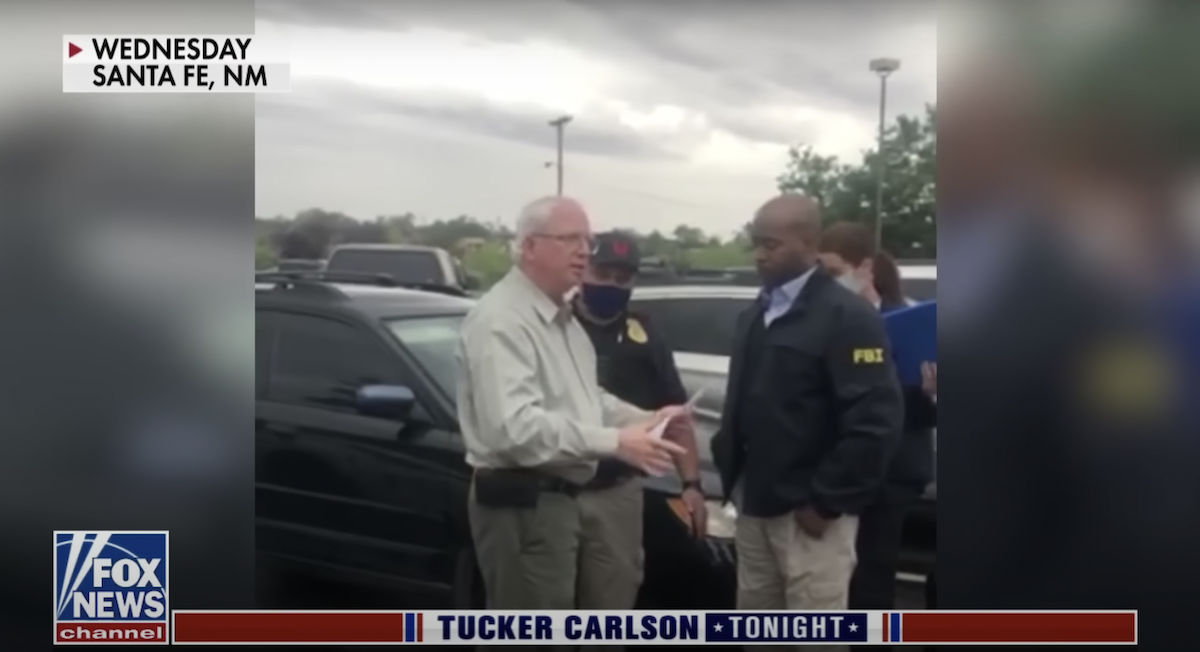

In a June 28, 2022, appearance on Tucker Carlson Tonight on Fox News, John Eastman shared video of himself being searched by federal agents on June 22 in New Mexico. (screenshot from YouTube)

Prosecutors say that a federal agent “obtained a second federal search warrant” for the cell phone of Donald Trump’s attorney John Eastman, who hatched a six-part plan to overturn the 2020 election that is now the subject of an investigation.

In June, Eastman filed a federal lawsuit in New Mexico demanding the return of his cell phone after vividly describing the search the preceded it. The lawyer, sometimes described as Trump’s “coup memo” author, said FBI agents frisked him as he exited a restaurant, seized his iPhone Pro 12 and forced him to provide biometric data to open it.

A federal judge rejected Eastman’s variety of constitutional objections to search earlier this month, writing that he “was relying to a considerable extent on the assertion in the warrant that the investigative team will not examine the contents of the phone until it seeks a second warrant.”

In a filing on Wednesday, federal prosecutors confirmed they’d done so – three days before Senior U.S. District Judge Robert C. Brack’s July 15 order that they tell him by July 27 where the phone is and whether they’d applied for a second warrant. Prosecutors waited until Wednesday’s deadline to disclose that they had.

“On July 12, 2022, a federal agent obtained a second federal search warrant from the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia that authorizes review of the contents of Plaintiff’s cell phone and the manual screen capture,” it states. “The warrant includes a filter protocol, which has been provided to Plaintiff’s counsel.”

A filter team, formally titled a privilege-review team and sometimes known as a taint team, provides a firewall within the Department of Justice preventing prosecutors assigned to an investigation from reviewing files that may be privileged, as Eastman is an attorney. Instead, the material is reviewed by a separate set of DOJ employees who then provide relevant material to case prosecutors.

In January, Eastman’s asserted attorney-client and work product privileges to try to stop his former employer Chapman University from disclosing tens of thousands of pages of emails and documents from his university email account to the Jan. 6 Committee.

U.S. District Judge David O. Carter in Santa Ana, California, gave him a huge early win, halting the release and instigating a weeks-long review in which the judge acted as the final arbitrator on what went to the committee.

But in two separate ensuing orders, Carter determined two key documents that were legally covered by attorney-client privilege review should still be released to the committee because they were written in furtherance of crimes the judge said Eastman and Trump likely committed, obstruction of an official proceeding and conspiracy to defraud the United States.

The orders attracted widespread attention, particularly the first on March 28, in which Carter called Trump and Eastman’s actions “a coup in search of a legal theory” and said he feared another Jan. 6 “if the country does not commit to investigating and pursuing accountability for those responsible.” His order on June 7 and the ensuing release of the emails also revealed Eastman’s communications with Ginni Thomas, wife of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, whose name Carter ordered to remain unredacted.

But Carter’s orders also overall endorsed Eastman’s arguments that his materials are subject to attorney-client privilege, even materials that Chapman officials claimed were the university’s property and fine to disclose in full to the committee. He withheld hundreds of emails from the committee, and on June 11, after a request from Eastman, the judge protected 10 emails he’d previously ordered released, acknowledging that he mistakenly classified them as unassociated with legitimate legal work. And while he applied the crime-fraud exception in both orders, the judge also declined to apply it to others.

Eastman cited Carter’s process in his motion last month in the District of New Mexico, with his lawyers writing that the court “expressly determined that a number of movant’s emails—emails which are accessible through movant’s cell phone—are protected by the First Amendment’s freedom of association, by attorney-client privilege, and/or by the work product doctrine.”

“The California district court also found that hundreds of movant’s emails—also accessible by the seized phone—are protected by attorney-client privilege and/or the work product doctrine,” according to the motion.

However, as Judge Brack identified in his July 15 rejection of Eastman’s TRO request, the U.S Department of Justice has a well-known process for reviewing possibly privileged documents. While U.S. House Counsel Douglas Letter declined to tell Carter in January if the Jan. 6 Committee had considered such a process for Eastman’s emails, Brack, observed in the New Mexico case that Eastman “makes no argument that the Government will not provide for an appropriate review of privileged documents.”

“The parties may further explore this issue in briefing on the motion for preliminary injunction,” Brack wrote.

The DOJ’s response to Eastman’s motion is due Aug. 8, with Eastman’s option reply due two weeks after the opposition is filed. A hearing is scheduled before Brack in Albuquerque.

Eastman’s June 27 motion was the first confirmation hat his phone had been seized in a federal criminal investigation, which he said occurred June 22 as he stepping outside a restaurant in Albuquerque with his wife. He challenged the warrant, in part, because the FBI executed it “at the behest of the Department of Justice’s Office of the Inspector General,” and he was never the agency’s employee.

Prosecutors have noted, however, that Eastman’s plan called for Justice Department involvement.

“The United States is in possession of Plaintiff’s cell phone, as well as a manual screen capture of certain contents of the device obtained by an agent not associated with the investigation team,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Thomas P. Windom wrote in a two-page filing. “Plaintiff’s cell phone and the manual screen capture currently are in Northern Virginia, in the possession of federal agents with the Department of Justice, Office of Inspector General.”

Former federal prosecutor Mitchell Epner, now a partner at Rottenberg Lipman Rich PC, told Law&Crime that it isn’t quite surprising that the government succeeded in obtaining a warrant to scrutinize the phone after securing one to seize it.

Nevertheless, Epner said, the development is significant.

“What it does say is that on two separate occasions, a United States magistrate judge or United States district judge reviewed an affidavit from the Office of the Inspector General, and concluded two separate and equally important things: number one, that there was probable cause to believe that a felony had been committed, and number two, that there was probable cause to believe that evidence of that felony could be found on that phone,” he said.

Read the DOJ’s filing, below:

(Image: Screenshot from Fox News on YouTube)

(Photo by MANDEL NGAN/AFP via Getty Images)